The traditional view of North American suburbs is that they are populated by those on relatively high incomes who own their single-family home. Mark Williamson and Robert Walter-Joseph report on a new study which challenges the established view of where suburban life is located. They write that by studying all of Canada’s 26 major metropolitan areas, researchers found many central city neighborhoods which exhibited high proportions of suburban-style living, as well as peripheral areas that had more urban characteristics. They write that ‘suburbanism’ is as much about where income is concentrated as it is about aspects of the built form. It is not solely about being outside a city center.

The traditional view of North American suburbs is that they are populated by those on relatively high incomes who own their single-family home. Mark Williamson and Robert Walter-Joseph report on a new study which challenges the established view of where suburban life is located. They write that by studying all of Canada’s 26 major metropolitan areas, researchers found many central city neighborhoods which exhibited high proportions of suburban-style living, as well as peripheral areas that had more urban characteristics. They write that ‘suburbanism’ is as much about where income is concentrated as it is about aspects of the built form. It is not solely about being outside a city center.

In both the US and Canada, gentrification, income polarization and the condo development boom since the 1980s have led to increasing socioeconomic diversity across our urban centres. We are seeing high-income residents moving back into the traditionally lower-income inner city at the same time as lower-income earners are moving to the suburbs.

These trends have renewed interest in the geography of income, as some have speculated that we will eventually see a complete reversal of the income structures of the past, with inner cities becoming much wealthier than their surrounding suburbs.

Much of the evidence for these trends is based on an understanding of the suburbs and inner city as distinct and separate places. But given the increasing complexity of neighborhoods, this dichotomy is unable to capture the diversity contained in the suburbs. In a recent study, Canadian researchers Markus Moos at the University of Waterloo and Pablo Mendez at Carleton University created a complementary definition of the suburbs based on the characteristics – or ‘ways of living’ – in the places where people reside, rather than just the geographic location. Based on this definition, they ask whether there is in fact a diversity of income in suburban ways of living. They find that higher income households are spreading to new parts of the city, bringing suburban ways of living to unexpected locations and redefining the meaning of contemporary suburban living.

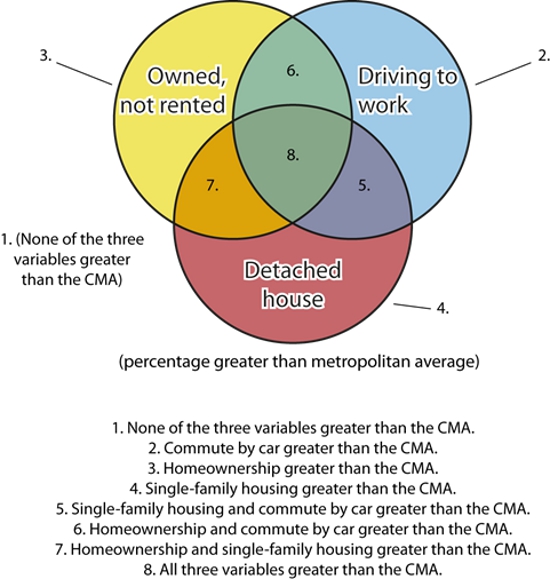

But what exactly is meant by a ‘suburban’ way of living? The researchers operationalize the concept through three key dimensions: built form, tenure type and commute mode. The popular image of the suburban lifestyle, as well as the scholarly perspective, is generally associated with high proportions of single-family dwellings, homeownership and automobile use.

Using census data at neighborhood level geographies, eight categories of neighborhoods were created based on various combinations of the three dimensions. Categories are based on their relation to the metropolitan average for each variable, with an above average score indicating a higher degree of suburbanism. Figure 1 shows the eight neighborhood types, ranging from least (Category 1: areas that fall below metropolitan averages on all indicators) to most suburban (Category 8: areas that exceed metropolitan averages on all indicators).

