The recreational use of marijuana in Colorado has now been legal for more than three years, but cities, municipalities and counties have had the freedom to choose whether or not to legalize the drug or for it to remain banned. In new research using survey data and panel interviews with Coloradan local administrators, Tracy L. Johns finds that in their decision making these officials had to consider often divided local public opinion against the potential economic costs and benefits of legalization and the workload of enforcing marijuana policies.

The recreational use of marijuana in Colorado has now been legal for more than three years, but cities, municipalities and counties have had the freedom to choose whether or not to legalize the drug or for it to remain banned. In new research using survey data and panel interviews with Coloradan local administrators, Tracy L. Johns finds that in their decision making these officials had to consider often divided local public opinion against the potential economic costs and benefits of legalization and the workload of enforcing marijuana policies.

Broadly, public opinion on the legalization of marijuana has shifted considerably over the past decade. In 2006, about one in three people in the US supported marijuana legalization. By 2015, more than half thought the use of marijuana should be made legal, with more than two in three of those age 18 to 34 favoring legalization.

Although marijuana continues to be an illegal substance under federal law, in line with the growing shift in public opinion, many states and local governments have decriminalized marijuana in various ways, including legalized sales and distribution for recreational use in Alaska, Colorado, Oregon, and Washington. As a local control state, Colorado cities, municipalities, and counties may choose whether or not to adopt marijuana legalization policies in their jurisdictions and how to do so, making the policy a compelling study in the policy adoption and implementation process.

In new research based on surveys of 110 Colorado local administrators and interviews with a panel of Colorado local officials regarding marijuana legalization policies in their jurisdictions, I found that their decisions were related to public opinion, economics, and existing medical marijuana policies. These dynamics affected both the decision to permit and the decision to prohibit recreational marijuana. In early planning and implementation, cities used existing medical marijuana policies to shape recreational marijuana policies.

Culture & Public Opinion

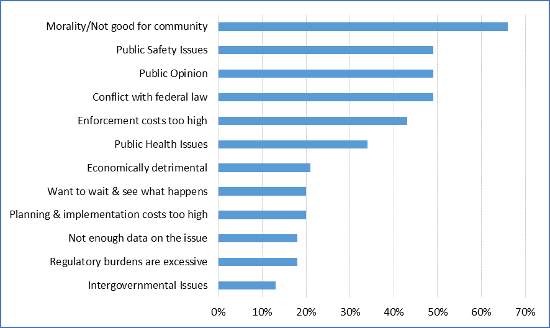

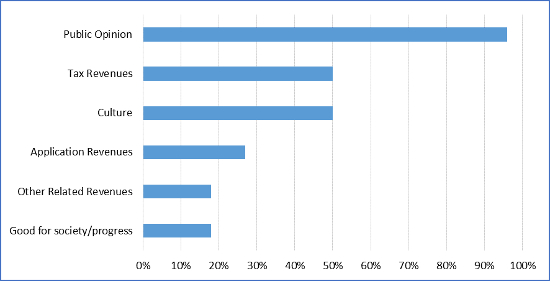

Consistent with state licensing records, substantially more cities surveyed for this research decided to either ban (56 percent) or place a moratorium (25 percent) on recreational marijuana establishments than decided to permit them (20 percent). Community culture and public opinion played a significant part in administrators’ decisions. As Figure 1 shows, about two-thirds of respondents from prohibiting cities cited “morality/not good for community” as a reason for banning recreational marijuana sales and about half said that “public opinion” was a reason recreational marijuana was banned in their jurisdictions. Nearly all of the respondents from cities permitting recreational marijuana said that “public opinion” was a reason for doing so, and half of these cities said “culture” was a reason for doing so (Figure 2).

Figure 1 – Reasons for banning marijuana

Figure 2 – Reasons for permitting marijuana legalization

The panel discussion revealed similar findings. One panelist said succinctly, “My board’s answer was that the people of Colorado voted to allow marijuana and the town was upholding the voice of the people.” Much of the discussion, however, highlighted the complexities of dealing with diverse publics. Many administrators noted that citizen votes to allow marijuana businesses in their communities were very close, showing a “split community” opinion. So, while council members felt passage of marijuana-related bills indicated general public support, they were also mindful of the percentage of voters who were not in support when considering regulations and council decisions.

