For decades, many have been concerned over pork barrel politics in Congress with power over the allocation of federal spending recently flowing towards the presidency as a counter. But what if presidents pursue policies that also channel federal grants to parts of the country that are electorally useful? In new research, Douglas Kriner and Andrew Reeves find that presidents allocate more federal resources (which are worth billions) to swing states, states which reliably back them in elections, and those which elect co-partisans that they are able to build coalitions with.

For decades, many have been concerned over pork barrel politics in Congress with power over the allocation of federal spending recently flowing towards the presidency as a counter. But what if presidents pursue policies that also channel federal grants to parts of the country that are electorally useful? In new research, Douglas Kriner and Andrew Reeves find that presidents allocate more federal resources (which are worth billions) to swing states, states which reliably back them in elections, and those which elect co-partisans that they are able to build coalitions with.

When it comes to pork barrel politics, Congress has repeatedly looked to the president to save it from itself. For instance, the Republican-controlled 104th Congress passed the Line Item Veto Act in 1996, giving President Clinton the authority to strike “wasteful” spending provisions in legislation. In 2010 following the midterm elections, the Republican House adopted a ban on earmarks, in effect giving more power to the executive departments and agencies over how federal spending is allocated. Despite a chorus of support for delegating these decisions to the executive branch, a few have voiced concerns over the increased influence of the executive branch in the distribution of federal dollars. Former Member of Congress Lee Hamilton (D-IN) complained in 2010 that, in passing earmark reform, Congress had “yet again opt[ed] to diminish itself while strengthening the President.”

While delegation to the president can break the gridlock in Washington, we argue that it does not produce an equitable allocation of federal resources across the country. Rather, electoral and partisan forces drive presidents to prioritize the needs and desires of some Americans over others. As a result, increased presidential power will continue to produce significant inequalities in the distribution of federal reflecting the president’s political interests.

Members of Congress wear two hats simultaneously. On one hand, they are members of the national legislature charged with crafting policies that serve the needs of the nation. Yet, they are also representatives of their narrow geographic constituencies, accountable for meeting the needs of their local constituents. The result is that congressional politics, particularly budgetary politics, are often parochial, with powerful members using their leverage to bring home the bacon for their constituents at the expense of a rational and efficient allocation of resources.

Presidents, by contrast, are elected by the nation as a whole. This difference, it is argued, insulates presidents from parochial impulses and encourages presidents to pursue policies that benefit the nation as a whole, rather than a select few. If true, delegation to the president should produce superior policy outcomes. The future Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan made this very argument in a 2001 piece in the Harvard Law Review.

We argue that this logic is fundamentally flawed. It ignores the electoral, partisan, and coalitional forces that drive presidents, like members of Congress, to be particularistic: that is, to prioritize the needs and desires of some citizens over others when pursuing their agendas. By analyzing the allocation of more than $8.5 trillion of federal grants across the country from 1984 through 2008, we show that presidents have created systematic political inequalities in who enjoys the benefits of federal spending that dwarf those created by Congress.

Three incentives encourage presidents to be particularistic. First, presidents do indeed have a national constituency. However, voters do not directly choose the next occupant of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. Rather, the Electoral College does. Over the past thirty years, an increasingly small number of states have wielded disproportionate influence in selecting the next president. Presidents have strong incentives to target federal resources to court voters in swing states.

But presidents are more than just reelection-seekers. They are also partisan leaders. As such, presidents pursue policies that systematically channel federal dollars disproportionately to parts of the country that form the backbone of their partisan base.

Finally, to succeed legislatively, presidents must build coalitions. In contemporary politics, presidents have been forced to rely heavily, often almost exclusively, on co-partisans in Congress to advance their legislative agendas. To court favor on Capitol Hill and to maintain their party’s strength in Congress, presidents also have incentives to reward constituencies that elect co-partisans to the legislature with bigger shares of federal largesse.

Analyzing the geographic allocation of all federal grant dollars from 1984 through 2008, we find evidence of all three forms of presidential particularism. The result is massive presidentially induced inequalities in the allocation of federal dollars across the country.

Controlling for a host of factors that shape the amount of grant spending different parts of the country receive, we find that presidents systematically channel a disproportionate share of federal dollars to swing states. Our analysis shows that communities in swing states consistently receive more federal grant dollars than comparable communities in uncompetitive states. Moreover, presidents are particularly eager to court voters in swing states as the next election approaches. In presidential election years, constituencies in swing states receive even larger infusions of federal grant dollars.

