In the 2016 presidential primaries, both female candidates, Hillary Clinton and Carly Fiorina, have made extensive use of Twitter to reach out to female voters. In new research, using data gathered during the 2012 election, Heather Evans and Jennifer Hayes Clark look at how female candidates make use of Twitter. They find that women are much more likely to ‘go negative’ on Twitter, and to use Twitter to discuss policy issues, especially those that affect women the most.

In the 2016 presidential primaries, both female candidates, Hillary Clinton and Carly Fiorina, have made extensive use of Twitter to reach out to female voters. In new research, using data gathered during the 2012 election, Heather Evans and Jennifer Hayes Clark look at how female candidates make use of Twitter. They find that women are much more likely to ‘go negative’ on Twitter, and to use Twitter to discuss policy issues, especially those that affect women the most.

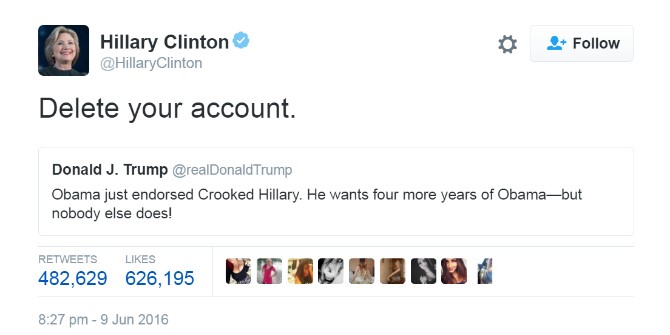

With the 2016 presidential campaign looming on the horizon and two female candidates eyeing their White House prospects, it is important for us to reflect on research about how gender affects the campaigning style of candidates for political offices. Those who follow former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s campaign on Twitter have surely noticed her concerted effort to reach out to female voters by adopting a gendered hashtag (#womenforhillary). Former Hewlett Packard CEO Carly Fiorina has also marketed herself to potential female voters. For instance, when Donald Trump made a comment about her appearance (“look at that face”), she politely replied “I think women all over this country heard very clearly what Mr. Trump said.” She then took his comment and made what some are calling the best ad so far in the presidential election, titled “Faces” where she shows the faces of women in America, young and old, and makes a call for women to engage in the election.

Do women traditionally market themselves to other female voters? Our recent research shows that gender affects the likelihood of candidates will “go negative” and the likelihood of discussing so-called “women’s issues” on Twitter. Using a dataset gathered during the 2012 election, we show that women are significantly more likely to discuss policy issues, especially those that disproportionately affect women as a group.

We coded each tweet sent by candidates for the 2012 House for whether or not it pertained to a policy issue as opposed to constituency outreach, mobilization, personal messages, or something else. Issue-specific tweets ranged considerably in the types of issues discussed, including health care (e.g., the Affordable Care Act, “Obamacare”), education, foreign policy, and many other important national issues. We then examined “female issue” tweets, drawing on previous academic literature. We focused on both the traditional issues associated with women as a group (health, welfare, education, and the environment) as well as feminist concerns seeking to improve the social, economic, and political status of women as a group (equality/equal rights, Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, Questioning, and Allied (GLBTQA) rights, poverty). We also included crimes that disproportionately affect women, such as rape and domestic violence. In addition, we classified Plan B, abortion, pro-choice, and pro-life as “women’s issues.” We also coded the tone of each tweet (positive, negative).

Credit: Andy Melton (Flickr, CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Our research shows that first, unlike previous research on gender and campaigning, women are significantly more likely to go negative. Female candidates are also more likely to discuss issues in general, especially “female issues.” We also find that the context of the race influences what female candidates talk about. When additional women are added to the race, the number of negative tweets and the number of issue tweets increase. At the same time, however, adding more women to a race decreases the number of tweets sent about “female issues.”

These results demonstrate that women seeking seats in the US House act differently than their male counterparts on Twitter. Women are using Twitter like the “out-party” typically uses new social media. They also discuss women’s issues when they are running as the only woman in the race. When additional women are added to the contest, women are less likely to talk about these issues possibly because they are not as distinguishable from their female competitors.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that women seeking the presidency tweet in this fashion. Future research should establish whether this is the case, especially since we may see female nominees for the presidency in 2016. If both Hillary Clinton and Carly Fiorina become their party’s nominees, we may see fewer mentions of “women’s issues” by each on Twitter.

This article is based on the paper ‘“You Tweet Like a Girl!” How Female Candidates Campaign on Twitter’ in American Politics Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1IgMMCT

_________________________________

Heather Evans – Sam Houston State University

Heather Evans – Sam Houston State University

Heather Evans is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at Sam Houston State University. Her primary research interests are political participation and behavior, public opinion, competitive elections, media and politics, the status of women in the political science discipline, and political psychology.

Jennifer Hayes Clark – University of Houston

Jennifer Hayes Clark – University of Houston

Jennifer Hayes Clark is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science and a Research Associate at the Center for Public Policy at the University of Houston. Her primary areas of research interest include American political institutions, public policy, and quantitative research methodology.