On Friday last week, the Republican House Speaker, John Boehner, announced that he would resign at the end of October. Matthew Green writes that Boehner’s forthcoming departure is symptomatic of larger forces that have made the job of Speaker extremely challenging.

On Friday last week, the Republican House Speaker, John Boehner, announced that he would resign at the end of October. Matthew Green writes that Boehner’s forthcoming departure is symptomatic of larger forces that have made the job of Speaker extremely challenging.

The Washington political community was caught unawares when John Boehner (R-OH), Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, announced on Friday that he would resign as Speaker before his two-year term had expired. Why would Boehner leave one of the highest positions in American government, one to which he had long aspired?

The conventional wisdom is that Boehner’s premature departure was due to a sizeable faction of conservatives within his party that has made his life difficult, refusing to provide the votes he needs to pass legislation and repeatedly calling for his removal as Speaker. But as I have argued elsewhere, this explanation, while correct, is too narrow. It neglects the ways in which Boehner’s resignation is symptomatic of larger political forces in the U.S. House – forces that have been at work for at least three decades and have made the Speakership one of the least safe and most difficult leadership jobs in Washington.

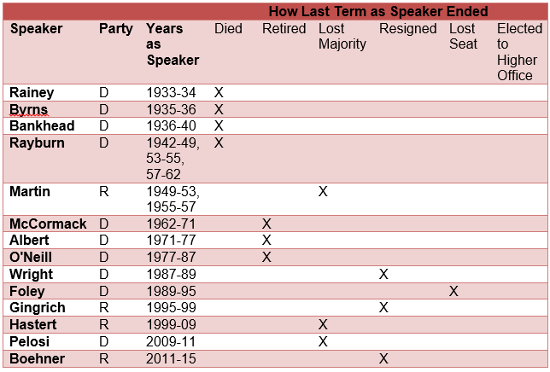

How unsafe is it? The table below shows how speakers since 1933 have ended their reign. Between 1933 and 1987, most speakers either retired at the end of a two-year term in the House or died while serving as Speaker. This career-like nature of the Speakership was, according to the political scientist Nelson Polsby, evidence that the House had institutionalized by the mid-20th century.

Table 1 – How House Speakers’ Tenure Ended, 1933-2015

But in recent decades, speakers have found the job a lot less secure. In fact, every Speaker since 1987 has either been compelled to quit or been forced out by voters. The Speakership, in other words, moved from a “career” model to a “revolt and rejection” model in which service is usually cut short by unhappy voters or disgruntled lawmakers.

There are several reasons for this, but two have been particularly significant. The first is that competition over control over the House has increased dramatically. This means a greater likelihood that today’s majority party will be tomorrow’s minority, and one Speaker will be replaced with another (as happened in 1994, 2006, and 2010). It also encourages minority parties to go after speakers, looking for ways to weaken them politically, tarnish the majority party’s reputation, and perhaps even encourage their resignation (as happened to two speakers, Jim Wright (D-TX) and Newt Gingrich (R-GA)).

The second reason is that at least one party, the GOP, has periodically suffered from internal divisions, often more tactical than ideological, with at least one faction dissatisfied enough to push for the removal of the Speaker. Gingrich and Boehner faced uprisings within their ranks, and while neither was forcibly removed, both were left politically damaged and suffered considerable grief in trying to unify their parties.

It’s way too soon to tell whether these same forces will hamper the next Speaker of the House, though the odds are high they will. Nonetheless, looking further back in American history suggests an interesting pattern that might portend a change in this model of the Speakership in the not-too-distant future.

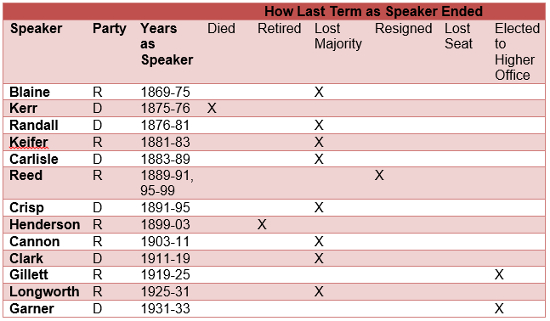

Table 2 below shows how Speakers of the House between 1869 and 1933 have ended their careers. It suggests two additional historical periods of Speaker tenure. The first, from 1869 until 1903, was somewhat similar to the current era: most speakers lost their jobs when their party lost control of the House. (Also, though only Thomas Reed (R-ME) resigned, arguably David Henderson (R-IA) did the same, since he abruptly chose not to run for reelection when faced with the possibility that a private indiscretion would go public.) This was also a period of greater competition for control of the House and, interestingly, a period of heightened partisan voting in Congress, much like today.

Table 2 – How House Speakers’ Tenure Ended, 1869-1933

In the next era, lasting from 1903 until 1933, Speakers also often lost their jobs due to switches in party control, but arguably their office followed more of an “up or out” model, with some speakers getting elected to higher office. Nowadays the Speakership is usually seen as the end of one’s career in public office, but in the past it was more reasonable for speakers to want to seek another political office. (Two Speakers in this era, Joe Cannon (R-IL), and Champ Clark (D-MO), made serious but short-lived runs for president).

In the next era, lasting from 1903 until 1933, Speakers also often lost their jobs due to switches in party control, but arguably their office followed more of an “up or out” model, with some speakers getting elected to higher office. Nowadays the Speakership is usually seen as the end of one’s career in public office, but in the past it was more reasonable for speakers to want to seek another political office. (Two Speakers in this era, Joe Cannon (R-IL), and Champ Clark (D-MO), made serious but short-lived runs for president).

Note that each of the first three historical periods lasted roughly the same length of time: between 30 and 45 years. This may be entirely coincidental, and as every stock prospectus warns potential investors, past performance does not guarantee future results. But if today’s Republicans find a way to unify their ranks soon and maintain their hold on the House for a while, it could eventually have an effect on the Speakership. Regardless, it is intriguing to consider whether, as we reach the 30-year mark since the last Speaker of the previous era, we may soon see a new – and perhaps more secure – era of Speaker leadership.

Featured image, House Speaker John Boehner Credit: Speaker John Boehner (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1QJVJJp

_________________________________

Matthew Green – The Catholic University of America

Matthew Green – The Catholic University of America

Matthew Green is an associate professor of politics at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. He is the author of The Speaker of the House: A Study of Leadership, which examines the motivations and consequences of legislative leadership by Speakers of the House since the 1940s. His most recent book, Underdog Politics: The Minority Party in the U.S. House of Representatives, explains the politics of the House minority party and the party’s influence on politics and policy since the 1970s.