Andrew F. Cooper provides an in-depth study of the motivations, methods, and contributions made by former leaders as they take on new responsibilities beyond service to their national states. This is a thought-provoking read for students of politics and personalities, finds Stephen Minas.

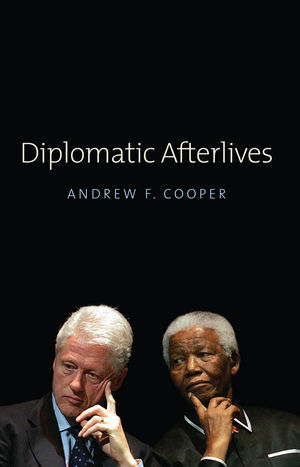

Diplomatic Afterlives. Andrew F Cooper. Polity. 2014.

Diplomatic Afterlives. Andrew F Cooper. Polity. 2014.

As diplomats gathered in New York to negotiate the successor to the Millennium Development Goals, and the World Economic Forum convened in Davos in early 2015, the fluid and fragmented state of global governance was on display.

Nations struggling to get to grips with cross-border challenges are confronted by what appears to be an ever more complex scene, which includes the intensification of collective action problems such as climate change; the diffusion of power and agency, from developed to developing countries and from the West to Asia and other regions; and the emergence of non-hierarchical and ‘hybrid’ forms of governance, with markets, standardizers and the private and voluntary sectors joining nations and intergovernmental organizations in shaping the global order. These observations have become common enough. But their consequences for our capacity to respond creatively to common threats are far from clear.

Diplomatic Afterlives, by Professor Andrew F. Cooper of the University of Waterloo’s Department of Political Science, is an interesting addition to the International Relations (IR) literature that examines some of these consequences. As a field, IR is no longer confined to theorizing about the unitary, ‘billiard ball’ states that fit into parsimonious models but so inadequately account for lived experience. The role of individuals, and individual agencies, inside the state system is now widely studied, e.g. in the subfield of Foreign Policy Analysis. But what about individuals outside the system?

The activities of influential private individuals and networks in global affairs have attracted greater scrutiny in recent years, e.g. in Superclass by Foreign Policy editor David Rothkopf. Cooper’s contribution focuses on one subset of this ‘power elite’: former world leaders who have built post-office careers as ‘freelance’ diplomats, including Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, Mikhail Gorbachev, Tony Blair and Nelson Mandela.

Diplomatic Afterlives begins with a consideration of how this group has broken with the traditional roles of ex-leaders, who became ‘wise counselors’ (Lee Kuan Yew), defended their ideological legacy (Margaret Thatcher) or made a ‘dash for cash’ (a phrase apparently coined to describe the ventures of former Australian Prime Minister Bob Hawke). The leaders Cooper studies forged ‘hybrid personae, situated in the nexus between traditional club membership and transnational diplomacy’. They became less embedded than other ex-leaders in the ‘state-centric system’ and were advocates of ‘transnational social purpose’, often relying on the ‘ability to deliver spectacle’ to advance their agendas.

Cooper moves on to consider each of his former leaders: Carter, who pioneered this ‘hybrid’ approach; Clinton, who institutionalized and expanded it; Gorbachev and Blair, whom Cooper sees as engaging in contested attempts to salvage their reputations; and Mandela, who leveraged his deservedly iconic status to pursue policy goals. Finally, Cooper briefly examines the impact of less prominent ex-leaders working collectively in networks. Cooper situates his book in what he terms IR’s shift in focus from the study of structure to agency and in the wider debate over ‘the trajectory of global governance’.

