How do voters react to politicians who switch parties? Using the 2014 gubernatorial election in the swing state of Florida as a case study M. V. (Trey) Hood III and Seth C. McKee find that despite his positioning of himself as a moderate, when the state’s former Republican Governor Charlie Crist chose to run as a Democrat, most voters saw the switch as politically opportunistic rather than principled. This view then translated into a much lower likelihood that people would vote for the former Republican.

How do voters react to politicians who switch parties? Using the 2014 gubernatorial election in the swing state of Florida as a case study M. V. (Trey) Hood III and Seth C. McKee find that despite his positioning of himself as a moderate, when the state’s former Republican Governor Charlie Crist chose to run as a Democrat, most voters saw the switch as politically opportunistic rather than principled. This view then translated into a much lower likelihood that people would vote for the former Republican.

Switching parties in the lead up to a vote can be electorally fatal, something that former Florida Governor Charlie Crist discovered in 2014 when he ran for his old job against now Republican Governor Rick Scott. While Florida is typically grouped as a ‘Southern’ state, many would question this given that one has to go back to the 1940 US Census to find a time when a majority of residents were actually born there (with most non-natives hailing from outside of Dixie, or Latin America).

Not only is Florida unique for its remarkably diverse electorate; sometimes referred to as a microcosm of the nation because of its demographics, it has also been a perennial presidential battleground since President George H. W. Bush narrowly carried the state while losing his bid for reelection to Democrat Bill Clinton in 1992. One of the reasons for Florida’s status as a swing state is that Democrats and Republicans tend to offset each other while a large share of independent voters typically determine the victor. In state legislative and congressional politics the GOP is dominant, but in high-profile statewide elections (e.g., US Senate and Governor) and particularly for president, victory margins often rest on a razor. In the debacle of 2000, Republican George W. Bush bested his Democratic opponent Al Gore by a mere 537 votes! In 2012, President Obama defeated Republican Mitt Romney by less than 1 percentage point.

Florida’s electoral politics are an important influence on our recent research, where we investigated an intriguing matchup in the Sunshine State: the 2014 gubernatorial contest pitting the incumbent Republican Rick Scott against Democrat Charlie Crist. There are several storylines that made this race worthy of examination. First, Charlie Crist was Rick Scott’s Republican predecessor in the governor’s mansion – serving from 2006 to 2010. Second, Crist passed up certain reelection in 2010 for a shot at an open US Senate seat but when it was evident that former state house speaker Marco Rubio would prevail in the GOP primary, Crist switched to “no party affiliation” and still ended up losing to Rubio in the general election. Meanwhile, the multimillionaire and unabashed political amateur Rick Scott bucked the GOP establishment, dropped about $70 million of his own fortune on the race, avoided all media encounters (save for the debates), and in the 2010 Republican tsunami barely won the open gubernatorial seat.

From the moment he assumed office, Governor Scott has had an approval rating more unfavorable than favorable primarily because he has governed from the right end of the political spectrum, rankling median Florida voters. By comparison, in his tenure as a public official, Charlie Crist always tried to position himself in line with the popular middle of the Florida electorate. Perhaps sensing a gradual shift among the electorate in the Democratic direction, and knowing firsthand that running as an independent in a two-party system usually ends in resounding defeat, about a month after the 2012 presidential election, Crist announced that he was switching to the Democratic Party. As any casual observer of Florida politics could surmise, it appeared that Crist was readying himself for a run at his old post, especially since Governor Scott was highly unpopular but intended to seek reelection. Thus, the 2014 race posed the Florida voter with an interesting dilemma: behind door number 1 was the unpopular governor and door number 2 contained the opportunistic challenger. Given these undesirable options, who would prevail?

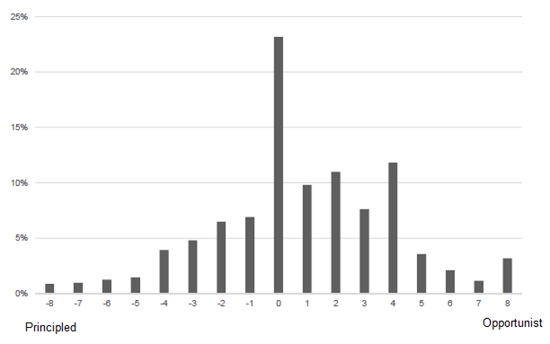

Relying on an index that we adopted from a previous study on party switching, we devised a principled-opportunism (P-O) scale to determine how Crist’s party switch affected voter preferences in the 2014 gubernatorial election. Based on a summation of scored responses involving four questions regarding Crist, the P-O scale ranges from a low of -8 to a high of +8, with the low end designating the opinion that Crist’s party switch was done purely out of principle whereas the high end indicating the switch was a purely opportunistic decision done to further political ambition. Figure 1 presents the distribution of the P-O scale for our survey of registered Florida voters in the 2014 election. From the figure it is evident that a large number of respondents viewed Crist as more of an opportunist than a politician nobly realigning himself with the party advancing his core principles.