Figure 1 – Neighborhood categories

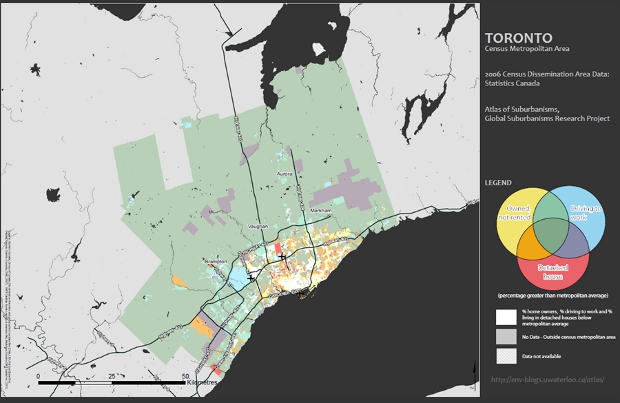

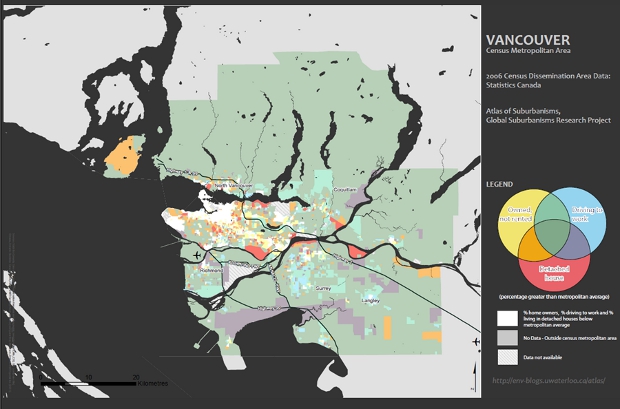

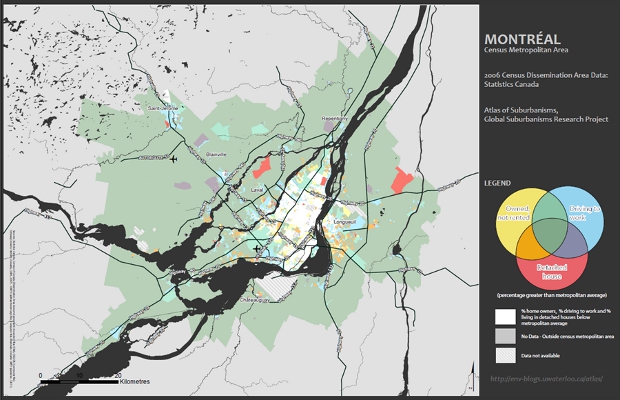

Maps of these categorizations provide a picture of where suburban ways of living are most prevalent. This is available for all 26 major metropolitans areas in Canada, but only the largest are shown here (see Figures 2 through 4).

Figure 2 – Toronto

Figure 3 – Vancouver

Figure 4 – Montreal

A few things are apparent from this analysis. First, the size of the suburban population in the Canadian metropolitan system is substantial. In all of the metropolitan areas studied, between 32 to 55 percent of the population lived in Category 8 suburbs. But at the same time, 13 to 33 percent lived in the Category 1 areas (the most urban), suggesting there is a degree of polarization occurring in the types of places we live in, with few people living in the neighborhoods that are neither fully suburban nor fully urban.

Second, high rates of homeownership occur throughout the metropolitan landscape, not only in peripheral areas. In case study cities, homeownership grew from 56 to 65 percent between 1981 and 2006. Interestingly, a large share of this growth occurred in the inner city, where intensification, gentrification and ‘condofication’ have led to what have sometimes been called ‘vertical suburbs.’ This is not meant to overstate this relatively recent manifestation of downtown suburbanism, however: the neighborhoods within ten kilometres of the central business district still had the lowest ownership rates in 2006.

Finally, the maps show a high degree of complexity and spatial variability in the suburbanisms studied. There are central city neighborhoods exhibiting high proportions of suburban ways of living and also peripheral areas that are more urban than the metropolitan average. This suggests that defining suburbs based on distance from the centre may not be the best approach to capture how suburban ways of living relate to actual locations in the metropolitan landscape.

