An important part of the 2010 Affordable Care Act was the expansion of Medicaid – something which 30 states have taken up. In new research, Jeffrey Clemens finds that not only does expanding Medicaid benefit those who gain coverage; it may also help to improve the performance of Obamacare’s health insurance exchanges. Since those eligible for Medicaid tend to have higher than average health expenses than most on the exchanges, drawing these individuals out of the exchanges means lower premiums for those that use them, making them less likely to opt-out.

An important part of the 2010 Affordable Care Act was the expansion of Medicaid – something which 30 states have taken up. In new research, Jeffrey Clemens finds that not only does expanding Medicaid benefit those who gain coverage; it may also help to improve the performance of Obamacare’s health insurance exchanges. Since those eligible for Medicaid tend to have higher than average health expenses than most on the exchanges, drawing these individuals out of the exchanges means lower premiums for those that use them, making them less likely to opt-out.

The Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) effort to expand insurance coverage has many moving parts. Principal among them are Medicaid expansions, subsidies for plans purchased on states’ insurance exchanges, and community rating regulations. In recent research, I analyzed an under-appreciated link across these elements of the ACA’s approach to reducing the ranks of the uninsured.

By 2016, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that the ACA will reduce the number of uninsured individuals by 25 million. It expects 12 million, or just under half of these individuals, to gain coverage through Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). CBO’s estimates for 2014 include 6 million publicly insured and a net of 6 million privately insured, most with aid from subsidies.

To better understand how these provisions relate, I analyzed the experiences of states that implemented similar policies during the 1990s. The analysis reveals that typical projections provide an incomplete picture of Medicaid’s role. I find that exchange-based coverage may disappoint both consumers and policymakers in states that opt not to expand their Medicaid programs. Put differently, Medicaid expansions will tend to improve the performance of states’ exchanges.

High among the ACA’s goals is to increase the affordability of insurance for the sick. It seeks to do so through rules called community rating regulations, which prohibit insurers from adjusting premiums in response to pre-existing conditions. These rules reduce the premiums faced by the sick, but do so by increasing the premiums of the healthy. Consequently, they run the risk that the healthy will opt out of coverage, a phenomenon known as adverse selection. Policy analysts take this concern quite seriously, as shown by the anxious monitoring of the age, gender, and health mix of those enrolling in exchange-based coverage.

The ACA contains several provisions designed to combat adverse selection. Of these, the individual mandate is the most widely recognized. Those who forego coverage must pay a penalty, which makes remaining uninsured look less attractive. On the margin, these penalties thus shift the balance in favor buying coverage.

The second line of defense against adverse selection involves the subsidies targeted at low- and middle-income households. Subsidies directly reduce the cost of buying insurance. Like the mandate, they make getting coverage more attractive compared to remaining uninsured.

Medicaid expansions also combat adverse selection, although the channel through which they do so is more subtle. Premiums depend on the average health of exchange-based purchasers. If there are large numbers of unhealthy purchasers, premiums will be high, making plans a particularly bad deal for the young and healthy. The key insight is that Medicaid expansions typically improve the health mix of those seeking private coverage. Because health and income are strongly related, Medicaid-eligible individuals have higher average health expenses than most exchange-based purchasers. By drawing high cost individuals out of the exchanges, Medicaid expansions can reduce the severity of the adverse selection problem. Evidence from states’ experiences suggests that this link between Medicaid expansions and community rating regulations is quite important in practice.

In the early 1990s, several New England and Mid-Atlantic states enacted regulations similar to those in the ACA. Unfortunately, they initially did so without utilizing mandates, subsidies, and Medicaid expansions to combat adverse selection. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the initial performance of community-rated markets was quite poor. Coverage rates declined and comprehensive insurance policies became more difficult to obtain. Adverse selection pressures thus appear to have been quite severe.

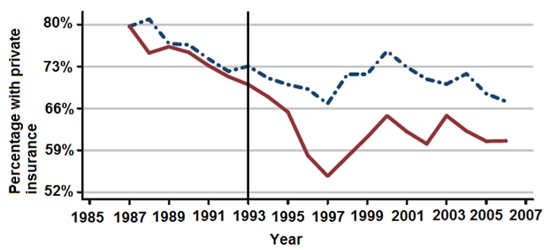

As Figure 1 shows, states that implemented community rating regulations (the solid red line) initially experienced declines in private coverage rates relative to other states (the dashed blue line). Over the next decade, however, their coverage rates rebounded substantially. An important pattern underlies these developments. Rebounds in private coverage were largest where Medicaid expanded most dramatically for the disabled, the medically needy, and other high cost populations.

Figure 1 – Percentage with private insurance across samples states

A simple cost comparison, using data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), illustrates why Medicaid expansions can have this effect. The ACA’s community rating regulations apply to insurance purchases made by small employers and by individuals on exchanges. In 2011, the health care costs of individuals obtaining insurance in these settings averaged $4,300. Among this group’s healthiest third, costs averaged $3,200. By contrast, the health care costs of non-elderly, adult Medicaid beneficiaries averaged $8,300. Notably, this is in spite of the relatively low rates Medicaid pays hospitals and physicians.

Imagine what would happen if current Medicaid beneficiaries were shifted onto the exchanges. The MEPS data imply that the average healthcare costs of exchange-based purchasers would rise by more than $1,000. This would significantly increase the premiums faced by the young and healthy, making them more likely to opt out of coverage. This same line of logic reveals how Medicaid expansions can work to reduce adverse selection and improve exchange-based coverage.

My findings highlight an important, under-appreciated link between Medicaid and the overall design of the ACA’s coverage expansion. Historically, Medicaid beneficiaries have averaged much higher healthcare costs than the privately insured. Covering such individuals through Medicaid can thus reduce the premiums prevailing on states’ exchanges. This makes exchange-based plans more attractive to the young and healthy, whose participation is essential for the system to work.

This insight casts new light on ongoing debates over states’ ACA Medicaid expansions. As of May 2015, 30 states (including Washington, DC) have implemented such expansions, 3 continue discussing their options and 18 have, for the time being, opted out. Most commentary emphasizes bottom-line numbers of beneficiaries whose eligibility rides directly on these decisions. My analysis highlights why the performance of the exchanges may also be at stake. Absent Medicaid expansions, exchanges are at increased risk of being saddled with high costs and, as a result, relatively severe adverse selection pressures. Well implemented Medicaid expansions hold the promise of relieving these pressures and improving exchange-based coverage.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Regulatory Redistribution in the Market for Health Insurance’, in the American Economic Journal: Applied Economics.

Featured image credit: Stephen Melkisethian (Flickr, BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post:http://bit.ly/1G0Xkbo

_________________________________

Jeffrey Clemens – University of California, San Diego

Jeffrey Clemens – University of California, San Diego

Jeffrey Clemens is an assistant professor in the department of economics at the University of California at San Diego (UCSD). He received his PhD in economics at Harvard University in 2011. Before moving to UCSD, Jeff spent one year as a postdoctoral fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. His recent research focuses primarily on topics in social insurance, with an emphasis on health care payment systems. Additional research interests include fiscal policy, state and local government finance, and drug control policy.