Our understanding of how Congress works has been shaped by the laws it enacts. But what about the laws which it repeals? In new research, Jordan M. Ragusa and Nathaniel A. Birkhead develop a comprehensive database of major Congressional repeals over more than 130 years. They find that repeals ‘spike’ when the majority party is united, and after it comes to power after a long time in the minority, such as in 1994’s ‘Republican revolution’.

Our understanding of how Congress works has been shaped by the laws it enacts. But what about the laws which it repeals? In new research, Jordan M. Ragusa and Nathaniel A. Birkhead develop a comprehensive database of major Congressional repeals over more than 130 years. They find that repeals ‘spike’ when the majority party is united, and after it comes to power after a long time in the minority, such as in 1994’s ‘Republican revolution’.

Our understanding of Congress—and how we evaluate the institution—is shaped by the laws it enacts. Indeed, some of the most cited and influential studies in the congressional literature over the past 30 years use law creation as their key construct. But even casual observers know that Congress often performs the opposite action: repealing landmark laws. But despite the regularity and importance of repeals, we know very little about when and why repeals happen.

One reason for the lack of research on repeals is methodological. Unlike lists of bills voted on or laws enacted, no government publication catalogues repeals. In new research, however, we describe a new dataset of major congressional repeals from 1877-2012. For this project we catalogued repeals by culling historical newspapers, historical reference volumes, and period-specific texts. In this respect, our work follows David Mayhew’s (1991) pioneering research on the passage of landmark laws.

Although the roots of this project began with a paper published in 2010, the topic was elevated in 2011 when Republicans took control of the House and promised to repeal the Affordable Care Act (a.k.a. “Obamacare”). Like the effort to repeal the Affordable Care Act, the repeals in our dataset represent some of the most contentious, salient, and long-running disputes over national policy. Examples include the repeal of multiple New Deal statutes following the 1994 Republican Revolution, dramatic statutory changes in monetary policy in the 1890s, the repeal numerous tax statutes in the 1920s, and the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Acts in the 1940s.

Beside the fact that they are understudied, repeals provide congressional researchers a unique perspective on Congress. Analytically, repeals allow us to compare lawmaking in two time periods: the enacting Congress and the repealing Congress. And theoretically, one of our central claims is that the causes of repeal differ from those which explain law creation. In particular, we believe that although shifts in Congress’s membership—known as changing “pivot points” in the literature—are a key cause of law creation, we believe the ebb and flow of party strength is critical to explaining law reversal.

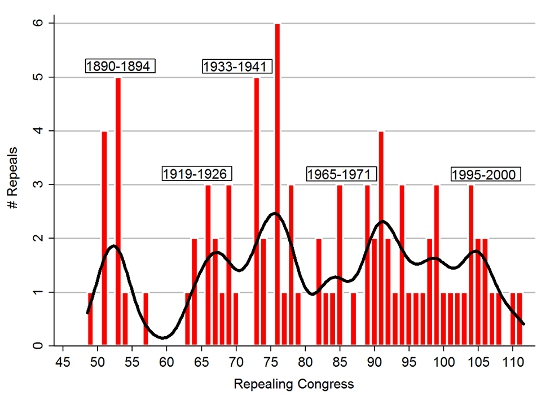

Figure 1 below presents our data. We can see that repeals do not occur uniformly over time: there are clear “spikes” in repealing activity. In brief, the spikes are generally consistent with our theoretical claims. We see increases in repealing activity when (1) the majority party is ideologically unified and (2) the majority came into power after a long stint in the minority.

Figure 1 – Congressional repeals 1877 – 2012

But because there are other factors that can cause repeal, we developed a statistical model that predicts when repeals happen. Our specific model is known as a “survival analysis.” Survival analysis is frequently used in epidemiology to understand how long patients survive some illness and the effects of surgical procedures and drugs. In the context of our study, the model predicts how long laws “survive” before being repealed.

