America’s prisons are becoming increasingly overcrowded, with many authorities seeking to shift the supervision of offenders into the community as a result. In new research, Jordan M. Hyatt & Geoffrey C. Barnes investigate the use of intensive supervision for the most serious offenders. In a study of more than 800 high risk probationers, they find that those who were closely supervised were just as likely to reoffend as those who were not, and in a similar time frame. They also find that closer supervision is linked with higher rates of absconding, incarceration and probation violations.

America’s prisons are becoming increasingly overcrowded, with many authorities seeking to shift the supervision of offenders into the community as a result. In new research, Jordan M. Hyatt & Geoffrey C. Barnes investigate the use of intensive supervision for the most serious offenders. In a study of more than 800 high risk probationers, they find that those who were closely supervised were just as likely to reoffend as those who were not, and in a similar time frame. They also find that closer supervision is linked with higher rates of absconding, incarceration and probation violations.

Prison overcrowding is an increasingly vexing problem in the United States. One solution has been to shift the supervision of more offenders, through a variety of mechanisms, away from prisons and into the community. This has contributed to the creation of a large probation and parole population. When more serious offenders are supervised within the community, the natural and most common policy response has been to increase the intensity of their supervision.

Intensive supervisory probation (ISP) can take many forms. The goal is simply control: to provide as much oversight of the probationers as is possible within the community. Protocols of this nature often require frequent meetings with a probation officer, regular drug testing, police or probation officers visits to homes and contacts with family members and employers. Prior studies of ISP have not been supportive of the practice, but the policy persists in many jurisdictions.

High-risk offenders may pose a danger to the community and it is important that the effects of community supervision policies on recidivism be understood. Our research shows that, despite exhausting limited resources, this strategy has little appreciable impact on crime and results in increases in undesirable behaviors, including failures to comply with the rules of probation, increases in court hearings and, eventually, jail time.

In Philadelphia, researchers from the Jerry Lee Center of Criminology (JLC) at the University of Pennsylvania, collaborating with Philadelphia’s Adult Probation and Parole Department (APPD), have worked to understand the impact of supervision intensity on recidivism. Since 2009, APPD has used a statistical risk forecasting model to assess all of their probationers. Predictions are made using a type of machine learning procedure known as “random forests.” This has allowed for the power of the large amount of data collected by the court system and probation department to be employed in making accurate risk forecasts. Probationers are supervised in keeping with this assessment: high-risk offenders receive more supervision and low-risk offenders receive less.

An earlier study by the collaboration found that, for non-serious offenders, decreasing the frequency of reporting to only twice a year and increasing the number of offenders assigned to each officer to almost 400 did not have an appreciable impact on crime. However, this policy preserved significant resources and allows the agency to focus on the individuals most likely to commit a serious crime and to harm others in the community.

Beginning in 2010, the collaboration conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) designed to isolate the impact of ISP on high-risk offenders. Common in medicine, randomized trials allow for the identification of cause-and-effect relationships and are one of the strongest forms of evidence available in the social sciences.

For this study, 832 high-risk, male probationers were randomly assigned into two groups: 447 individuals received ISP and 385 individuals were supervised under a much less restrictive protocol. With the exception of the type of supervision they were to receive, the groups were statistically identical. All offenders were supervised in their assigned manner for at least 12 months. During that period, data were gathered on their arrests, compliance with the rules of community supervision, drug use and if they were reincarcerated in the local jail system.

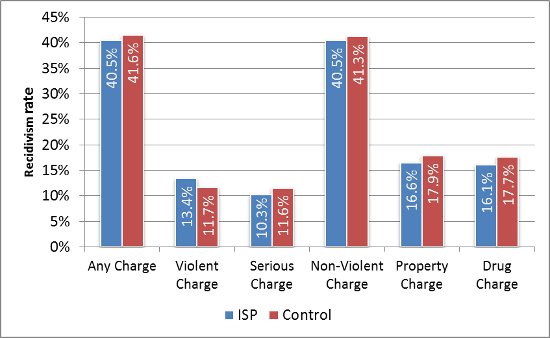

When comparing the recidivism rates of the two groups (Figure 1), it becomes clear that roughly equal percentages of both the ISP group (40.5 percent) and the comparison group (41.6 percent) were charged with a new offense within a year. This remains the case even when these offenses are broken down by type, including violent, serious, non-violent, property, and drug offenses. The same trend is evident is when counting the number of new arrests of each type; ISP had little impact on new crimes.

