In Congress, the representation of women currently stands at around 20 percent – far lower than it should be. But how can we encourage more women to run for office? Past research shows that in the 1980s and early 90s, women running for national office inspired other women to get involved in politics, but this did not occur in 2008, despite Hillary Clinton and Sarah Palin’s presidential and vice-presidential runs. In new research which measures young women’s interest in political involvement, A. Lanethea Mathews-Schultz, Bryan W. Marshall, and Mack D. Mariani find that the extent to which young women see themselves as likely to participate in politics is now much more tied to partisanship and ideology.

In Congress, the representation of women currently stands at around 20 percent – far lower than it should be. But how can we encourage more women to run for office? Past research shows that in the 1980s and early 90s, women running for national office inspired other women to get involved in politics, but this did not occur in 2008, despite Hillary Clinton and Sarah Palin’s presidential and vice-presidential runs. In new research which measures young women’s interest in political involvement, A. Lanethea Mathews-Schultz, Bryan W. Marshall, and Mack D. Mariani find that the extent to which young women see themselves as likely to participate in politics is now much more tied to partisanship and ideology.

Never before in the history of American electoral politics have women been so well positioned to secure both the Republican and Democratic nominations for president. For scholars working on issues related to gender and women’s representation, Hillary Clinton’s second bid for the presidency and Carly Fiorina’s increasingly competitive presidential campaign represent an opportunity to assess whether high-profile female candidates can change people’s thinking about women’s role in the American political system.

Though polling shows that 95 percent of Americans would vote for a “well-qualified person who happened to be a woman,” the vast majority of elected officeholders in the U.S. are men. According to the Center for the American Woman in Politics, women hold just 19 percent of seats in the US House of Representatives and 20 percent of seats in the US Senate. Things are not considerably better at the state level, where women hold 24 percent of state legislative seats and just 6 of 50 governorships.

The lack of female officeholders is explained, in part, by the lack of women candidates running for election in the first place. Studies show that when women run, they win as often as men do; but few women run. A large-scale study of college-age students conducted by Jennifer Lawless and Richard Fox found young women have lower levels of political ambition than young men. Their research suggests socialization plays a significant role in gender disparities in ambition, as women are less likely than men to be encouraged to run for office and less likely to be socialized by their parents to view political office as a career.

Another element of socialization that contributes to women’s underrepresentation is the lack of female role models, particularly in high-profile offices. Having few women in political office sends the message that politics is a career path best suited for men. Conversely, research suggests that when women run for or serve in high-profile political offices, they generate a “role-model effect” that inspires other women – particularly young women – to get involved in politics.

In one influential study, David E. Campbell and Christina Wolbrecht found strong evidence that the Geraldine Ferraro run for the vice-presidency in 1984 and the Year of the Woman elections of 1992 each had a strong role model effect on young women. In those years, which featured women candidates with a high, national-level profile, young women were significantly more likely than young men to see themselves becoming politically involved. In contrast, in the years without national female role models, young women were less likely than young men to see themselves becoming politically involved.

Finding evidence of a role model effect has proven more difficult in recent years. In new research, we find that young women no longer react the same way to the emergence of high profile female role models at the national level (our study can be accessed here for free until November 30). In contrast to previous role model events, Nancy Pelosi’s 2007 election as Speaker, Hillary Clinton’s first campaign for president in 2007-08, and Sarah Palin’s 2008 vice-presidential run were not associated with statistically higher levels of political involvement for young women.

Why didn’t Hilary Clinton, Nancy Pelosi, and Sarah Palin inspire young women in the same way that Geraldine Ferraro and the Year of the Woman did? Our analysis suggests that the American political system has become considerably more polarized and, as a result, the role model effects that do occur among young women are now strongly mediated by partisanship and ideology.

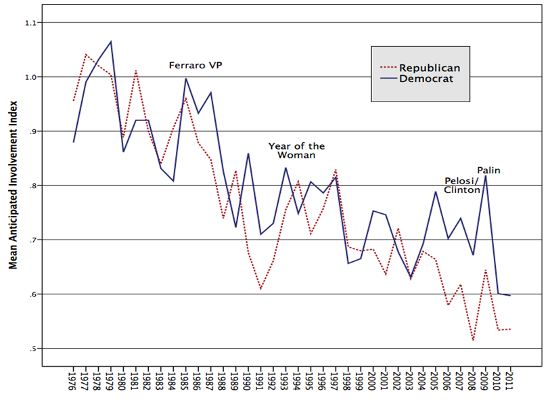

Figure 1 below, which is based on survey data from the Monitoring the Future Study of 12th grade students, tracks the level of anticipated political involvement of young Republican and Democratic women between 1976 and 2011. Though there is a general trend downward over time, both Republican and Democratic women expressed increased interest in political involvement following the Ferraro vice-presidential run and the Year of the Woman elections. There is a clear divergence, however, between Republican and Democratic young women during the Pelosi & Clinton role model events. In 2006-2008, Democratic women expressed sharply higher levels of anticipated involvement and Republican women did not. Though both groups of women moved upward in the year following Palin’s vice-presidential run, similar jumps among men during this period make it unclear whether this was a gender-related shift.