The economics of marijuana legalization

Colorado’s Amendment 64 ballot initiative to legalize recreational marijuana (and Proposition AA in 2013 to tax recreational marijuana) earmarked the first $40 million of state excise tax revenue for public school construction, with other marijuana tax revenues reserved to fund public education campaigns, health-related services, and public safety initiatives. Amendment 64 also allocates 15 percent of the sales tax collected by the state on marijuana back to cities and counties where retail sales occur. When any locally levied taxes are included, jurisdictions allowing marijuana sales could recognize distinct economic benefits.

My survey showed that economic factors contributed to community choices both for and against policy adoption. About two-fifths of respondents from cities that banned recreational marijuana sales noted “enforcement costs are too high” as a reason for prohibition, and one-fifth expressed a view that “planning and implementation costs are too high.” Respondents from cities permitting recreational marijuana noted revenues generated by taxes, applications for establishments, and by other related businesses (like tourism) as reasons for permitting recreational marijuana.

Most of the panelists stated that economic considerations were not primary factors in their city’s decision on recreational marijuana. One panelist, however, was clear that there “was an economic factor” to approval in her community as the city owns their utility company and marijuana grows require large quantities of electricity (e.g. constant lighting, temperature control, etc.). She also noted that marijuana enterprises have brought “the first new commercial light-industrial construction that this town has seen in the past 20 years” and “new manufacturing operations in a community that could really use the jobs.”

In an interesting overlap of cultural and economic factors, several panelists whose cities initially prioritized culture over economic aspects of the policy said that the resulting financial benefits (coupled with few problems) have changed the perceptions of some former opponents.

Implementing Recreational Marijuana Policies

The survey data showed a strong, significant relationship between currently permitting medical marijuana and the decision to permit recreational marijuana. More than four-fifths of cities that currently permit medical marijuana also permitted recreational marijuana sales and all of the cities that banned medical marijuana either banned or placed a moratorium on recreational marijuana sales.

Adapting a phrase often used to describe the relationship between marijuana use and further drug use, panelists described medical marijuana as “a gateway policy” to recreational marijuana. One panelist noted that medical marijuana “helped pave the way” in terms of “development and implementation and tolerance and community perception” of recreational marijuana. Most of the panelists’ cities transitioned existing policies and regulations already in place for medical marijuana to recreational marijuana and found that this was a “smooth transition” for their communities.

Panelists emphasized the on-going nature of the planning and implementation process – noting the substantial amount of council time occupied by issues related to marijuana despite it being a relatively small portion of city revenue and operating functions. All agreed that recreational marijuana is a “policy experiment” that, by its nature, carries a learning curve necessitating continual adaptation.

In practice, three prominent issues related to enforcing recreational marijuana policies were evident in the panel discussion: the amount of time required to process applications, renewals, licenses, and inspections; issues caused by lack of support by the surrounding county; and, issues caused by lack of support from the state. Several panelists called attention to the heavy workload marijuana policies created for various government offices, most notably the clerk’s office (or other licensing departments) and law enforcement.

Several of the panelists represent cities in which recreational marijuana has been approved in their cities, but not in their counties, leading to problems: “We do not have the support of law enforcement here as we contract with the County for police protection and the County has banned marijuana.” Similarly, “…the Health Department doesn’t want to get involved because they consider it [marijuana infused products] a drug not a food.”

While about three in five surveyed cities said that state-level departments had been or would be involved in the enforcement of recreational marijuana regulations with their local governments, panelists expressed disappointment with lack of involvement by the State. Panel members singled out neglected facility testing requirements as problematic.

Lessons learned from these local administrators in Colorado should prove useful as more states and local governments consider permitting and enacting sales of recreational marijuana.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Managing a Policy Experiment: Adopting and Implementing Recreational Marijuana Policies in Colorado’, in State and Local Government Review.

Featured image credit: tales of a wandering youkai (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1MTMKSi

_________________________________

Tracy L. Johns – University of Florida

Tracy L. Johns – University of Florida

Tracy L. Johns is the Research Director at the Florida Survey Research Center (FSRC) at the University of Florida and holds a special faculty appointment as an Assistant In with the UF Department of Political Science. She has designed and overseen the implementation of hundreds of research projects at the FSRC and also teaches graduate courses in data analysis and research methodology. Her primary research interests are focused on the study of crime and deviant behavior and issues of inequality.

The recreational use of marijuana in Colorado has now been legal for over 3 years now. Consumption was legalized on December 10, 2012 when Governor John Hickenlooper ratified the ballots and added the law to his state’s constitution. Marijuana sales were legalized later.

Thanks for this John – the post has now been updated to reflect your comment.

– USAPP Editor