Figure 1 – Recidivism rates for Intensive supervisory probation and Control groups

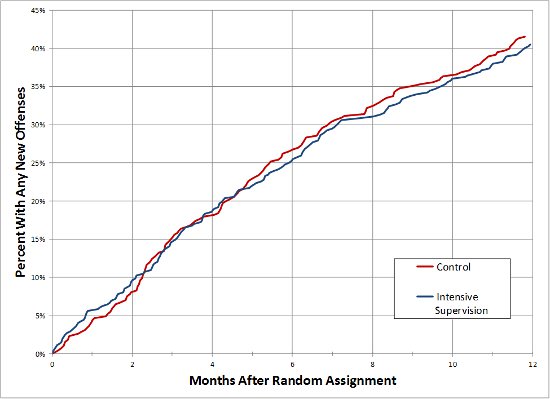

Since ISP is a control and surveillance focused approach to supervision, it was thought that perhaps criminal activity would have been detected earlier. However, there were no significant differences in how long probationers remained on supervision before offending. Figure 2 shows the “time to failure,” that is how many days elapsed before an individual in the experiment was arrested for the first time. The fact that the two lines are almost identical illustrates that there was no meaningful difference between the groups. Similar analyses, conducted for each specific type of crime, also showed no difference.

Figure 2 – Days elapsed before individual in Intensive supervisory probation and Control groups’ first arrest

ISP did have an effect on other types of offender conduct, which is clear when examining additional measures of behavior. Within one year, for example, 11.2 percent more of the ISP group had absconded, that is failed to report to their officer for long enough that a warrant was issued for their arrest, than in the comparison group. 12.3 percent more of the ISP group was in custody, at least once, in the Philadelphia County Prison System. ISP offenders were also more likely to return to court for a violation hearing, in front of a judge, as a result of their failure to comply with the conditions of supervision. All of these differences are statistically significant. We can therefore conclude that elements of the ISP protocol were responsible for these undesirable outcomes.

Ultimately, the efforts dedicated to increasing the intensity of supervision may be better allocated elsewhere, including treatment, especially for agencies operating under significant resource constraints. Supervision focused on the integration of treatment and control-focused characteristics produces an opportunity to utilize community corrections as a mechanism to reduce offending. If nothing else, the increased contacts required under ISP create the opportunity to deliver evidence-based, violence-prevention programming. There are several options available in community corrections, though cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) remains one of the most promising approaches being explored by the research collaboration.

Especially in light of growth in community corrections, agencies and policymakers should consider the costs, in both expended resources and missed opportunities, of how supervision is used. ISP may alleviate political pressures to do something with high-risk populations, but, used alone, it is unlikely to reduce crime.

This article is based on the paper ‘An Experimental Evaluation of the Impact of Intensive Supervision on the Recidivism of High-Risk Probationers’, in Crime & Delinquency.

Featured image credit: Boyce Duprey (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of U.S.App– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1xU3y8S

_________________________________

Jordan M. Hyatt – University of Pennsylvania

Jordan M. Hyatt – University of Pennsylvania

Jordan Hyatt is currently the Senior Research Associate at the Jerry Lee Center of Criminology at the University of Pennsylvania, and also works with the Pennsylvania Commission on Sentencing and the Uniform Law Commission. His current research focuses on program evaluation in reentry and corrections, the impact of cognitive behavioral therapy on high-risk probationers and on integrating actuarial risk-assessments into sentencing decisions.

Geoffrey C. Barnes – University of Pennsylvania

Geoffrey C. Barnes – University of Pennsylvania

Geoffrey C. Barnes is a Research Assistant Professor of Criminology at the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Criminology. He works primarily on field experiments testing the effects of programs and policies on crime and justice outcomes. He has more than two decades of experience working with large and complex data systems, including those of different criminal justice agencies in Australia, England, and the United States.

Issues that impact any study of the effectiveness of intensive supervision:

How “intensive” is intensive supervision?

What is the amount of supervision for high-risk non-intensive cases?

Are POs able to immediately detain an offender found to be in violation?

Are there serious efforts to locate and arrest absconders?