Figure 1 – Anticipated Political Involvement of Republican and Democratic Young Women, 1976-2011.

Source: Monitoring the Future Survey Research Center, Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR). Analysis by authors.

A similar pattern is evident when comparing liberal and conservative young women over the same time period. Both liberal and conservative women expressed higher levels of anticipated political involvement in the years following the Ferraro vice-presidential run and the Year of the Woman elections, but only liberals show higher levels of involvement in 2007-2008. Likewise, a shift among conservative women following Palin’s run is evident, but the extent the shift was the result of a role-model effect is somewhat muddled by a similar shift among conservative men.

Our research suggests that the extent that young women see themselves as likely to participate in politics in the future was tied much more closely to partisanship and ideology during the late 2000s than it was in previous years. Nonetheless, how this plays out in the coming presidential election remains uncertain. Although the political environment seems more polarized than ever, the emergence of viable female presidential candidates in both major parties at the same time is uncharted territory.

The degree to which candidate gender is emphasized, and the importance of gender issues in the campaign will also shape how women react to the Clinton and Fiorina candidacies. To some extent, the Clinton and Fiorina campaigns themselves convey the complexity of the interplay between gender, party, and ideology and the potential effects of this interplay for voters. Clinton has embraced women’s issues as central to her campaign (going as far as to appropriate the phrase “using the gender card” during a campaign Facebook chat). Paradoxically, more recent polls suggest that Clinton has lost some support among Democratic women. Fiorina, in contrast, has been portrayed as a candidate who can combat the perception of a “Republican War on Women”; she claims that “all issues are women’s issues” and is polling strong among Republican women. In the second debate, Fiorina made her opposition to Planned Parenthood funding a centerpiece in the campaign and subsequent controversy and media coverage of her remarks have further highlighted her stance on the abortion issue. Clearly, the ways in which female role models like Clinton and Fiorina portray themselves matters. So do the issues they focus on and campaign rhetoric that they employ.

Will Hillary Clinton and Carly Fiorina inspire young women to political engagement? We believe that the answer to this question is yes, but the young women the candidates inspire will not be the same. Given the highly polarized nature of national elections and campaigns, we don’t expect either presidential hopeful to produce a pure role model effect like the Ferraro vice-presidential candidacy. Rather, we expect party and ideology to play key roles in any role model effects that occur in the 2016 contest.

On the national electoral stage, the evidence points to increased women’s political involvement within the confines of shared party and ideology with women candidates. Both Hillary Clinton and Carly Fiorina’s candidacies convey the important symbolic message that politics is, and ought to be, open to women. How young women and young men respond, however, will hinge in part on the partisan and ideological prisms through which the voters view themselves and how the candidates frame their respective campaigns.

This article is based on the paper ‘See Hillary Clinton, Nancy Pelosi, and Sarah Palin Run? Party, Ideology, and the Influence of Female Role Models on Young Women’ in Political Research Quarterly.

Featured image: Hillary Clinton credit: Hillary for America (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0), (r) Carly Fiorina credit: Gage Skidmore (Flickr, CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1MbV9GJ

_________________________________

A. Lanethea Mathews-Schultz – Muhlenberg College

A. Lanethea Mathews-Schultz – Muhlenberg College

A. Lanethea Mathews-Schultz is Associate Professor of Political Science at Muhlenberg College. Her research and teaching interests include gender and American political development, political behavior, and American political institutions. She is particularly interested in understanding how, when, and with what consequences relationships between citizens and political institutions change over time. Matthews-Schultz’s research has appeared in Political Research Quarterly, the Journal of Political Science Education, Politics and Gender, the Journal of Women, Politics, and Policy, and PS: Political Science and Politics.

Bryan W. Marshall – Miami University

Bryan W. Marshall – Miami University

Bryan W. Marshall is professor and Assistant Chair of the Department of Political Science at Miami University. His teaching and research focuses in the areas of Congress, congressional-executive relations, and quantitative methods. Marshall’s recent articles appear in Social Science Quarterly, Legislative Studies Quarterly, Presidential Studies Quarterly, Journal of Theoretical Politics, American Politics Research, and Conflict Management and Peace Science.

Mack D. Mariani – Xavier University

Mack D. Mariani – Xavier University

Mack D. Mariani is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. Mariani earned his BA at Canisius College and his MA and PHD at the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University. Mariani’s recent research has appeared in Political Research Quarterly, Legislative Studies Quarterly, Political Science Quarterly, PS: Political Science and Politics, Politics and Gender, the Journal of Women, Politics, and Policy, and the Journal of Political Science Education.