Greenland will hold elections on 28 November following an expenses scandal involving Prime Minister Aleqa Hammond, which led to the collapse of the government. Ulrik Pram Gad writes that while there is strong support within Greenland for establishing independence from Denmark, the recent political turmoil has undermined plans to use investment in extractive industries such as mining as the basis for an independent economy. He argues that the situation could present an opportunity for the EU to engage in closer bilateral co-operation with the country, particularly given Greenland’s natural resources and renewable energy potential.

Greenland will hold elections on 28 November following an expenses scandal involving Prime Minister Aleqa Hammond, which led to the collapse of the government. Ulrik Pram Gad writes that while there is strong support within Greenland for establishing independence from Denmark, the recent political turmoil has undermined plans to use investment in extractive industries such as mining as the basis for an independent economy. He argues that the situation could present an opportunity for the EU to engage in closer bilateral co-operation with the country, particularly given Greenland’s natural resources and renewable energy potential.

On 29-30 September, Greenland saw the most dramatic 24 hours in the political life of its young democracy. A few days before the opening of the autumn session of its parliament, the Inatsisartut, the parliamentary auditing committee issued a press release saying that prime minister Aleqa Hammond, leader of the social-democratic Siumut party, had built up a debt of 106,363 Danish krone (approximately 14,000 euros) by letting the public purse pay for her family’s air fares, her hotel minibars, and private use of government reception rooms. The public reaction was made clear during the traditional procession from the tiny cathedral in Greenland’s capital, Nuuk, to the opening of parliament – arguably the most aggressive demonstration in the history of Greenland. After completing her opening speech, Ms. Hammond survived a vote of no confidence, only to seek and be allowed a leave of absence from her position.

Having survived the first day, however, the government coalition spectacularly imploded the following morning when three government ministers announced that they had to withdraw from their positions. During the press conference, a fourth minister joined them – and the newly elected chairman of the minor coalition partner Atassut (translated as ‘link’ – i.e. the ‘link’ to Denmark) entered the room and added that his party no longer supported the government. A long day of frenzied activity in the hallways of parliament followed, with members of Siumut trying to persuade the leading opposition party, the left-wing separatist Inuit Ataqatigiit, to enter a new coalition – anything to avoid an election. In the evening, the speaker of the parliament, a Siumut veteran, was convinced by a petition signed by a majority of members of parliament to call a special session in which Kim Kielsen, Minister for the Environment and acting as a substitute for Ms. Hammond, called a general election for 28 November.

Thus ended the 18 months of Aleqa Hammond’s rule: a suitably tumultuous ending given the experience of her government. One minor coalition partner, the Inuit Party, had left after a few months, and a former prime minister and chairman of the Siumut party, Hans Enoksen, left to form a new party, Partii Naleraq. Only two of the permanent deputy ministers – in principle politically neutral civil servants – are still in their positions. Having campaigned vehemently against the allegedly undemocratic ways in which the former government had conducted its policies on extractive industries, Ms. Hammond’s new majority scrapped a ban on mining uranium without much in the way of public consultation and through a condensed parliamentary procedure.

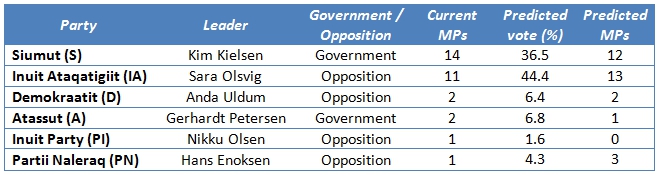

Table: Political parties and polling ahead of the 2014 election in Greenland

Note: Polling numbers are from the latest polling in September. Greenland’s elections use proportional representation in multi-member constituencies.For more information on the parties see: Siumut (S); Inuit Ataqatigiit (IA); Demokraatit (D); Atassut (A); Inuit Party (Partii Inuit – PI); Partii Naleraq (PN).

Only a small number of (largely unreliable) opinion polls have surveyed the 40,000 strong electorate in Greenland, with the results of the latest poll shown in the Table above. But based on electoral history, Kim Kielsen and Siumut’s chances are not as bleak as one might imagine. Since the introduction of party politics in 1979, Siumut has always succeeded in winning a majority or building coalitions. While minor parties have come and gone, and quick fix solutions to Greenland’s socio-economic problems have periodically attracted attention and votes, individual candidates have often emerged in one election only to fall flat in the next.

