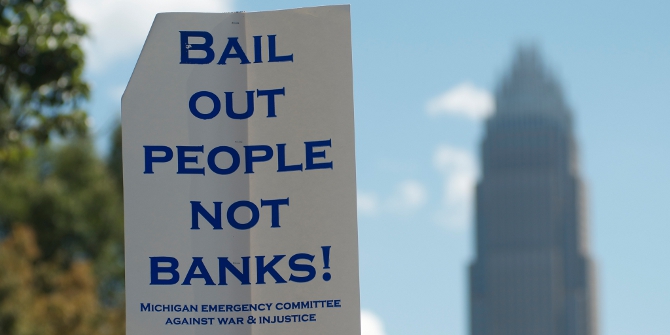

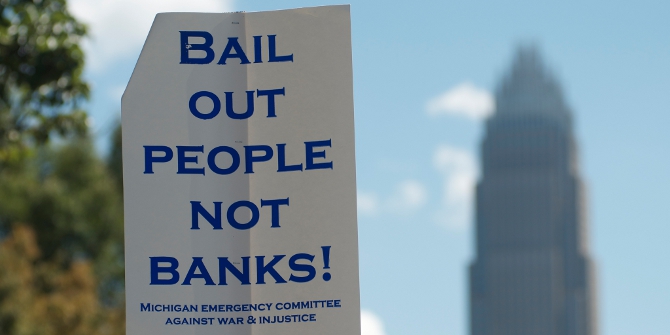

In 2008 politicians in the UK and the U.S. put in place massive bailout programs worth billions of dollars to save their ailing financial institutions. Six years on, U.S. taxpayers have made nearly $10 billion on their bailout investment, while those in the UK have lost around $14 billion. Pepper D. Culpepper writes that this difference is down to a combination of regulatory power and policy design. Regulators in the U.S. were able to require even those banks that were financially fit to accept money in exchange for stock because those banks earned the majority of their revenue locally. UK regulators on the other hand, were constrained by the vast market power of HSBC, which has only 20 percent of its business in the country, meaning that the bank was able to reject proposals that it take public money.

In 2008 politicians in the UK and the U.S. put in place massive bailout programs worth billions of dollars to save their ailing financial institutions. Six years on, U.S. taxpayers have made nearly $10 billion on their bailout investment, while those in the UK have lost around $14 billion. Pepper D. Culpepper writes that this difference is down to a combination of regulatory power and policy design. Regulators in the U.S. were able to require even those banks that were financially fit to accept money in exchange for stock because those banks earned the majority of their revenue locally. UK regulators on the other hand, were constrained by the vast market power of HSBC, which has only 20 percent of its business in the country, meaning that the bank was able to reject proposals that it take public money.

Six years after both the infamous American bank bailout and its better-received counterpart in Britain, policymakers continue to wrestle with the problem of how to deal with banks that are too big to fail. The latest policy proposal comes from the International Financial Stability Board, a body of heavyweight regulators and central bankers tasked by the G-20 countries with devising a set of guidelines for governments to impose on those banks deemed to be of global systemic importance.

At issue is how to solve the problem of moral hazard that lay at the heart of the 2008 bailouts. Governments were forced to save systemically important banks to keep the international financial system from freezing up, thus demonstrating that large banks can take advantage of their centrality to global finance to place risky bets, knowing they will be bailed out if their bets go wrong. The most recent proposal is to increase the amount of capital such financial behemoths are required to hold, so as to shift the costs of any future crisis to the banks and their shareholders, and thus away from taxpayers, who footed the bill in 2008.

The problem of moral hazard is central to the discussion of how to avoid future bailouts, and appropriately so. Regulators should hold banks that are too big to fail to a different standard, because of the costs their bad decisions can lay at the feet of taxpayers. Bailouts are a product of past failures to regulate this system appropriately.

Yet we live in an imperfect world; and bailout policies themselves should not be judged by the extent to which they punish the CEOs of banks who have made bad bets. Instead, given the existence of the moral hazard problem, bailout policies should be assessed by how well they protect taxpayers – since taxpayers are the ones who wind up paying for bailouts in the end.

