Proactive firms help create social policies that would otherwise lack support, write Younsung Kim and Nicole Darnall.

Proactive firms help create social policies that would otherwise lack support, write Younsung Kim and Nicole Darnall.

Many proposed policies that could improve social welfare never see the light of day because of intractable debates among critical stakeholders and particularly business opposition. We suggest that collaborative governance approaches involving government and business stakeholders may successfully formulate policies that address complex social issues, and that otherwise lack policy support.

Many businesses are promoting social welfare by voluntarily eradicating poverty, eliminating discrimination, or protecting the environment, while enhancing their bottom line, and some of them actively support the mandatory regulation that further improve these societal conditions. For instance, in December 2014, more than 200 firms (including Nike, Starbucks, Mars Inc., and Kellogg) publicly supported the US Environmental Protection Agency’s proposed carbon regulations in an open letter acknowledging that “addressing climate change is one of America’s greatest economic opportunities of the 21st century.” These businesses “applaud the EPA for taking steps to help the country seize that opportunity.”

However, policy makers are often reluctant to engage business stakeholders in policy formulation because of concerns about agency capture and equity, since businesses typically oppose mandatory regulation and are motivated by their self-interest.

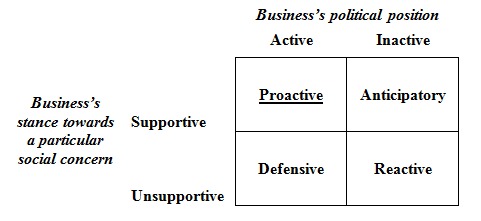

In a recent study, we suggest that businesses’ responses to proposed mandatory regulations are not one-dimensional. We suggest that when confronted with the prospect of mandatory regulation, firms assess the political and social setting, and frame the possible regulation as either a threat or an opportunity – creating four types of sociopolitical responses.

Four Types of Sociopolitical Business Responses to Mandatory Regulation

Related to the political setting, during policy formation, firms strategically engage for the purpose of maintaining existing business values or creating new ones. Those that seek to maintain existing business conditions typically regard pending regulation as a threat that destabilises their market competitiveness and actively lobby against mandatory policy. By contrast, other firms regard a potential policy or regulation as an opportunity, and actively endorse mandatory regulation to increase their market position. While their responses differ, both types of firms are politically active. However, other firms may be politically inactive and disengage from the political discussion, recognising that costs of engagement are too high and policy formation is inevitable.

With respect to the social setting, when a firm’s strategic priorities are congruent with societal concerns, it is more likely to coordinate with government actors to address those concerns. Conversely, if a firm’s organisational priorities are incongruent with a social issue, it will see little benefit associated with advancing mandatory policy to address that issue, and is more likely to oppose policy proposals and partner with other individuals and organisations who also oppose them.

Firms’ responses to the sociopolitical environment are thus either defensive, reactive, proactive, or anticipatory.

Figure 1 – Types of sociopolitical business responses towards mandatory regulation

Applied to firms’ responses to mandatory climate change regulation, for instance, defensive firms focus on protecting the status quo and question scientific evidence about the existence of the social problem and thus the societal benefit of climate regulation. Reactive firms are socially unsupportive toward regulating businesses’ climate pollutants, and remain politically inactive in the policy debate. Anticipatory firms accept climate change as a social issue and actively mitigate their own climate change impacts, however, they are inactive in political discussions about forming mandatory climate regulations. Proactive firms endorse the scientific evidence of climate change, respond to reduce climate pollutants, and are politically active at endorsing mandatory climate regulation.

Ideal Collaborators

Ideal collaborators are firms that:

- Recognise that a social problem exists and that their ability to address it is interdependent with the actions taken by others;

- Pursue private economic benefits that are aligned with broader social benefits, because they can gain access to markets that otherwise did not exist or because they can better address changing expectations from consumers, investors, and regulators;

- Are willing to commit to business-governmental partnership agreements and engage in joint problem solving with different social actors.

We suggest that proactive firms are ideal collaborators with government actors who wish to advance mandatory policy that address complex social problems.

So, our message is clear: proposed policies that could improve social welfare – but that become embedded in messy policy debates with significant business opposition – would benefit by collaborative business-government partnerships with proactive firms. These partnerships can help identify creative policy solutions, enhance the legitimacy of mandatory regulations, and improve the likelihood of successful policy formulation and implementation.

Featured image credit: Mexico City Business Centre, by Munir Hamdan, CC-BY-2.0

This post is based on the authors’ paper Business as a Collaborative Partner: Understanding Firms’ Socio-Political Support for Policy Formation, (August 4, 2015), Public Administration Review, 2015 .

This article was originally posted on LSE Business Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1Q2blfN

_________________________________

Younsung Kim – George Mason University

Younsung Kim – George Mason University

Younsung Kim is an Assistant Professor of Environmental Science and Policy at George Mason University. Dr. Kim’s research focuses on collaborative governance approaches and businesses’ self-regulatory actions to global sustainability challenges that are derived from her professional experience at the Ministry of Environment in South Korea and the World Bank. Email: ykih@gmu.edu.

Nicole Darnall – Arizona State University

Nicole Darnall – Arizona State University

Nicole Darnall is Professor at Arizona State University, and Associate Director of the Center for Organization Research & Design. She is a leading scholar in nonregulatory governance and sustainable enterprise, operating at this nexus of management and public policy. Email: ndarnall@asu.edu