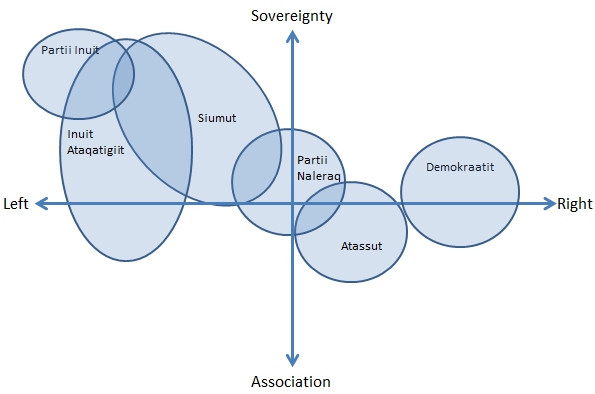

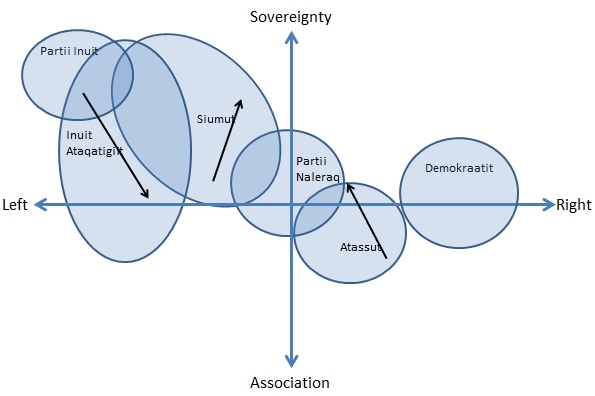

However following the 2009 introduction of an enhanced version of self-government within the Danish ‘Community of the Realm’, an unlikely coalition of the former-Marxist Inuit Ataqatigiit and neo-liberal Demokraatit (Democrats) ousted Siumut from power for the first time and proved surprisingly stable. Nevertheless, after four years of promising ‘nothing but sweat and tears’ to prepare Greenland for independence, Ms. Hammond swept the 2013 polls with a more generous approach offering independence ‘within her lifetime’ and both welfare and subsidies for settlements and small businesses intact. The Figure below shows where each of the parties are located on an ideological scale based on their stance on left/right issues and the issue of Greenland’s relationship with Denmark.

Figure: Greenland’s party system

[fusion_tabs layout=”horizontal” backgroundcolor=”” inactivecolor=””]

[fusion_tab title=”Party position”]

[/fusion_tab]

[fusion_tab title=”Inter-party variation”]

[/fusion_tab]

[fusion_tab title=”Recent shifts in party position”]

[/fusion_tab]

[/fusion_tabs]

Note: The figure shows three charts. In the first chart, each party’s position is shown based on where their current platform falls on a left/right scale and a scale indicating their stance on closer association/sovereignty from Denmark. The second chart shows inter-party variation (indicated by circles for each party) while the third chart shows the direction in which parties have moved in recent history. Figures are from the author’s upcoming book, ‘National Identity Politics and Postcolonial Sovereignty Games: Greenland, Denmark, and the European Union’ (Museum Tusculanum Press, 2015).

This time around, most parties have new leaders. One of them, Inuit Ataqatigiit’s Sara Olsvig, is most likely to be the country’s next prime minister. She holds a Master’s degree and in terms of public appearance offers a stark contrast to her most likely contenders: Mr. Kielsen, who proudly presents his stock of whale, seal and reindeer meat (single-handedly killed) to visiting journalists, and Mr. Enoksen, a former shopkeeper from a small village who consistently sticks to Greenlandic (never Danish) when speaking in public.

Future challenges: mining and Greenland’s relationship with Europe

While potential investors in Greenland’s nascent extractive industries might have preferred the policies and stability of the 2009-2013 coalition, Inuit Ataqatigiit’s likely return to power may involve yet another reversal of crucial elements in the country’s regulation of the industry. In a global market which is currently reluctant to take on new high risk projects – whether these are political risks or pertain to the (literally) uncharted Arctic waters – the immediate perspectives for developing the sector to be the engine of a self-sufficient Greenlandic economy are less than ideal. The most mature project, an iron mine near the capital Nuuk, recently suffered a serious blow as the license holder, London Mining, folded due to ebola closing down its operations in West Africa. Meanwhile much heralded Chinese investments have yet to materialise.

Whoever forms the next government, an urgent rethink will be required when it comes to finding new development partners. Indeed, the new leadership might find that old partners are worth returning to. In 1985, Greenland was the first territory ever to leave the European Community, following which it took on the status of an associated ‘overseas country and territory’. In the next two decades, a fisheries agreement formed the central instrument for co-operation between Greenland and the EU.

Since 2006, however, a general partnership has supplemented fisheries. The partnership agreement, renewed earlier this year, provides for co-operation on both minerals and energy. Outside of some still to be located oil deposits and yet to be developed mineral deposits (of which there is an abundance, from zinc, via rare earth elements to uranium), Greenland also has immense untapped hydroelectric potential. From the EU’s perspective, a more enhanced partnership with Greenland may therefore be worth exploring, given Europe’s twin goals of transitioning to green energy while freeing itself from dependence on Russian gas.

Featured image: Qaqortoq, Greenland, Credit: Greenland Travel (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

This article originally appeared at the LSE’s EUROPP – European Politics and Policy blog.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1G2xa7h

_________________________________

Ulrik Pram Gad – University of Copenhagen

Ulrik Pram Gad – University of Copenhagen

Ulrik Pram Gad is a post-doctoral fellow at the Center for Advanced Security Theory at the University of Copenhagen. He recently finished a collaborative project comparing the ‘sovereignty games’ involved in the EU relations of a series of ‘overseas countries and territories’ plus the Nordic micro-polities. His current research focuses on Greenlandic postcolonial politics and on the securitisation of Muslims in Denmark.