Figure 1 – Principled-Opportunism Scale Distribution

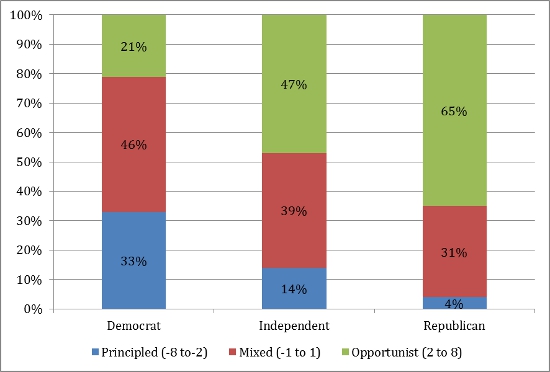

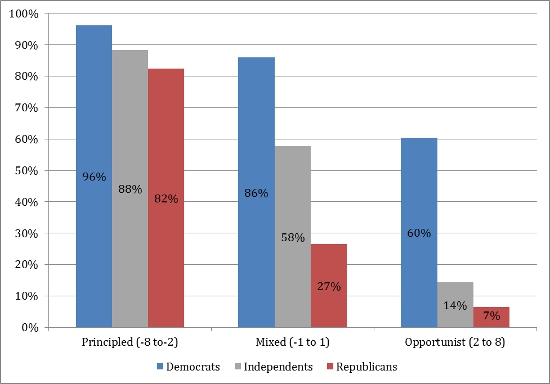

In Figure 2, we go a step further by displaying a bar graph of where respondents placed Crist on the P-O scale (-8 to -2 = principled, -1 to 1 = mixed, and 2 to 8 = opportunist) based on their party affiliation. Not surprisingly, almost 2 out of 3 Republicans (65 percent) placed Crist’s switch in the opportunist range, whereas a clear plurality of independents (47 percent) did the same. Most Democrats (46 percent) viewed the switch as a mixture of principled and opportunistic behavior, but even so, more than 1 out of 5 (21 percent) thought Crist converted mainly out of political calculation. We follow up in Figure 3 with a bar graph of vote choice according to party affiliation and the placement of Crist on the P-O scale. Among Democrats, support for Crist declines from over 96 percent in the principled category to 60 percent for those who viewed Crist’s switch as opportunistic. Within the small portion of Republicans who thought the switch was a principled maneuver (4 percent, see Figure 2), 82 percent backed Crist, whereas fewer than 7 percent of GOP identifiers supported Crist if they viewed his switch as opportunistic. Most independents stuck with Crist if they perceived his move to the Democratic Party as principled (88 percent) or mixed (58 percent), but their support drops off a cliff (to 14 percent) if he is viewed as opportunistic.

Figure 2- Crist Placement on P-O Scale by Party Affiliation

Note: Entries are weighted column percentages

Figure 3 – Vote for Crist by P-O Scale and Party Affiliation

Note: Entries respresent the weighted percentage in each category voting for Crist

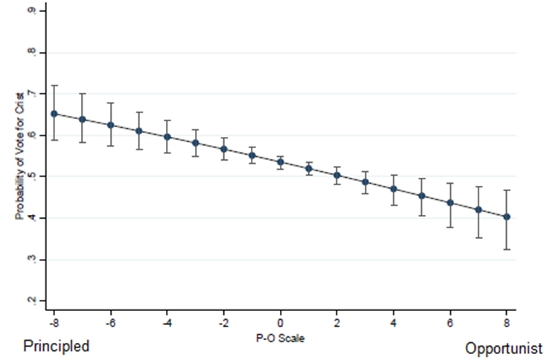

Finally, we performed a multivariate analysis of vote choice in the 2014 Florida gubernatorial election in order to gauge the influence of Crist’s party switch once we control for numerous confounding factors. We estimated vote choice, controlling for party identification, ideology, race/ethnicity, education, income, gender, age, interest in the campaign, and favorability toward Scott and Crist. The principled-opportunism scale was the variable of interest. Even after controlling for the aforementioned factors, the P-O scale registered a large effect on vote choice. The P-O scale variable was negative and statistically significant: respondents who viewed Crist’s switch as an act of political opportunism were much less likely to vote for him. Setting the other controls in the model at their observed values, Figure 4 plots the likelihood of voting for Crist from the most principled score (-8) to the most opportunistic (+8). Moving across the scale from most principled to most opportunistic, the probability of voting for Crist drops from .65 to .40.

Figure 4 – Vote for Crist by Principled-Opportunism Scale

When all the votes had been counted, Governor Scott narrowly beat back former Governor Crist’s challenge, with 50.6 percent to 49.4 percent of the two-party vote. It was another nail-biter in the state of Florida. As scholars who study party switching know, the decision to convert is generally an electorally costly action, though it typically doesn’t end in defeat. In 2014 the Florida voter truly had to make a choice between the lesser of two evils, and it seems incontrovertible that Crist’s party switch was an instance in which such an action proved the electoral kiss of death.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Sunshine State dilemma: Voting for the 2014 governor of Florida’ in Electoral Studies.

Featured image: Former Florida Governor, Charlie Crist, Credit: Andres LaBrada Photographer (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1PdHYkP

_________________________________

M.V. (Trey) Hood III – University of Georgia

M.V. (Trey) Hood III – University of Georgia

M.V. Hood III is a professor of political science at the University of Georgia where he conducts research in American politics and policy.

Seth C. McKee – Texas Tech University

Seth C. McKee – Texas Tech University

Seth C. McKee is an associate professor of political science at Texas Tech University. His primary area of research focuses on American electoral politics and especially party system change in the American South. He has published research on such topics as political participation, vote choice, redistricting, party switching, and strategic voting behavior. McKee is the author of Republican Ascendancy in Southern US House Elections (Westview Press 2010), and more recently the editor of Jigsaw Puzzle Politics in the Sunshine State (University Press of Florida 2015).