Our model shows that some of the “usual suspects” explain when and why repeals happen. When the enacting coalition is voted out of office over time, and the distribution of preferences shift to the left or right, repeals are more likely to occur. We also find that the larger the distance between the House and Senate, the less likely repeals are to happen. Both findings fit well-established conclusions in the congressional literature regarding the creation of laws. We also find that repeals are more likely in two policy domains. First, tax laws are among the most likely to be repealed. And second, laws created for war purposes are often repealed soon after the war ends.

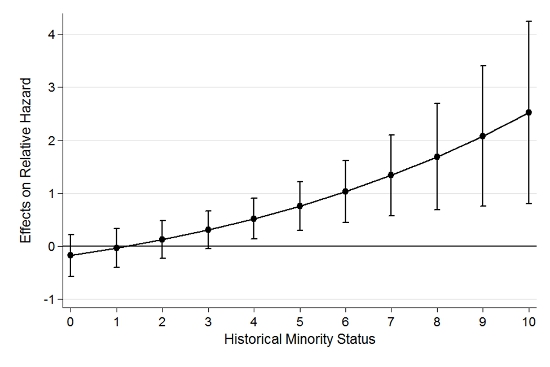

Although these findings help us understand when repeals are most likely, we find that the partisan factors in our model have the greatest overall effects on the probability of repeal. Like the descriptive results in Figure 1, the model reveals that repeals are most likely when the majority party is ideologically unified and the majority came into power after a long stint in the minority. We also find that these two effects are not just additive, but instead have an interactive effect. Figure 2 presents this interaction effect. On the x-axis is the measure of how long the majority was in the minority prior to winning control of the House and Senate (coded as the number of chambers in the minority over the past 10 years). The y-axis represents a higher or lower likelihood of repeal. And the dots represent the estimated effect of the majority party’s ideological cohesion.

Figure 2 – Influence of party minority status on likelihood of repeals

Figure 2 shows that when the majority party was in the minority for an extended time, and members of the majority are ideologically unified, there is an increased likelihood of repeal beyond what is predicted by these factors individually. As an example, when Republicans regained control of the House and Senate in 1995 after being the so-called “permanent minority,” a standard deviation increase in their ideological cohesion is predicted by the model to have increased the probability of repeal by 208 percent. And indeed, the Republican controlled congresses from 1995-2000 enacted a number of major repeals (most notably, the repeal of Glass-Steagall). At the other extreme, Figure 2 shows that when the majority has been in complete control of both chambers over the past decade (coded as zero chambers in the figure), there is no effect of greater ideological cohesion.

While there are various ways in which statutes can be “undone” (invalidation by the Supreme Court, defunding, sunsets, etc.), Congress regularly voids its own statutes via repeals. Given our findings about the importance of political parties to when and why repeals happen, in particular the ebb and flow of party strength, we characterize repeals as long-term contests between two great “teams” over national policy. Simply put, when Congress enacts a new law, it is hardly the end of the game. Anyone observing Republican attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act will recognize this feature. However, our results suggest that these kinds of partisan contests are an enduring feature of our politics.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Parties, Preferences, and Congressional Organization Explaining Repeals in Congress from 1877 to 2012’, in Political Research Quarterly.

Featured image credit; NOBama NoMas (Flickr, CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1VVMoju

_________________________________

Jordan Ragusa – College of Charleston

Jordan Ragusa – College of Charleston

Jordan Ragusa is an assistant professor of political science at the College of Charleston. His research and teaching interests are in the fields of American politics and institutions, political behavior, political economy, empirical theory, and research methodology. For more information, visit his research page. In addition to his academic writing, Ragusa is also the co-author of the American politics blog Rule 22 and is a regular contributor at the Christian Science Monitor.

Nathaniel A. Birkhead – Kansas State University

Nathaniel A. Birkhead – Kansas State University

Nathaniel Birkhead is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Kansas State University. His research interests focus on primarily on representation, legislative elections, and legislative behavior, with an emphasis on state legislatures. Aside from these research interests, other projects include an analysis of the ideological and socioeconomic characteristics of party activists and an evaluation of differences between state and national political parties.

2 Comments