Seen in this light, the bailouts in the UK and the US tell a different story. The conventional wisdom sees the American bailout as a gift from the Republican administration to the nine largest US banks: the banks received $125 billion and none of their CEOs was fired. In Britain, by contrast, the Labour government poured $111 billion into two its largest banks, but that help was costly: the CEOs of the banks were fired, and other large banks were asked to raise private capital to reinforce their balance sheets. From a moral hazard perspective, the UK bank bailout looks like much the better policy, which is how it has been treated in press accounts ever since.

The problem is this: the UK has a book loss of about $14 billion of its investment in the banks RBS and HBOS, while the US made about $8-10 billion on its bank investment. In other words, though the bailout is wildly unpopular in US public opinion, American taxpayers made a tidy profit on their bailout, while British taxpayers have lost money. Why has the conventional wisdom, which sees the bailouts as the endpoint of the creeping capture of the US government by its largest financial institutions, so badly misunderstood these facts?

As Raphael Reinke and I show in recent research, the tale of two bailouts is a product of policy design and regulatory power. At the moment of the bailout, the American government was able to force its largest banks to sign on to a policy that allowed taxpayers to share in the potential gains to healthy large banks of a bailout package. By requiring even the financially fit banks, JP Morgan and Wells Fargo, to accept government money in exchange for warrants to buy stock at its depressed crisis-price, the US was able to share with its taxpayers the upside that the bailout offered large banks.

This different policy was not a matter of different governmental preferences in the two countries. The British government also recognized the virtues of a collective plan that would have forced all large banks to take government money. Yet the British government faced a powerful opponent, over which it held limited leverage: HSBC, a large player in the British market, but a bank based in Asia, which does just twenty percent of its business in the United Kingdom. HSBC was able to reject the proposal of the Labour government that it take public money, because it was in a position in which UK regulators could do only limited damage to its future prospects. This contrasted with the case of the healthy American banks: JP Morgan earned more than 70 percent of its revenue in the US, and Wells Fargo 100 percent. Banks so heavily dependent on the US market were unable to defy the threats of American regulators, given the costs those regulators could impose on them in the future.

The story of these bailouts is indeed one of the power of banks. Yet the power that matters is a function of the economic footprint of banks, not their lobbying strength. The different fate of the two bailouts should lead scholars and policymakers to pay increased attention in the future not merely to the lobbying muscle of banks – what political scientists call their “instrumental power” – but equally to the way in which their role in national economies gives them “structural power” in dealings with government. HSBC was powerful not because of its overweening role in the British economy, but because Britain was a relatively small part of its overall business profile. In other words, the relationship of structural power is one of mutual dependence. HSBC was structurally strong in its dealings with the UK government because it was relatively less dependent on the British market than were its counterparts in the US market. No healthy large bank in the American market had the credibility to defy American regulators, given their future dependence on the American market. As a result of this structural power of the US government, American taxpayers were able to share some of the upside of the bank bailout – even if most American voters don’t know it.

This article is based on the paper ‘Structural Power and Bank Bailouts in the United Kingdom and the United States’, in Politics & Society.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/11fVt12

_________________________________

Pepper D. Culpepper – European University Institute

Pepper D. Culpepper – European University Institute

Pepper D. Culpepper is Professor of Political Science at the European University Institute in Italy. His research focuses on the intersection between capitalism and democracy, both in politics and in public policy. He is the author Quiet Politics and Business Power (Cambridge University Press 2011), winner of the 2012 Stein Rokkan Prize for Comparative Social Science Research, and of Creating Cooperation (Cornell University Press, 2003).

“American taxpayers made a tidy profit on their bailout”

This is technically correct but I can’t understand how this article can ask

“Why has the conventional wisdom, which sees the bailouts as the endpoint of the creeping capture of the US government by its largest financial institutions, so badly misunderstood these facts?”

Through systemic fraud and profound incompetence the US financial institution inflicted a truly devastating blow to the US economy. They failed. They were bankrupt and then the US government offered them preferential treatment and bailed them out.

I think that’s the textbook definition of corporate creeping capture.

What worries me most is how disingenuous the argument in this article is. The author only concentrates on direct government aid and does not mention the response of the central banks.

The author can say that the US governments response was more efficient and I think he makes a compelling argument that market power was a determining factor in shaping the US and UK bailouts. However the author can’t make the argument that US citizens have “badly misunderstood” the bailout. I think when people see cronyism on an epic scale they understand the “creeping capture of the US government” better than the author.