What drives criminal justice policy in America? Using data from a study of criminal justice policy from 2002 to 2007, Katharine A. Neill finds that criminal justice policy is complex and multidimensional, with many factors influencing policies. For example, states with more violent crime are more likely to arrest people for ‘immorality’ crimes, such as drug abuse and prostitution, and those with higher rates of property crime tend to have less punitive incarceration practices. She also finds that states with larger Black populations are also more likely to have more punitive incarceration practices, conditions of confinement and juvenile justice policies.

What drives criminal justice policy in America? Using data from a study of criminal justice policy from 2002 to 2007, Katharine A. Neill finds that criminal justice policy is complex and multidimensional, with many factors influencing policies. For example, states with more violent crime are more likely to arrest people for ‘immorality’ crimes, such as drug abuse and prostitution, and those with higher rates of property crime tend to have less punitive incarceration practices. She also finds that states with larger Black populations are also more likely to have more punitive incarceration practices, conditions of confinement and juvenile justice policies.

The criminal justice system includes many moving parts: laws written by legislators; enforcement of those laws by police, prosecutors, and judges; containment of convicted lawbreakers in jails and prisons; oversight of ex-offenders by probation and parole officers; and separate treatment of juvenile and adult offenders. In recent research that examines criminal justice policy practices in the United States, my colleagues and I find that while all these actions operate under the broad criminal justice umbrella, they occur in realms governed by different sets of policies that are themselves shaped by different sets of factors.

When people in the U.S. break the law, they are more likely to go to prison than they would be in other countries. Currently, the U.S. incarceration rate is 707 per 100,000 people, the largest in any country except Seychelles, an island nation off the coast of Africa. High incarceration rates have earned America a reputation as a particularly punitive society. That we lock up so many of our own citizens indicates a tendency to punish people more severely relative to the practices of other nations. While incarceration rates are a popular indicator of a punitive criminal justice system, they capture only one aspect of crime policy and overlook such important features as the use of the death penalty, treatment of juveniles, and prison conditions. All of these practices are important and each contributes to a crime policy environment characterized by a tough law-and-order approach that favors law-enforcement spending over social investment and has resulted in large racial disparities in the jails and prisons.

To understand the factors that affect criminal justice policy choices, my colleagues and I looked at variation across several types of punishment practices in the states: political and symbolic punishments (including the application and use of the death penalty, felon disenfranchisement laws, and “three strikes” laws); incarceration practices (including average length of time served for manslaughter, rape, armed robbery, burglary, and auto theft); arrests for immorality crimes (such as prostitution, gambling, drug abuse, and drunkenness); conditions of confinement (including prison overcrowding, medical care costs per inmate, incidence of inmate deaths, prevalence of inmate-on-inmate and staff-on-inmate sexual violence); and juvenile justice practices (including juvenile transfer laws, incidence of juvenile inmates in adult prison, age of juvenile court jurisdiction). The data for this study covers criminal justice policy from 2002 to 2007 and was compiled by Besiki Kutateladze.

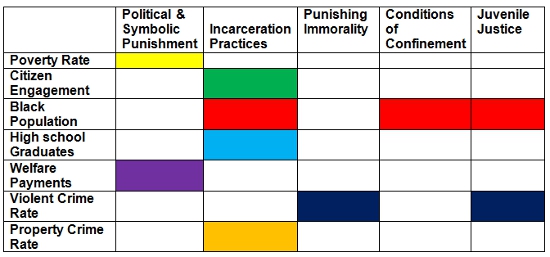

We looked at a variety of factors that could influence these different policy areas, including the size of the Black population, the percent of residents who graduated from high school, the percent of eligible voters who vote, the poverty rate, welfare generosity, median income, and the violent and property crime rates. We found that these factors, which play a role in influencing policy, vary by each policy area, as Table 1 illustrates. Criminal justice policy, therefore, cannot be classified as uniform or monolithic.

Table 1 – Factors affecting state punishment policies

Note: Each colored square shows a statistically significant factor affecting a state’s punishment policy.

