Modern political discourse is dominated by ‘extreme’ media commentators such as Glenn Beck, Keith Olbermann, and Sean Hannity. But could these bombastic hosts actually be good for US democracy? In new research using experiments and survey data, J. Benjamin Taylor finds that rather than misinforming people, watching extreme media is linked to improvements in people’s political knowledge.

Modern political discourse is dominated by ‘extreme’ media commentators such as Glenn Beck, Keith Olbermann, and Sean Hannity. But could these bombastic hosts actually be good for US democracy? In new research using experiments and survey data, J. Benjamin Taylor finds that rather than misinforming people, watching extreme media is linked to improvements in people’s political knowledge.

Is it possible that hosts like Sean Hannity and Rachel Maddow are good for American democracy? Do they, while providing news in their bombastic and entertaining way, help viewers learn about politics? In short, yes, extreme media do increase political knowledge, which is counterintuitive given the prevailing discussion about these media outlets and personalities.

‘Extreme media’ are sometimes called ‘outrageous media’ because they use outrage and bombast to make their points and present information on television. The best examples are Glenn Beck, Keith Olbermann, and Sean Hannity. I use the term ‘extreme’ because there is something more than just bombast to these hosts. Compared to the most mainstream news sources in American—nightly broadcast news or PBS—these hosts are clearly extreme both in terms of content and bombast.

A key issue to consider is what, exactly, is wrong with these media? Reports frequently suggest that people who watch these shows know less that other Americans. From academic research, we know in a saturated media environment where people self-select into their preferred news channels, extreme media have polarizing effects on opinions. Also, this environment may produce ‘anchoring’ where people hold tightly to their previously held positions unwilling to consider alternative positions. Some research finds that these media can actually delegitimize political decisions such as election outcomes among those who are the most ardent believers in the messenger’s message. These are serious, serious issues.

What is missing, however, is a look at more direct—but equally important—aspects of these media like their capacity to increase political knowledge. To fill in this gap, I used two experiments and Annenberg survey data to see if extreme media usage and consumption could cause (experimentally) and correlate (survey) with political knowledge. My first set of subjects is made of university students, and the second set of subjects comes from workers on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk).

My experiments used three treatment videos using content from Glenn Beck on Fox News, Countdown with Keith Olbermann on MSNBC, and NewsHour with Jim Lehrer on PBS. Each of these videos was roughly the same length, and all discussed the content and events surrounding Arizona’s S.B. 1070 immigration law from 2010. To measure ‘knowledge,’ I asked subjects specific questions about S.B. 1070 making a score based on their answers.

Experiments are a valuable tool for research of this kind because you can expose people to real world content to see if the content has any effect. Because of randomization, we can attribute differences between the treatments and controls to the treatments specifically. We can also see if there are effects on other important questions such as if conservatives learn more from Beck or if liberals are more likely to learn from Olbermann.

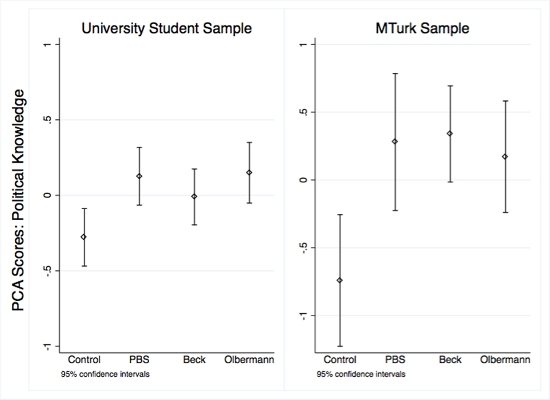

My main experimental findings are in the Figure 1. Generally, it’s clear that extreme media can inform subjects even on complex, emotionally charged issues like immigration. Extreme media are just as informative as traditional, nonpartisan news sources like PBS. These findings may seem intuitive, but it’s important to understand that there are several reasons why these media should not inform as they do here.

