The terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001 drew worldwide attention to the phenomenon of anti-American transnational terrorism. Given the frequency of and dangers associated with anti-American terrorism, the U.S. government tries to protect itself by giving foreign assistance to countries from which anti-American aggression originates. Studying the nexus between U.S. economic and military aid, local human rights conditions and the emergence of anti-American transnational terrorism in aid-receiving countries, Thomas Gries, Daniel Meierrieks and Margarete Redlin, however, find no evidence that the U.S. is made any safer by providing assistance. Rather, they find that economic and military aid—even if given to local regimes that are highly repressive in their fight against terrorism—results in more anti-American terrorism originating from aid-receiving countries.

The terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001 drew worldwide attention to the phenomenon of anti-American transnational terrorism. Given the frequency of and dangers associated with anti-American terrorism, the U.S. government tries to protect itself by giving foreign assistance to countries from which anti-American aggression originates. Studying the nexus between U.S. economic and military aid, local human rights conditions and the emergence of anti-American transnational terrorism in aid-receiving countries, Thomas Gries, Daniel Meierrieks and Margarete Redlin, however, find no evidence that the U.S. is made any safer by providing assistance. Rather, they find that economic and military aid—even if given to local regimes that are highly repressive in their fight against terrorism—results in more anti-American terrorism originating from aid-receiving countries.

In recent years the U.S. government has increasingly tied its foreign assistance policy to national security concerns. Here, one goal of U.S. aid is to reduce U.S. vulnerability to transnational terrorism by delegating the fight against a common enemy (i.e., terrorist organizations) to the source countries of terrorism. However, there is little empirical support that this idea actually works. Rather, the evidence suggests that activist foreign policies are associated with more (anti-American) terrorism. Hence, an important question is:

Why is the U.S. more vulnerable to terrorism originating from countries receiving the most development and military aid?

The augmentative effect of U.S. aid on anti-American terrorism may be due to the idea that “the friend of my enemy is my enemy”. As argued by earlier studies, it may be attractive for terrorist groups to internationalize a domestic conflict by targeting foreign allies (i.e., the U.S.) that stabilize the government they oppose. Even though these terrorist groups ultimately have domestic ambitions, attacking the United States as a foreign sponsor may stir up domestic support for their cause and improve terrorist mobilization.

The role of local repression

Besides this strategic logic, the eventual effect of U.S. support on anti-American terrorism may, however, also be contingent upon local (economic, political, and cultural) conditions in the aid-receiving country. Still, the conditioning effect of local conditions on the emergence of anti-American terrorism has so far received little attention in academic research. Our empirical analysis aims at filling this research gap. Here, we focus on the (conditioning) role of local repression.

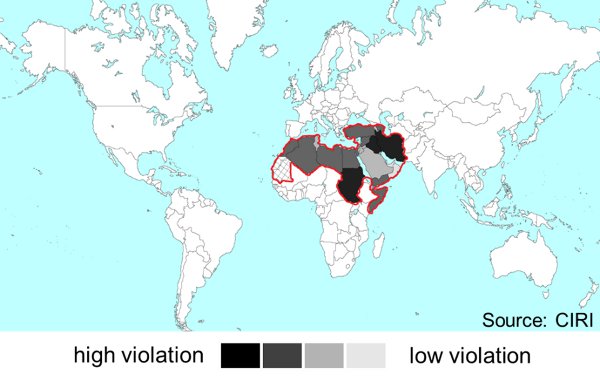

In recent years the argument has been brought forward that anti-American resentment (which may also result in anti-American terrorism) is a consequence of U.S. support for repressive local regimes. Critical voices (e.g., Noam Chomsky) argue that U.S. aid all too often—and deliberately—falls into the hands of oppressive governments. Local repression coupled with U.S. aid may indeed explain why this aid is deemed unwelcome and thus results in additional anti-American grievances. Trends and patterns in terrorism since the end of the Cold War provide tentative support for this idea. Many terrorist attacks against U.S. interests (most notoriously, the 9/11 attacks) have been conducted by perpetrators from the Middle East and Northern Africa (MENA). At the same time, many countries in this part of the world receive substantial U.S. aid and also feature repressive regimes, e.g., in Egypt and Iraq (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Physical integrity rights violations in the broader MENA region