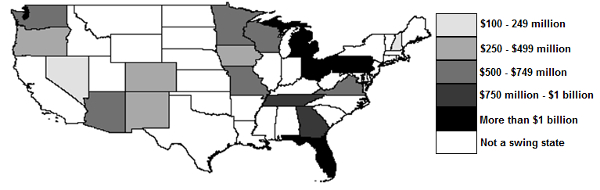

The sums are substantial. For example, the map in Figure 1 illustrates the estimated increase in grant spending that each swing state received in 2008 simply by virtue of being electorally competitive. In 2008, four pivotal swing states – Florida, Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania – received more than $1 billion in additional grant spending, by virtue of being swing states. Finally, our results show that in presidential reelection years, swing state targeting is at its peak.

Figure 1 – Estimated Increases in Grant Spending Secured by Swing States, 2008

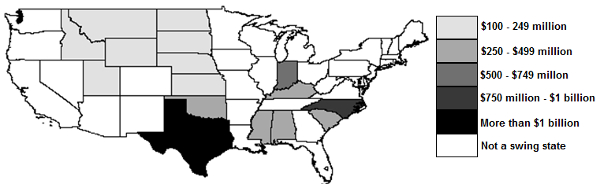

Presidents also look after their partisan base. Communities in core states – that is, states that reliably back the president’s party at the polls – also receive disproportionate shares of federal largesse. For large red and blue states, such as California and Texas, billions of dollars are on the line at each presidential contest. For example, the map in Figure 2 illustrates the estimated increase in grant spending that a number of states received in 2008 because they reliably backed the incumbent Republican Party, rather than the Democratic Party. Our model predicts that in 2008 Texas received $2 billion in additional grant spending by virtue of being a core Republican state. If John Kerry had won the 2004 race, Texas would have lost significant funds, while New York and California would have gained significantly.

Figure 2 – Estimated Increases in Grant Spending Secured by Core States, 2008

Finally, presidents also target federal dollars to constituencies that elect co-partisans to Congress. We find that the median county that sent a member of the president’s party to the House in the last election receives $8.6 million more in grant spending, on average, than a comparable county that voted for a member of the opposition party for Congress.

The political inequalities produced by these presidential particularistic forces dwarf those produced by congressional parochialism. Majority party members have some capacity to secure more federal grant dollars for their constituents. However, the magnitude of this effect pales in comparison to the advantages presidents secure for swing or core constituencies. Moreover, we find no evidence that members of key committees are systematically able to secure unequal shares of federal largesse for their constituencies.

On many policy questions, presidents undoubtedly bring a different, more national perspective than do members of Congress. However, electoral and partisan incentives result in presidents pursuing policies that generate significant political inequalities in the allocation of federal dollars across the country.

This article is based on the paper ‘Presidential Particularism and Divide-the-Dollar Politics’, in the American Political Science Review. The ideas in this blog post are developed further in their forthcoming book, The Particularistic President: Executive Branch Politics and Political Inequality.

Featured image credit: Truthout.org (CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1xWqXsp

_________________________________

About the authors

Douglas Kriner – Boston University

Douglas Kriner – Boston University

Douglas Kriner is an Associate Professor of Political Science and the Director of Undergraduate Studies at Boston University. His research interests include American political institutions, separation of powers dynamics, and American military policymaking.

_

Andrew Reeves – Washington University in St. Louis

Andrew Reeves – Washington University in St. Louis

Andrew Reeves is an assistant professor of political science at Washington University in St. Louis and a research fellow at the Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government, and Public Policy. His substantive interests focus on the interchange between institutions and behavior. Specifically, he studies electoral accountability of presidents and members of Congress.

80% of the states are not swing states.

Only 12 states received any attention in the 2012 general election campaign.

From 1992- 2012

13 states (with 102 electoral votes) voted Republican every time

5 states (56) voted R 5 times

7 states (61) voted R 4 times

2 states (38) voted D 3 times and R 3 times

19 states (242) voted Democratic every time

3 states (15) voted D 5 times

2 states (24) voted D 4 times

Some states have not been been competitive for more than a half-century and most states now have a degree of partisan imbalance that makes them highly unlikely to be in a swing state position.

States have the responsibility and power to make their voters relevant in every presidential election. The National Popular Vote bill uses the power given to each state by the Founders in the Constitution to decide how they award their electoral votes for president.

The National Popular Vote bill would guarantee the presidency to the candidate who receives the most popular votes in the country.

Every vote, everywhere, would be politically relevant and equal in presidential elections. No more distorting and divisive red and blue state maps of pre-determined outcomes.

The bill would take effect when enacted by states with a majority of Electoral College votes—that is, enough to elect a President (270 of 538). The candidate receiving the most popular votes from all 50 states (and DC) would get all the 270+ electoral votes of the enacting states.

The bill has passed 33 state legislative chambers in 22 rural, small, medium, large, red, blue, and purple states with 250 electoral votes. The bill has been enacted by 11 jurisdictions with 165 electoral votes – 61% of the 270 necessary to go into effect.

NationalPopularVote