Income inequality in the U.S. has grown rapidly over the past thirty years, but almost no research has found that shifts in government policy led to greater inequality and the associated stagnation in middle incomes. In new research, David Jacobs finds evidence of the role of politics in determining inequality, by analyzing union strength. He finds that prior to the election of President Ronald Reagan, a 10 percent increase in union strength would have led to a 2.7 percent fall in income inequality, but this union effect disappears after 1981. His results show that Reagan and subsequent neoliberal presidents, including Democrat Bill Clinton, contributed to the growth in inequality by continuing to attack unions and deregulating financial markets.

Income inequality in the U.S. has grown rapidly over the past thirty years, but almost no research has found that shifts in government policy led to greater inequality and the associated stagnation in middle incomes. In new research, David Jacobs finds evidence of the role of politics in determining inequality, by analyzing union strength. He finds that prior to the election of President Ronald Reagan, a 10 percent increase in union strength would have led to a 2.7 percent fall in income inequality, but this union effect disappears after 1981. His results show that Reagan and subsequent neoliberal presidents, including Democrat Bill Clinton, contributed to the growth in inequality by continuing to attack unions and deregulating financial markets.

“It is our job to glory in inequality and to see that talents and abilities are given vent and expression for the benefit of us all.” – Margaret Thatcher

“A quick glance at the curves describing wealth inequality or the capital/income ratio is enough to show that politics is ubiquitous and that economics and political changes are inextricably intertwined and must be studied together.” – Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, p. 577

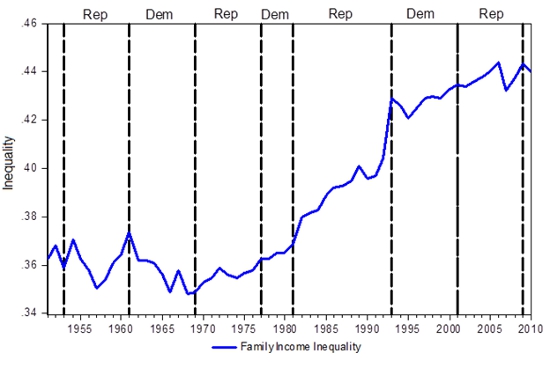

What factors best explain the remarkable expansion in U.S. income inequality? In a striking reversal in the long trend toward greater economic equality in the affluent democracies since 1900, the differences in U.S. family incomes accelerated sharply after 1980 (see Figure 1) after experiencing only modest growth. This departure, although present in other wealthy democracies, has been less pronounced elsewhere. Yet as the quotes above suggest, it is difficult to believe that politics did not have a major influence on the rapid increase in income inequality after 1980. To date, however, little systematic evidence for such a claim has been available. Yet political accounts are likely to matter more in some periods as governmental control shifts from one political party to another.

Figure 1 – Fluctuations in U.S. Income Inequality, 1951 – 2011

Note: Larger values denote greater inequality; vertical lines denote partisan shifts in the Presidency and “Rep” stands for Republican while “Dem” stands for Democratic Presidents.

With these assumptions in mind, Lindsey Myers and I conducted a longitudinal analysis of the factors that produced yearly changes in family income inequality from 1951 to 2010. We find that the steep decline in union strength and deregulation of the financial industry that occurred after Ronald Reagan’s presidency began in 1981 has contributed to the stagnation of middle incomes and the rise of income inequality.

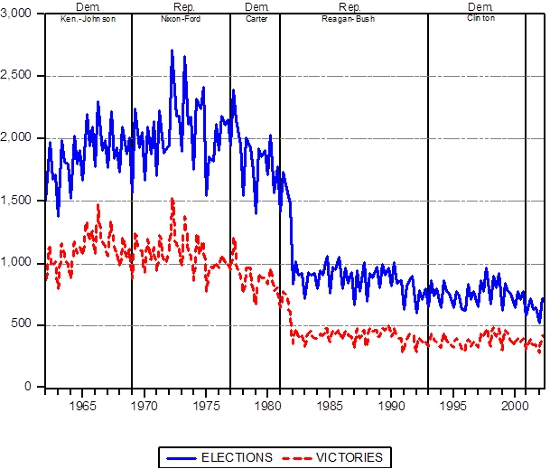

One determinant of income inequality that is highly dependent on political decisions is union strength. In a prior study, Daniel Tope and I analyzed changes in union recognition elections that determine if a U.S. work place will be unionized. We found that soon after Ronald Reagan became president, a precipitous decline occurred in these elections (see Figure 2)—which are regulated by the National Labor Relations Board, under close presidential control. Why would union strength measured by the percentage of union members matter? Stronger unions decrease the differences in earnings within firms. And before the politically induced steep decline in union strength that began in 1981, unions probably were the most effective pressure group that lobbied for policies helpful to less economically fortunate U.S. citizens.

