One of the key provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, or ‘Obamacare’ was the expansion of Medicaid program across the states. The Supreme Court struck down the requirement for states to expand the program in 2012, and 20 states have since opted out. In new research, Charles Barrilleaux and Carlisle Rainey look at why state government have opted out of the Medicaid expansion. They find that political variables, such as Obama’s 2012 vote share and the governor’s partisanship are the best predictors of opposition to Medicaid expansion, rather than measures of need, such as life expectancy or the number of people that are uninsured.

One of the key provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, or ‘Obamacare’ was the expansion of Medicaid program across the states. The Supreme Court struck down the requirement for states to expand the program in 2012, and 20 states have since opted out. In new research, Charles Barrilleaux and Carlisle Rainey look at why state government have opted out of the Medicaid expansion. They find that political variables, such as Obama’s 2012 vote share and the governor’s partisanship are the best predictors of opposition to Medicaid expansion, rather than measures of need, such as life expectancy or the number of people that are uninsured.

Medicaid began in 1966 under President Johnson’s Great Society initiative, which expanded the national government’s role in health, education, and social welfare policies. Importantly, though, it relied upon state government’s accepting national financing–a carrot that induced states to provide services they would ordinarily not agree to provide. Even with a generous national government match (at least dollar-for-dollar, and some states get more generous matches), Medicaid has long been among the most expensive programs for states. Medicaid played a critical role in President Obama’s signature health care reform legislation, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), or “Obamacare.” The original version of the law required states to expand their Medicaid programs, covering a significant portion of the 50 million US citizens who were without health insurance. This requirement, though, came at little cost to the states. The national government would initially pay 100 percent of the cost of the expansion and this would only shrink to 90 percent over several years.

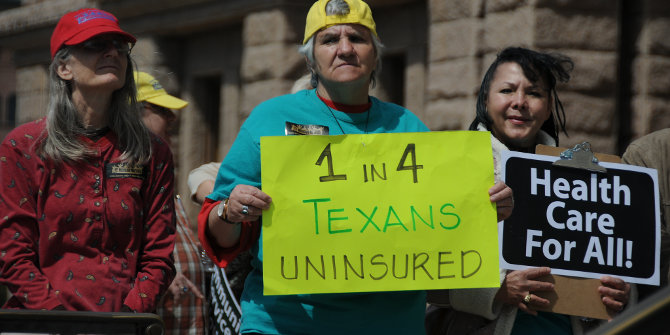

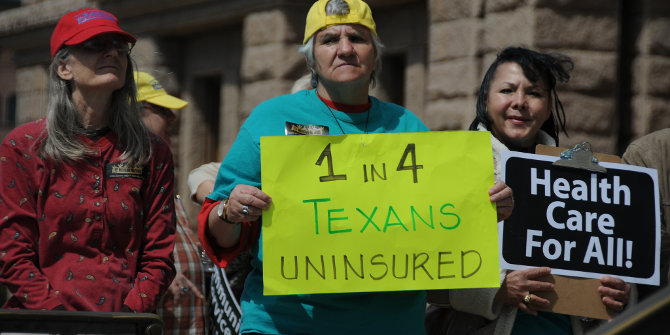

In 2012, however, the Supreme Court stuck down this requirement, noting that states must be granted the opportunity to opt-out. This gave states a choice: expand their Medicaid program and receive the generous benefits or refuse to expand their program and reject the benefits. These benefits are not trivial. For example, by simply accepting these benefits, Texas could have expected to prevent between 3000 and 1800 deaths.

Yet of March 2015, Texas, along with 20 other state governments, has decided not to expand their Medicaid programs, establishing a new politics of Medicaid policy in the United States. But why would states decline this money? In recent research, we ask why some governors opposed the PPACA Medicaid expansion in spite of the seemingly generous benefits. The law’s designers seemed to assume that even the most fiscally conservative states would expand their programs in order to greatly expand health insurance coverage in their states if the national government covered almost all of the cost. But we point out that many governors face a tension between political expedience and citizens’ needs. Politics and need pull many governors in opposite directions. We ask: In this tug-of war between politics and need, which one wins? Is it politics? Or is it need? To get at these questions, we conduct several statistical analyses and the answer seems clear: politics wins, hands down.

Partisan politics fuel Governors’ Medicaid decisions

As part of answering the question, we look at what variables best predict opposition. It turns out that variables capturing the political landscape best predict opposition: partisan control of the lower house, Obama’s vote share in 2012, the governor’s partisanship, and the average ideology of the states’ citizens. Measures of need, such as life expectancy, percent of the population uninsured, and heart disease death rates, are not helpful in predicting opposition.

