For many adolescents experimenting with drugs is a fairly normal part of growing up, but many are accessing these drugs at, or near to, schools. In new research, Dale Willits, Lisa Broidy, and Kristine Denman find that drug crime is higher in city blocks that have middle and high schools. They write that schools give drug dealers and buyers the opportunity to meet, a process that occurs regardless of the neighborhood’s characteristics.

For many adolescents experimenting with drugs is a fairly normal part of growing up, but many are accessing these drugs at, or near to, schools. In new research, Dale Willits, Lisa Broidy, and Kristine Denman find that drug crime is higher in city blocks that have middle and high schools. They write that schools give drug dealers and buyers the opportunity to meet, a process that occurs regardless of the neighborhood’s characteristics.

According to the Centers for Disease Control in 2013, over one-in-five high school students are offered, sold, or given an illegal drug by someone on school property. This is not surprising. Adolescence is the period when most people first experiment with illegal drugs. Given the primary role of schools in the lives of adolescents, we would certainly expect that this environment plays centrally in adolescent drug use. Experimenting with drugs is fairly normal during adolescence and, unless this experimentation starts early or advances to chronic use, it is generally not associated with long term negative outcomes. At the same time, that adolescents are accessing drugs at school suggests a drug sales and distribution network in and around schools that could have deleterious consequences for the surrounding neighborhood. Indeed, criminological research suggests that schools can generate crime in the surrounding neighborhood, and this may be linked to the drug networks adolescents are accessing in and around schools.

From a theoretical perspective, the school-neighborhood crime link can be at least partially explained by the routine activities perspective. From this perspective, crime is most likely when motivated offenders converge with suitable victims in places with low levels of guardianship. Schools provide such an environment. In the case of drug crime, the demographics of the population mandated to attend high school overlaps considerably with the demographics of the population most likely to sell and purchase illegal drugs (young people between the ages of 16 and 24). And while schools have guardianship in the form of teachers, school administrators, security guards, and increasingly, law enforcement officers, students (the population of potential offenders and victims) vastly outnumber these guardians, especially as student teacher ratios continue to expand. This limits the effectiveness of guardianship in and around schools.

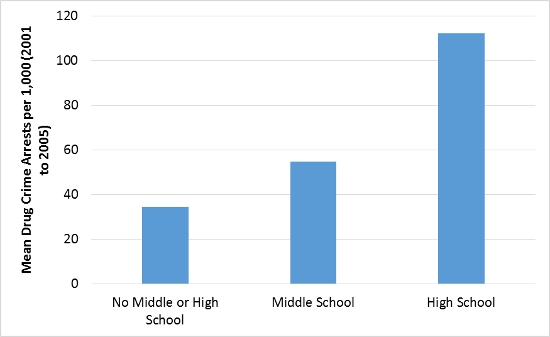

In recent research we looked at the link between schools and drug crime. We examined drug crimes in the 432 census block groups in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Our measure of drug crime included the total number of drug possession and distribution arrests made in each block group in Albuquerque between 2001 and 2005. After assembling these data, we examined drug offense rates for block groups based on whether the block group contained a middle school and/or a high school. Our findings confirmed that block groups containing middle schools and block groups containing high schools have substantially higher rates of drug crime than block groups without schools. As Figure 1 shows, this relationship is strongest in neighborhoods with high schools, where the population of potential offenders and victims is highest and levels of guardianship lowest.

Figure 1 – Drug Offenses by Block Group Type

This pattern persists even after accounting for a variety of other variables correlated with drug crime, including composite measures of poverty, residential instability, and the demographic make-up of the block groups. Indeed, block groups with middle schools and high schools report heightened levels of drug crime regardless of the social and economic characteristics of the block group. This result is quite important, because it suggests that schools facilitate neighborhood drug crime in both poor and affluent neighborhoods. This means that schools override some of the neighborhood level protective factors that work to reduce crime in more affluent neighborhoods.

The routine activities argument can be extended beyond a discussion of where crime occurs to a discussion of when crime occurs. If schools facilitate drug market activity by promoting the convergence of offenders and victims, then the school effect should be greatest during time periods when this convergence actually occurs. These time periods include the morning commute to school, school hours, and the afternoon commute away from school. In additional analyses, we found that this is in fact the case. The difference in drug crime between block groups with and without middle and high schools was greatest during the periods when students are at school and commuting to and from school.

Figure 2 – Drug crimes during non-school, school, and school commute hours

Figure 2 above shows this result for high schools, with block groups containing high schools highlighted by the dark borders. The Non-School Session map shows drug crime counts during time periods when schools are not likely to facilitate illicit drug transactions. This includes crimes that occur during late afternoon, evening, weekend, and summer hours. The School Session map displays drug crime counts for all incidents occurring during the morning commute, school day, and afternoon commute hours. In the Non-School Session map, several of the block groups (especially those in the more affluent northeast heights section of Albuquerque) have very few incidents. Conversely, in the School Session map, each block group containing a school is a darker shade on the map, indicating higher levels of narcotics crime. Further analyses show these differences to be both significant and substantial.

As a whole, the evidence suggests that schools facilitate neighborhood drug crime by providing the appropriate opportunity structure for drug dealers and buyers to meet in time and space. This process occurs regardless of neighborhood level characteristics that otherwise offer some protection from crime. Though schools bring a range of benefits to a neighborhood, they also introduce some risk. All neighborhoods need to be mindful of these potential risks and consider ways to mitigate them for the benefit of both the students and the broader neighborhood.

This article is based on the paper ‘Schools and Drug Markets: Examining the Relationship Between Schools and Neighborhood Drug Crime’, in Youth & Society.

Featured image credit: Metro Centric (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1JGD3IG

______________________

Dale Willits – Washington State University

Dale Willits – Washington State University

Dale Willits is an Assistant Professor at Washington State University in the Criminal Justice & Criminology Department. His research interests explore issues related to policing (police organizational structure, policing outcomes, and policing data), the etiology of crime, juvenile delinquency, and the relationship between place and crime.

Lisa Broidy – Griffith University

Lisa Broidy – Griffith University

Lisa Broidy is an Associate Professor and Deputy Head of School (Research) at the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Griffith University. Her research interests include developmental and life course criminology, gender and crime/female offending criminological theory, and crime policy evaluation specifically around domestic violence and offender re-entry.

Kristine Denman – University of New Mexico

Kristine Denman – University of New Mexico

Kristine Denman is the Director of the New Mexico Statistical Analysis Center. She has 20 years of experience in both research and evaluation. She has led numerous criminal justice related projects for various agency partners at the city, state and federal levels. She has particular interest in the evaluation of criminal justice initiatives and issues surrounding offender re-entry.