Figure 2 – Number of Union Recognition Elections and Union Victories, 1962 – 2001

Note: Vertical lines denote partisan shifts in the presidency

In light of President Reagan’s aversion to unions and his distaste for political attempts to protect less prosperous citizens from destructive labor market changes, we suspected that we would find evidence for two conditional political relationships. First, increased union strength before Reagan’s presidency should reduce income inequality after adjusting for other determinants, but union strength should not matter during and after the Reagan administration’s tenure because the then politically weakened unions no longer had much political influence.

Second, Reagan’s resolute anti-union stance was partly based on sympathy for policies that advantaged his political party’s affluent base. These citizens wish to avoid higher taxes and often profit from cheap labor. For example, findings show that tax policies most helpful to the prosperous—that at least indirectly increased tax burdens on other citizens—became increasingly likely after Republican presidents took office. Republican macroeconomic policies also favored the affluent by stressing curbs on inflation at the expense of higher unemployment. Such predilections enhanced the economic distance between the least affluent—who suffer more from joblessness—and their more fortunate counterparts. Because the Reagan neoliberal departure—which was endorsed by subsequent Republican presidents—increased the economic and political resources of business and the affluent, we expected to find that the presence of Republican administrations during and after Reagan’s presidency would produce additional increases in family income inequality.

Our results support both hypotheses. After many competing explanations are taken into account, our findings suggest that in the period before Reagan’s presidency, a 10 percent increase in union strength would have produced about a 2.7 percent decrease in income inequality. Yet during and after Reagan’s tenure, because he and subsequent neoliberal presidents decreased union strength, fluctuations in this strength had no effect on inequality. And again after adjusting for many plausible accounts, our findings show that a shift to a post 1980 Republican president increased income inequality by about 3 percent.

A somewhat surprising result concerns President Clinton’s policies, which also enhanced inequality. Although Clinton was a Democrat and this party is less sympathetic to neoliberal market solutions than Republicans, Clinton was exceptional. Immediately before his presidency Clinton chaired the Democratic Leadership Council. This association was dominated by “New Democrats” who opposed collective bargaining and other center left policies. As president Clinton endorsed globalization by signing into law the NAFTA free trade agreement between the U.S., Canada and Mexico. Clinton also supported a change to a neoliberal market driven welfare system and he further deregulated the financial industry.

The deregulation of the financial sector proved to be influential. Sociological studies show that many firms—which before had specialized in other economic activities—began to reap significant profits from purely financial undertakings. This change occurred shortly before and during the great acceleration in economic inequality after 1980 partly because such activities were deregulated by Reagan appointees and by subsequent neoliberal administrations. Our findings and others suggest this deregulation produced greater economic inequality probably because it let financial specialists negotiate substantial increases in their compensation.

But our results do not corroborate other plausible accounts. Despite almost universal support within the economics profession, we find no evidence that a growth in the proportion of adults with four or more years of college created subsequent increases in inequality, but these negligible findings may be attributable to measurement problems. Other popular accounts that do not explain the sharp post 1980 growth in U.S. inequality include increases in globalization and international trade, the growth in women’s employment, and employment shifts into services or away from manufacturing.

In short, our findings suggest that the politically induced reduction in union strength helped produce stagnation in the incomes of those near to or below the middle of the income distribution during times when most prosperous family incomes accelerated rapidly. These events occurred when political deregulation of finance also contributed to the post 1980 acceleration in U.S. income inequality probably by increasing the ability of financial specialists to bargain for higher pay. Our investigation clearly suggests that the substantial acceleration in U.S. income inequality after 1980 is at least partially attributable to politics.

This article is based on the paper “Union Strength, Neoliberalism, and Inequality: Contingent Political Analyses of U.S. Income Differences since 1950” in the American Sociological Review.

Featured image credit: Lord Jim (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1poBh64

______________________

David Jacobs – The Ohio State University

David Jacobs – The Ohio State University

David Jacobs is Professor Emeritus of Sociology at The Ohio State University. His research mostly involves studies in political sociology using a political economic perspective applied to issues such as labor relations and criminal justice outcomes like the use of the death penalty.

4 Comments