But how big are these effects? We estimate that in otherwise “Republican” states (i.e., GOP-controlled legislature, 38 percent view ACA favorably), we find that a Republican governor is 49 percentage points more likely to oppose the expansion a Democratic governors. On the other hand, we estimate the percent uninsured in the state to have a small positive effect on the probability of opposition. This estimate suggests that governors of more needy states are more likely to oppose the expansion. While there is a large amount of uncertainty in this estimate, the data strongly suggest that partisanship has a larger effect than need.

In sum, our results reveal that partisan politics, not citizen need, explain governors’ decisions whether or not to accept the Obamacare Medicaid expansions as offered under the Affordable Care Act. While it comes as no surprise that Republican governors were more likely to oppose the expansion than Democratic governors, it is surprising that governors were much less responsive to citizen needs. Indeed, we find no evidence that need matters at all.

The Implications

Our results may also point to a new state level opposition to federal spending that seeks to induce state and local government policy choices. The original Medicaid policy was designed to lead the states to do what they would not ordinarily do. The program’s initial design promised to pay physicians and hospitals “customary and prevailing rates” and allowed states to establish generous eligibility standards. The national government has been trying to establish ways to provide high eligibility for Medicaid while controlling spending, but has not often succeeded. This move by a number of state governments not to expand the program even under the most generous of federal payment schemes shows stronger resolve to hold down costs and access to services among some conservative state governments.

The choice to expand Medicaid has important implications for citizens. The United States has reduced the number of its citizens who have no health insurance with the establishment and implementation of the ACA. The state governments that did not agree to expand Medicaid are receiving less federal money than they would spend to expand Medicaid.

The national government’s generous benefits to Medicaid programs are offered to state governments who cannot afford to provide Medicaid benefits, prefer not to provide the benefits, or otherwise would normally opt out of the program, but accept the federal payments because they expand coverage with low state cost. The costs of non-participation in Medicaid are enormous: the state of Florida, for example, turned away $50 million in subsidies in the 2014 fiscal year, leaving tens of thousands of person who might have had health insurance uninsured. In 2015, the national government halts payments to hospitals that provide a large amount of service to the uninsured, services that were once paid by national government transfers to not-for-profit and/or public hospitals, leading a number of those hospitals to suffer financial crisis. The rejection reveals states’ willingness to forgo national government financial contributions even if it results in less health coverage for the poor. The demands by eleemosynary (charitable) hospitals for continued support for the uninsured may lead some state governments that previously refused to expand Medicaid to find a way to accept federal government money by redefining the meaning of Medicaid expansion. For example, the national government may allow states to provide benefits that mirror Medicaid but are given a different name, thus allowing conservative state governments not to accept Medicaid expansion and the national government to expand coverage and retain support for the not-for-profit hospitals.

A 2014 report from the Urban Institute indicates that that cost to states of expanding Medicaid would be about $31.6 billion by 2016, but by doing so they would receive $423.6 billion in the form of Medicaid shares paid by the national government, as well as $167.8 billion from hospital payments that will cease after 2015. In addition, citizens of states that enroll in the Medicaid expansion will get better health care than citizens in non-Medicaid expanding states. Governors who do not expand Medicaid are doing so because of political belief, and the evidence suggests that those beliefs are not consistent with public preferences or public need.

On March 4, 2015 the U.S. Supreme Court heard another case that may further divide the U.S. along the lines of health care haves and have-nots. That case’s petitioners claim that only persons who reside in states that have established their own health exchanges may receive federal health care subsidies as are provided under the ACA. If the Court rules in favor of the petitioners, it will likely result in the collapse of the ACA in states that do not establish exchanges (which includes all of the non-Medicaid adopters as well as others that opted to use the federal exchange) and will create a truly divided system of health benefits in the United States. The system for the states that have adopted the ACA and whose citizens are eligible for subsidies will have a much stronger network of health care access, coverage, and providers that will states that either refused the Medicaid expansion or chose not to establish a health exchange. We will know in June 2015, when the Court decides, which of those systems we can expect to exist in the near future.

This article is based on the paper, The Politics of Need Examining Governors’ Decisions to Oppose the “Obamacare” Medicaid Expansion’, in State Politics & Policy. Gated version. Ungated version.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1Cj1dq9

_________________________________

Charles Barrilleaux – Florida State University

Charles Barrilleaux – Florida State University

Charles Barrilleaux is the LeRoy Collins Professor of Political Science at Florida State University. His primary areas of interest are in public policy and U.S. state and local government and politics. His research addresses questions of “who gets what” in politics, focusing on the effects of democratic rules and citizen preferences as explanations for the differences we observe among democracies.

Carlisle Rainey – The University at Buffalo

Carlisle Rainey – The University at Buffalo

Carlisle Rainey is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at UB. His work addresses the interaction between institutions and behavior and develops and refines statistical tools to address these substantive issues.