Figure 1 – Treatment Effects for Media on S.B. 1070 Knowledge

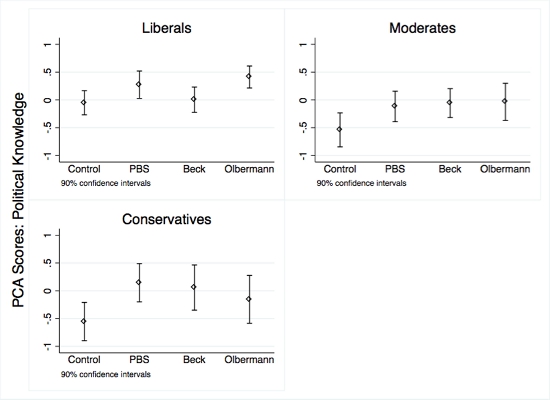

For instance, it may be the case that extreme media cause different effects for different groups of people. What happens when conservatives watch Beck or liberals watch Olbermann? In the next set of graphs, I break down the knowledge scores by ideology for each treatment condition.

Overall, the implications from Figure 2 suggest there are modest polarization effects with extreme media, which follows from previous work on attitudes. However, the modesty of the results is important because we might expect to see much more significant effects. It is difficult for people to overcome their prior attitudes, so finding that effects are not as large as one might assume is more evidence that partisan media are not as pernicious as some make them out to be.

Figure 2 – Student Sample Treatment Effects for Media on S.B. 1070 Knowledge, by Ideology

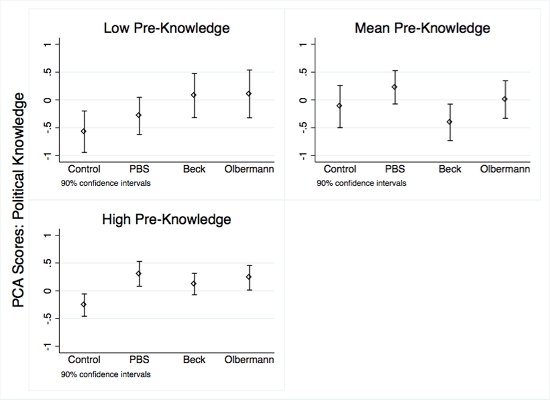

But ideology isn’t the only possible factor inhibiting extreme media viewers’ knowledge acquisition. Perhaps these effects are just another example of how ‘the rich get richer’ with political knowledge where those who know more already are able to get more out of the media they consume.

To see if this is a possibility, I asked subjects to answer some short political knowledge questions before they were given their treatment videos. I used these questions to classify subjects based on their prior political knowledge. Do people with more knowledge learn more than others from these media?

Shown in Figure 3, high political knowledge subjects are simply able to learn from media—which follows from previous research. Importantly, people with less political knowledge are able to learn slightly more from extreme media than from PBS. This is likely the case because extreme media present complex political information in a way that increasing their affective response and it’s entertaining. These results make extreme media similar to other types of media once thought to not contain political information like ‘soft news.’ Among subjects with the mean level of pre-knowledge, there is wide variability limiting any strong conclusions from these treatment effects. In general, it’s clear that only PBS was able to increase knowledge with these subjects, but neither Beck nor Olbermann were significantly different than the control.

Figure 3 – Student Sample Treatment Effects for Media on S.B. 1070 Knowledge, by Pre-Test Knowledge

It’s possible that the increases in political knowledge are artifacts of the lab. Given the spate of news stories that come out now and again about how various networks may or may not result in lower knowledge for their viewers, we need to know if extreme media are associated with political knowledge in the United States more generally.

Using the Annenberg data, I show that watching extreme media (coded using the hosts respondents reported watching) correlates with increases in general political knowledge even while controlling for a variety of important variables. I also break down extreme media into their liberal and conservative ideological directions and replicate the general finding: extreme media correlate with increased political knowledge.

What’s the take away? Using two sets of experiments and survey data, and using policy-specific knowledge and general political knowledge, I show that extreme media generate a positive externality for American politics: political knowledge. This is an important insight because many assume these media do not inform—or worse—actually misinform.

My research does not excuse the obviously bad behavior these hosts exhibit at times (i.e., Glenn Beck stating President Obama was racist or Olbermann’s ‘Worst Person in the World’ segments). What my research does do, however, is point out that there are redeeming qualities to these outlets and the hosts who develop a following based on their antics.

This article is based on the paper, ‘The Educative Effects of Extreme Television Media’, in American Politics Research.

Featured image credit: Gage Skidmore (Flickr, CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1PGmaBT

_________________________________

About the author

J. Benjamin Taylor – Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts

J. Benjamin Taylor – Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts

Benjamin Taylor is assistant professor of political science at Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in North Adams, Mass. He researches and teaches courses on political communication, media and politics, and American political behavior. He has recently published in American Politics Research, Politics and Religion, and Presidential Studies Quarterly, and is currently working on a book manuscript on extreme media.