Can teaching racial pride help to combat the discriminatory policies that see a disproportionate number of Black and Latino men incarcerated or killed by police? Megha Ramaswamy and Jessie Daniels offered an educational program to young Black and Latino men between the time they left jail and their return home, which included sessions on racial and ethnic pride. They found that, compared to those who did not take part in their program, after one year, participants had spent less time in jail and had fewer problems with drug dependence.

Can teaching racial pride help to combat the discriminatory policies that see a disproportionate number of Black and Latino men incarcerated or killed by police? Megha Ramaswamy and Jessie Daniels offered an educational program to young Black and Latino men between the time they left jail and their return home, which included sessions on racial and ethnic pride. They found that, compared to those who did not take part in their program, after one year, participants had spent less time in jail and had fewer problems with drug dependence.

In the wake of the death of Trayvon Martin in 2012, President Obama launched an initiative called My Brother’s Keeper to send the message the lives of young men of color matter.

One of the key ways to help Black and Latino young men thrive is through racial pride. This may sound counterintuitive in a world in which a majority of young people in a recent poll said they thought their generation was “post-racial.” Our research with young men leaving jail and returning home suggests just the opposite, that embracing racial and ethnic pride can really matter in ways that can help these young men protect themselves.

Based on our research in New York City jails in the last 15 years, we’ve found that workshops that focus on “racial pride” – teaching about historical antecedents to contemporary movements like #Black Lives Matter – offers a powerful shield against the discriminatory policies that result in the mass incarceration of black and brown bodies.

What we, and a team of colleagues, offered was a 30-hour educational program that served as a bridge between the young men’s time in jail and their return home. The eight sessions focused on a range of topics, including the political economy of the drug war, gender and sexual relationships, and a session on racial and ethnic pride called, “My people, my pride/ Mi gente, mi orgulla.” Half of the 552 people in the 5-year study participated in the educational program, and the other half got the usual discharge plan from jail. The focus on these young men, in particular, was driven by the complex intersections of masculinity, race, criminal justice status, and health.

The idea for an intersectional approach to this work came from previous research with young women. Researchers Gina Wingood and Ralph DiClemente (Emory University) began doing similar work with young African American girls. In workshops designed to reduce their risk of HIV/STDs, instead of focusing exclusively on the biology of disease transmission, they included material on black feminist heroines, like Sojourner Truth and Ida B. Wells. Their results were promising. They found a significant drop in risk for young girls who participated in the workshops versus those who did not. And, they made a compelling case for interventions that explicitly took gender and power into account. We wanted to replicate their work with young men who had been unlucky enough to land in jail at Rikers Island.

Our results were similar. When we followed up with the young men in our study a year later, we found that those who had participated in the educational program spent fewer days in jail compared with those who didn’t. We also found that they had fewer problems with drug dependence. When the young men had higher levels of racial pride at the time of their incarceration, they were significantly less likely to be reincarcerated or be engaged in illegal activities even up to one year after release from jail compared to men with lower levels of racial pride. The same young men were less likely to endorse violence to resolve conflict.

Other research with young people who haven’t been caught up in the legal system confirms the importance of racial pride as a protective factor against discrimination. Survey research of 630 mixed-gender adolescents from middle class backgrounds in 2013 by Ming-Te Wang (University of Pittsburgh) and James P. Huguley (Harvard University) found racial pride to be the single most important factor in guarding against racial discrimination, and discovered it had a direct impact on the students’ grades, future goals, and cognitive engagement.

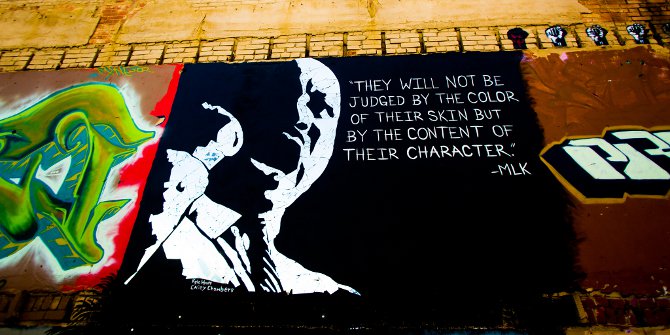

While we know that racial pride can be transformative, we also recognize its limitations. Racial pride is still no guarantee against death at the hands of the state or others, and the young men we worked with know this. When we piloted the workshop on ethnic pride, we showed the men photographs of civil rights leaders – Che Guevara, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King – and asked the young men what they thought when they saw these images. One telling response to the images: “These guys are cool, but they’re all dead.” This observation aside, most of the young men we encountered in jail had heard little in their traditional educational programs about what might make them proud of being African American or Latino, outside of limited “Black History Month” or “Hispanic Heritage” events. The young people we’ve met in jail are eager to learn about their history and taking pride in it made a difference for their lives.

It has been heartening, against a backdrop of police-perpetrated racialized violence in the U.S., to watch young people take to the streets to let their voices be heard and join social movements that challenge this type of violence. There is some evidence that lawmakers, prosecutors, and even President Obama continue to listen. We know that racial pride can be a source of strength and resilience but the true test is whether society can support such resilience.

This article is based on the paper ‘The Association of Ethnic Pride With Health and Social Outcomes Among Young Black and Latino Men After Release From Jail’, in Youth & Society.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1QXueNz

_________________________________

Megha Ramaswamy – University of Kansas School of Medicine

Megha Ramaswamy – University of Kansas School of Medicine

Megha Ramaswamy is an Assistant Professor of Preventive Medicine and Public Health at University of Kansas School of Medicine. Dr. Ramaswamy’s current work addresses the social context of sexual health risk among incarcerated women and is funded by the National Institutes of Health (National Cancer Institute) and American Cancer Society. The work described in this article was also funded by the National Institutes of Health (National Institute on Drug Abuse).

Jessie Daniels – City University of New York (CUNY)

Jessie Daniels – City University of New York (CUNY)

Jesse Daniels is Professor of Public Health, Sociology and Critical Psychology, at Hunter College, CUNY School of Public Health and The Graduate Center, CUNY. An internationally recognized expert on Internet manifestations of racism, Daniels is the author of two books about race and various forms of media, White Lies (Routledge, 1997) and Cyber Racism (Rowman & Littlefield, 2009), as well as dozens of peer-reviewed journal articles. She writes for, maintains and is co-founder of Racism Review, a scholarly blog.

1 Comments