For example, states with more stringent welfare programs are likely to have harsher punishments that reflect the public discourse on such crime policies as the death penalty and “three strikes” laws. This likely reflects a tradeoff some states make between addressing marginalized populations through the criminal justice system or the welfare system. States that spend more on welfare may choose to direct fewer resources towards criminal justice. They also may feel less need to emphasize harsh crime policy because marginalized populations are seen as less threatening or more deserving of assistance than they are in less generous states. Welfare policy, however, is not tied to the other crime policy areas studied here.

Black population size is significant in three policy areas: incarceration practices, conditions of confinement, and juvenile justice policies. States with larger Black populations are likely to be more punitive in each of these areas, after controlling for crime rates. This suggests that where Blacks are a larger segment of the population, there is a greater desire to control and contain them. These findings echo other research that has found that white citizens are more supportive of tough crime policy when they think it is directed towards Blacks.

As for the effect of crime on crime policy, higher rates of property crime are associated with less punitive incarceration practices. Property crime does not impact any of the other crime policies studied here. This suggests that criminal justice policy decisions are not very dependent on property crime, which includes burglary, larceny, motor-vehicle theft, and arson.

Violent crime, however, may be more significant. States with more violent crime, which includes murder, assault, rape, and robbery, are likely to arrest more people for “immorality” crimes such as prostitution and drug abuse. While it may be puzzling that incidents of violent crime effects the enforcement of laws against nonviolent offenses, this may reflect a law-enforcement practice of pursuing the low-hanging fruit of visible crimes in order to combat more serious crime. Higher rates of violent crime are also associated with harsher policies for juvenile offenders. This may indicate that criminal justice policy is a reaction to crime or it may reflect a tendency among citizens and the media to overestimate the extent of violent juvenile crime.

Overall, these findings are a strong indication of the uniqueness of different criminal justice policy areas. It is important to keep this in mind when discussing why the criminal justice system is the way it is. To lump all crime policy together obscures important nuances in types of policy that may be relevant to moving forward with criminal justice reform.

That said, one of the more consistent findings from this study is that Black population size is tied to greater punitiveness in several areas of criminal justice policy. This may not be surprising given that Blacks, especially young males, are arrested and incarcerated at much higher rates than whites. The effect of race on criminal justice policy, however, is troubling, particularly in light of a recent studythat found that whites are less likely to support criminal justice reform if they think Blacks are the ones being imprisoned by current laws. Such a finding indicates that appealing to concerns over racial disparities is not a way to win white citizens’ support for reform.

This study sheds light on some of the factors that affect criminal justice policy decisions, but it also raises more questions about how choices are made. Continued exploration of this policy arena is important. Tough-on-crime policies that have resulted in mass incarceration come with significant costs in taxpayer dollars, worker productivity potential, and civic engagement and trust among the minority populations that are disproportionately sent to prison.

If appealing to society’s moral compass cannot affect change, appealing to its pocketbook might. We have seen this strategy used in the debate over drug policy reform, particularly marijuana reform. Harsh sentencing practices result in more people’s being incarcerated for longer periods of time, an expensive and unsustainable outcome. Thus, a good way to begin a dialogue about punishment reform may be to focus on fiscal motivations.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Explaining Dimensions of State-Level Punitiveness in the United States: The Roles of Social, Economic, and Cultural Factors’, in Criminal Justice Policy Review.

Featured image credit: Connor Tarter (Flickr, CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1m8ijld

_________________________________

Katharine A. Neill – Rice UniversityKatharine A. Neill is the Alfred C. Glassell III postdoctoral fellow in drug policy at the Baker Institute of Public Policy at Rice University. Her current research focuses on state sentencing policies for drug offenders and the legalization of medical and recreational marijuana. Neill’s other research interests include criminal justice policy, the private prison industry and the use of public-private partnerships to deliver public services. She has published in several peer-reviewed journals in various policy areas, including crime, energy and environmental policy.

Katharine A. Neill – Rice UniversityKatharine A. Neill is the Alfred C. Glassell III postdoctoral fellow in drug policy at the Baker Institute of Public Policy at Rice University. Her current research focuses on state sentencing policies for drug offenders and the legalization of medical and recreational marijuana. Neill’s other research interests include criminal justice policy, the private prison industry and the use of public-private partnerships to deliver public services. She has published in several peer-reviewed journals in various policy areas, including crime, energy and environmental policy.

This is a just and well balanced opinion on government criminal policy. It is a pity to realize that the majority of lawmakers do not pay much attention to the morality of the law