Here, the argument is that aid is purposely given by the U.S. to buy political support from recipient countries. For instance, it may be in the interest of the United States to deliberately use aid to foster economic change (e.g., an opening of local markets to U.S. products and capital) that benefits the United States. This may already cause anti-American resentment. However, the combination of U.S. aid and local repression creates additional grievances that are specifically directed against the United States. Here, due to its support for repressive local regimes, the United States becomes associated with— and tainted by—local repression, the argument (e.g., voiced by Osama bin Laden in his “Letter to America”) being that the United States deliberately uses aid to freeze local political developments (i.e., democratization), instead supporting local repression. In other words, it is argued that aid is purposely given by the U.S. and used by the (dependent) local government to uphold local repression, which serves both the interests of the U.S. and the local government. In consequence, support from the U.S. government for an unpopular—oppressive—local regime may correlate with rising discontent projected onto the United States, which may ultimately result in anti-American terrorism.

The nexus between U.S economic and military aid, human rights, and terrorism

To analyze the potentially interacting effects of dependence and repression we study the nexus between U.S. economic and military aid, human rights and anti-American terrorism using panel data from 126 countries for the period between 1984 and 2008. We show that the combination of local oppression and economic and particularly military aid indeed leads to more anti-American terrorism. The estimated effects are also (economically) substantive. For instance, a country with a substantial level of human rights violations (indicated by the use of torture, extrajudicial killings, disappearances and political imprisonments) that receives the mean amount of military aid from the U.S. (approx. 0.043% of local GDP) generates about 10 times more anti-American terrorism compared to a baseline country that receives the same level of aid but does not exert repression. Our findings support those voices that are critical of U.S. interventionism.

The positive association between military-economic dependence on the United States and anti-American terrorism generated in the aid-receiving country only weakens (i.e., is no longer statistically significant) when U.S. aid becomes very large; this may be due to increased capacity of oppressive regimes—possibly further incentivized by the prospect of future American support—to adopt harsh counterterrorism measures. However, we find no evidence at all (even after accounting for endogeneity) that the U.S. is made any safer by providing assistance to the source countries of terrorism, even if this assistance is very large and/or channeled to particularly oppressive regimes. Our analysis thus provides little support for the official U.S. government notion that foreign aid may be part of an effective U.S. strategy to prevent anti-American terrorism. To the extent that U.S. foreign assistance creates benefits not related to security (e.g., access to foreign markets), the United States may therefore face a trade-off between securing these benefits and being vulnerable to terrorism.

This article is based on the paper “Oppressive governments, dependence on the USA, and anti-American terrorism”, forthcoming in the Oxford Economic Papers.

Featured image: Humanitarian aid shipment to Iraq, 2003 Credit: Think Defence (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1suOePY

_________________________________

Thomas Gries – University of Paderborn, Germany

Thomas Gries – University of Paderborn, Germany

Dr. Thomas Gries is a Professor of Economics at the University of Paderborn. His teaching and research focU.S.es on Economics of Conflict, Economic Policy, European Union Economics, Political Economy, Institutional Economics, Financial Economics and Development Economics.

_

Daniel Meierrieks – University of Freiburg, Germany

Daniel Meierrieks – University of Freiburg, Germany

Dr. Daniel Meierrieks is a Research Fellow at the Department of Economics at the University of Freiburg. His research focuses on Economics of Terrorism and Security, Development Economics, Financial Economics, Political Economy and Public Economics.

_

Margarete Redlin – University of Paderborn, Germany

Margarete Redlin – University of Paderborn, Germany

Dr. Margarete Redlin is a Research Associate at the Department of Economics of the University of Paderborn. Her primary research interests include Economics of Conflict and Development Economics.

1 Comments