The average delay between an executive nomination and confirmation by the US Senate is 120 days, but some nominees can experience delays of more than 400 or 500 days. In new research which examines over 8,000 bureaucratic nominations over 25 years, Ian Ostrander finds that nominations are targeted for delay based on their policy value, public importance, and the perceived ideology of the agency in question. For example, important agencies with low public importance, such as the Federal Election Commission, are often targeted by Senators for nomination delays.

The average delay between an executive nomination and confirmation by the US Senate is 120 days, but some nominees can experience delays of more than 400 or 500 days. In new research which examines over 8,000 bureaucratic nominations over 25 years, Ian Ostrander finds that nominations are targeted for delay based on their policy value, public importance, and the perceived ideology of the agency in question. For example, important agencies with low public importance, such as the Federal Election Commission, are often targeted by Senators for nomination delays.

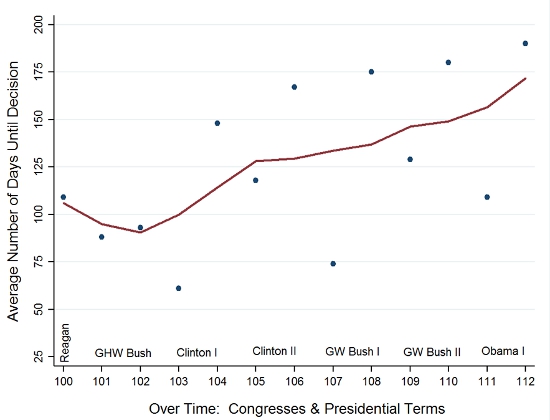

The US Senate does not have a reputation for rapid action, and the pace at which it evaluates and confirms presidential nominations to fill the highest levels of the American bureaucracy is no exception. In fact, the crippling delay of executive nominations to bureaucratic posts has become a common occurrence in US politics and has even caused the shutdown of a key agency. Relying upon an increasingly “do nothing” Congress, it may be no surprise that Presidents have become frustrated with the slowing pace of confirmation shown in Figure 1. However, evidence suggests that nominations are not simply casualties of a lethargic legislature; rather some nominations are targeted for obstruction based on a partisan strategy of denying presidents influence over bureaucratic decision-making.

Figure 1 – Nomination Delay within Congresses & Presidential Terms

Note: Data include over 8,000 cases coded from http://thomas.loc.gov/home/nomis.html. The included trend line is a Lowess smoother.

By strategically targeting delay, the effects of obstruction become more potent. While the average delay may be just over 120 days within a given Congress, an individual nominee may experience delays of over 400 or 500 days. In the face of such significant obstruction, nominees may simply decide to quit. Furthermore, at the end of every Congress, unconfirmed nominations fail automatically and must be re-nominated. When long delays are clustered within a particular agency, it leads to high vacancy rates that can change the character and capacity of an organization as it continues to operate without a full complement of officials.

Why are some nominations obstructed while other, seemingly similar nominations proceed without difficulty? When partisan delay is the motive, some nominations are worth far more than others. In new research looking at over 8,000 bureaucratic executive nominations between 1987 and 2012, I find support for the expectation that nominations are targeted for delay based on their policy value, public salience, and agency characteristics such as perceived ideology.

Perhaps the most valuable nominations to obstruct are those to major independent regulatory commissions like the National Labor Relations Board or the Federal Election Commission. Such commissions typically have a small board of about five members with both quorum requirements (meaning three of five board members must exist in order to make rulings) as well as party balancing rules ensuring that no one party can control an entire board. Because of their small size, influencing even just one board member can have a dramatic effect on the outcomes of board decisions. As such, these posts are critical.

Another closely related consideration is public attention. Few people are interested in the appointment of independent regulatory commissioners while many people care about cabinet-level appointments such as the Secretary of Defense or an Attorney General. While cabinet secretaries may thus seem like the ideal targets of delay, such positions are in part protected from obstruction by their very notoriety. Presidents are much more willing to engage in public appeals in order to further a cabinet secretary’s nomination in ways that they are not likely to do for a lower level position. Similarly, Senate leaders are more inclined to spend valuable floor time working towards the confirmation of a more salient position. As such, positions of low public salience are more likely to face obstruction.

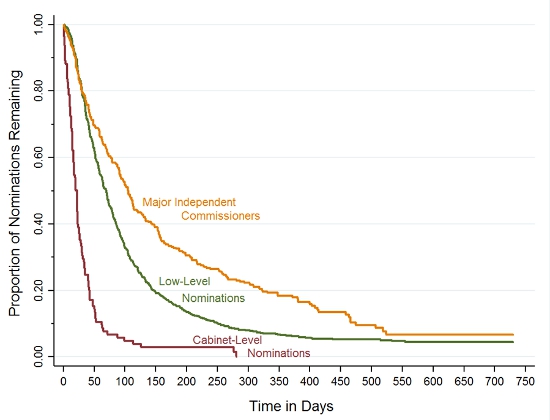

Figure 2 shows the proportion of nominations remaining unconfirmed in the Senate by how many days have passed since a nomination has occurred. These results are divided by the level of an appointment with just major independent commissioners, low-level nominations, and cabinet-level nominees shown. The results demonstrate that major independent commissions do in fact take the most time to confirm (with about 20 percent remaining unconfirmed after 350 days) while cabinet-level nominations are the fastest (with nearly all nominations complete after 150 days). Low-level appointments, with neither much public attention nor policy influence, are in between these two more extreme cases.

Figure 2 – Delay by Level of Appointments between 1987 and 2012

Note: Cases coded by author from http://thomas.loc.gov/home/nomis.html. Curves represent Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival rates for each given appointment tier.

Agency ideology is also an important consideration. When a position is vacant within an executive bureaucracy, that role is often filled by a career civil servant. As bureaucracies tend to develop their own cultures over time, they may also develop a reputation as being either more conservative or liberal ideologically. For example, the Environmental Protection Agency is viewed as liberal while the Department of Defense tends to be viewed as more conservative. Knowing these pre-dispositions, presidents will often try to control these biases by placing more appointees within agencies of the opposite ideology. Within my study, I also find that opposition senators tend to counter this strategy by obstructing nominations to their allied agencies in order to thwart presidential control.

Combined, these findings suggest that opposition party members within the Senate are targeting a president’s nominees for obstruction in order to achieve policy gains. By keeping a president’s nominees off of major commissions and by protecting allied agencies from presidential influence, senators may divert the stream of agency policymaking towards their own ideal. Such power, however, is not absolute. High salience positions are less likely to face crippling delay. As such, senators target vulnerable nominees who have policy relevance but little public salience. By targeting these mid-level nominees, the agencies are not so much headless as “neck-less.”

Given these levels of partisan obstruction, it is perhaps no surprise that in 2013 the Senate used the “Nuclear Option” in order to change the rules to make obstruction more difficult. However, because there is simply not enough time within a Congress to overcome obstruction on every nomination, Senate leaders will still be forced to prioritize nominations. As such, the inter-branch battle over executive nominations is expected to continue for the foreseeable future.

This article is based on the paper, ‘The Logic of Collective Inaction: Senatorial Delay in Executive Nominations’, in American Journal of Political Science.

Featured image credit: Ash Carter (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1JUxnHK

_________________________________

Ian Ostrander – Texas Tech University

Ian Ostrander – Texas Tech University

Ian Ostrander is an assistant professor of political science at Texas Tech University. His work generally involves the interaction between the US President and Congress with a particular interest in the politics of the executive nominations process. Recently, his work has appeared in the American Journal of Political Science and Presidential Studies Quarterly.