Parag Khanna once memorably claimed that ‘everyone who has a BlackBerry—or iPhone or Nexus One—can be their own ambassador’. Diplomatic Afterlives advances a very different – and altogether more sustainable – case: that the space for individual diplomacy open to a few ex-world leaders is so unique that even ‘second-tier former leaders’ have to band together to maximize their influence. Cooper argues that by utilizing non-state tactics (‘network power from below, lobbying, and self-organization’) while taking advantage of their privileged access within the state system, Carter, Clinton et al bridge the gap between ‘the worlds of public and private authority’. In doing so, they have expanded the ‘afterlife repertoire’ of ex-leaders beyond the mediatory work of ex-leaders’ clubs to more sustained work on major issues.For Cooper, these leaders are a particular form of ‘transnational norm entrepreneur’ and are emblematic of a ‘greater privileging of moral or normative claims’ in responses to transnational problems. Cooper concludes that, seen through ‘a sympathetic lens’, the new model of ex-leader activity is ‘an advance, an innovation in leadership’.

In the chapter on Bill Clinton – arguably the most prolific of the current ‘exes’ – Cooper examines the motivations, the possibilities and the risks of ex-leader diplomacy. Cooper sees Clinton as driven by a ‘sense of incompleteness or even guilt about his record’ on issues like HIV/AIDS. Clinton has ‘stretched’ the networking model pioneered by Carter to encompass business and celebrity partners as well as experts, enabling his initiatives to raise awareness of targeted issues and mobilize resources. While some have dismissed the Clinton Global Initiative’s annual New York summits as ‘the Oscars of global philanthropy’, Cooper finds that Clinton has demonstrated ‘steadfastness over a lengthy period of time’ on transnational social issues. Concurrently, high-profile missions like Clinton’s 2009 trip to North Korea to secure the release of two journalists serve to burnish his status as both a ‘club insider’ and a ‘transnational agent who could deliver results’. However, the ‘utmost primacy’ of fundraising in the Clinton project has exposed it to accusations of quid pro quos for donors. (Another threat to ex-leader projects is ‘trivialization’. Cooper cites a television commercial for Pizza Hut in which Gorbachev ‘took part in an argument among Russian pizza-eaters about the virtues of consumer capitalism’).

Diplomatic Afterlives begs the question of what wider lessons can be drawn from the activism of former world leaders regarding non-traditional diplomacy or the direction of global governance generally. Mandela was a surely one-off, and the exploits of each of the ‘hyper-empowered’ ex-leaders look like agency for the few, not the many. Cooper acknowledges that his book ‘reinforce[s] the impression of exceptionality’ of Mandela, Clinton et al. This is why the chapter on the evolving networks of ‘second-tier former leaders’ and other former officials is particularly important, as it anticipates an ongoing ‘team-oriented approach’ that does not rely on outliers.

In particular, Cooper hails the Elders initiative, founded by Mandela in 2007, as a ‘serious advance’, for several reasons: the initiative is an attempt to operationalize non-state ‘rapid response or just-in-time diplomacy’; it has ‘demonstrated that it can regenerate itself’; and the inclusion of figures like Kofi Annan and Desmond Tutu ‘demonstrated a shift from a closed to an open network’. Cooper acknowledges that the Elders lack a ‘defining moment’ in which they have been seen to make the difference in a crisis, but this is also true of the great bulk of state-to-state diplomacy. As Gareth Evans (not yet an Elder) once observed, ‘all diplomacy is in a sense preventive’.

The growing prominence of ex-leader networks is a sign of the times. When networks matter in global governance, former presidents, prime ministers and foreign ministers will be well placed to participate. Diplomatic Afterlives recognizes the deficiencies with the model, including lack of accountability and the potential for former leaders who might otherwise have left the stage to carry on acting regressively. Nevertheless, Cooper is correct to highlight the potential for ex-leaders to contribute to creative solutions to transnational problems. His book would make thought-provoking reading for students of IR and global governance.

This review originally appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1KtQrQi

——————————————–

Stephen Minas – King’s College London

Stephen Minas is a Research Fellow in the Transnational Law Institute, King’s College London and is working on a PhD on transnational law and climate change at King’s. Stephen is also a Research Associate with the Foreign Policy Centre and Honorary Fellow within the School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne. Stephen previously worked as an adviser to the Premier of Victoria, holds Honours degrees in Law and History from the University of Melbourne and an MSc in International Relations from LSE, and is admitted as an Australian lawyer. He tweets @StephenMinas. Read more reviews by Stephen.

1 Comments