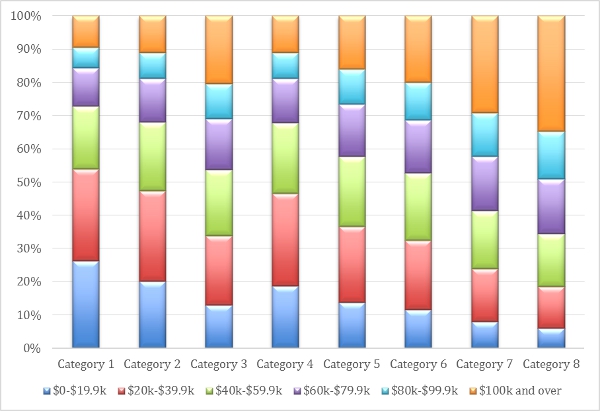

So the location of suburbanisms is complex, occurring both downtown and within the periphery, but are suburban ways of living correlated with income? Figure 5 shows a clear gradient in household income across the eight categorizations. Regression results find that all the built form/tenure/commute variables are correlated with income. Category 8 neighborhoods – the most suburban – show the largest statistical association, indicating that the combination of the three suburbanism indicators together explains more about where income is concentrated than each of these variables on their own.

Figure 5 – Distribution of pre-tax household income bracket by suburbanism category

Source: Calculated using Statistics Canada data, 2007 (2006 Census). Adapted from: Moos, M. & Mendez, P. (2014). Suburban ways of living and the geography of income: How homeownership, single-family dwellings and automobile use define the metropolitan social space. Urban Studies, pp. 1-19.

Categories 3, 6 and 7 have the next highest explanatory power in most of the metropolitan areas studied. The common denominator in all of these groups is higher than average homeownership rates. This indicates that tenure explains more about where income is concentrated than either of the other two variables. While this may seem like an intuitive link, it is an important finding when considering the broad dispersal of homeownership evident in the maps. Higher-income households are spreading to new geographies, including the inner city, via ownership tenure.

In comparing findings between metropolitan areas, the size and economic structure of the city is important. In most of Canada’s largest urban centres (Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, Calgary), the relationship between suburban ways of living and income is much weaker than it is in smaller metropolitan areas and those that are more economically dependent on their manufacturing sector. In large post-industrial cities, gentrification and downtown revitalization through condo development have drawn wealthy households into the inner city and undermined the traditional suburban-affluence connection.

From a policy perspective, there are important implications in these findings. Despite claims that suburbs are becoming more diverse in terms of their socioeconomic composition, this research suggests that across 26 distinct metropolitan areas, suburban ways of living remain consistently associated with higher incomes. Yet suburbanization, as defined by Moos and Mendez, no longer only means living at the urban fringe, nor does it suggest a complete reversal of traditional patterns: in the contemporary metropolitan landscape, suburban ways of living, and homeownership in particular, are prevalent both at the periphery and in the central city.

The strong association between homeownership and higher incomes – and conversely renting and lower incomes – suggests that the continued promotion of ownership in housing policy comes at the expense of less affluent residents. This problem is particularly acute in urban revitalization and intensification efforts, which can result in a marginalization or displacement of lower-income renters. Possible responses include public reinvestment in the rental sector, the promotion of cooperative housing, or requirements on new condominium developments to include a share of low-income housing units. By directly considering the relationship between housing tenure and affluence, these policies could help stem potential displacement and allow access to central city living for a wider range of incomes.

Finally, this analysis should remind North American policymakers and researchers of the limitations of defining the suburbs as a geographically fixed ‘place’. While distance from the city centre does explain a lot about where suburbanism is occurring, the researchers also find a wide range of suburban and urban ways of living occurring in unexpected locations throughout the metropolitan landscape. Suburbs are not homogeneous landscapes but rather, they contain particular patterns of living that may be associated with particular forms of housing, tenure and commuting patterns. The empirical method developed by Moos and Mendez provides an opportunity to look beyond mutually exclusive spatial entities and consider a complementary approach to understanding the geography of suburban ways of living.

Featured image credit: Evan Leeson (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

This article is based on the paper, ‘Suburban ways of living and the geography of income: How homeownership, single-family dwellings and automobile use define the metropolitan social space’, in Urban Studies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of U.S.App– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1HXOZ5U

_________________________________

Mark Williamson – University of Waterloo

Mark Williamson – University of Waterloo

Mark Williamson is a student in the School of Planning at the University of Waterloo and a research assistant on Professor Markus Moos’ Generationed City research project.

Robert Walter-Joseph – University of Waterloo

Robert Walter-Joseph – University of Waterloo

Robert Walter-Joseph is a graduate of the Master’s of Planning program at the University of Waterloo and a research assistant with Professor Markus Moos.