Republicans have had a better reputation on issues of security and foreign policy with voters compared to the Democrats. In new research, Mirya R. Holman, Jennifer L. Merolla, and Elizabeth J. Zechmeister find that this reputation has a gender dimension as well. Using a national online sample, they find that in times of apparent safety voters who hold these perceptions think more poorly of both Democratic men and women leaders, but when they are concerned about a terrorist attack, such attitudes only harm women Democratic leaders.

Republicans have had a better reputation on issues of security and foreign policy with voters compared to the Democrats. In new research, Mirya R. Holman, Jennifer L. Merolla, and Elizabeth J. Zechmeister find that this reputation has a gender dimension as well. Using a national online sample, they find that in times of apparent safety voters who hold these perceptions think more poorly of both Democratic men and women leaders, but when they are concerned about a terrorist attack, such attitudes only harm women Democratic leaders.

Terrorism casts its shadow over individuals and communities, shaping politics and voter decision making. When the threat of a violent attack by terrorists looms large, gender stereotypes lead to increased public support for male political candidates. Our research demonstrates that this bias harms female candidates who lack characteristics that counter an association between femininity and perceived weakness on national security. Party affiliation is one such counter-weight: affiliation with political parties that have stronger reputations on security (in the US, the Republican Party) immunizes some women against the negative effects of gender stereotypes, while leaving those associated with other parties (the Democratic Party) vulnerable.

Nearly one in three Americans agree that “men make better political leaders than women,” according to a survey by the Latin American Public Opinion Project. Preferences for male leadership are even higher when the US public is asked what type of leader is most capable of handling terrorism. In this case, more than three in four respondents to an Angus Reid poll selected either a Republican male (43 percent) or a Democratic male (33 percent), with the remaining individuals split between a Republican female (18 percent) or a Democratic female (6 percent). These values also illuminate the relevance of partisanship: Republican candidates generally are seen as better leaders than Democratic candidates in times of terror threat.

The tendency to view female Democrats as weak on terrorism is even stronger among individuals who are worried about terrorism, even when we control for other factors associated with political decision-making. Interestingly, though, elevated concerns about terrorism do not significantly change standing evaluations of Democratic males and actually boost status quo evaluations of Republican women. In short: When terrorist threats are on people’s minds, the leadership capacity of female Democratic leaders is treated with greater than usual skepticism.

What accounts for these dynamics? Our answer underscores the relevance and application of political gender stereotypes. Gender stereotypes lead people to believe that female politicians may be more compassionate and trustworthy, better able to handle children’s and women’s issues, and more liberal and Democratic. Male politicians, in contrast, are seen as more assertive, stronger leaders, better able to handle foreign affairs, and defense, and more conservative.

Interestingly, gender stereotypes are associated with political parties as well. In the US, scholars have shown that the Democratic Party is perceived as more feminine and less capable on national security, while the Republican Party is perceived as more masculine and more capable on national security issues.

The overlap between partisan and gender stereotypes is consequential for the type of politician that individuals turn to when terrorist threat increases. In an experiment conducted via a national online sample of US citizens, we demonstrate that gender stereotypes function in ways that place Democratic female candidates at a significant disadvantage when terrorism is salient. The experiment randomly assigned some individuals to read about a hypothetical election, taking place in either a time of terrorist threat or a time of relative well-being and pitted a Republican male or female against a Democratic male or female.

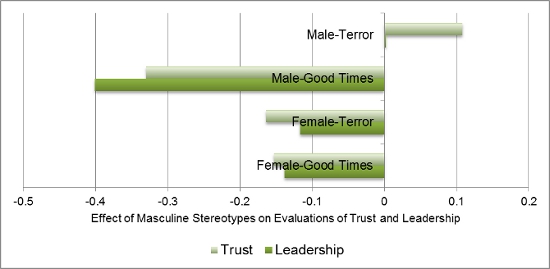

As Figure 1 shows, our analyses reveal that male gender stereotypes (measured via a set of questions asked within the survey) harm both male and female Democratic candidates in times of well-being. That is, individuals who think men are stronger leaders and more competent on national security, downgrade their evaluations of the trustworthiness and leadership capacity of both Democratic males and females. However, the negative effect of male stereotypes on the Democratic male candidate washes away among those who read about a condition of terrorist threat. We surmise that this condition made gender even more relevant and thus the Democratic male’s gender counter-acted the association between the Democratic Party label and perceived weakness on national security. The negative effects of male gender stereotypes persist, however, for the Democratic female in the terrorism condition, and this leaves her in the most disadvantaged position.

Figure 1 – Estimated Effect of Male Stereotypes on Trait Evaluations for the Democratic Candidate, by Gender of Candidate and Experimental Condition (Terror Threat vs. Good Times)

In short, when individuals are threatened by terrorism, candidate gender and partisanship combine to harm Democratic female candidates. Data from the experiment help to explain this disadvantage through a deactivating process. The Republican female candidate is – all else equal – immune to these negative effects, suggesting that Republican partisanship counters the stereotype.

Our findings have important implications for understanding the forces that may harm women’s electoral chances for executive office. These results suggest that, when terrorism is in the news, Democratic female candidates may have lower success in primaries and general elections. This is particularly important given that women are more likely to run under the Democratic ticket than the Republican ticket. At the same time, national security threat can give a comparative advantage to Republican women seeking executive office. The recent growth of Republican women contesting and winning gubernatorial office fits within this pattern.

An important question – especially given the current presidential campaign season in the United States – concerns the factors that counter the effect of male stereotypes on Democratic females. That Republican women are immunized against the effects of a terrorist threat due to their party’s reputation in that arena suggests experience in foreign policy, defense, and international affairs may advantage a Democratic female in times of national crisis. In previous research we found that Hillary Clinton was disadvantaged in a context marked by terrorist threat, yet that study was conducted prior to her position as Secretary of State. In Clinton’s bid for president in 2016, her experience in that position could serve to buttress her against gender and party stereotypes in a climate of national security threat.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Terrorist Threat, Male Stereotypes, and Candidate Evaluations’, in Political Research Quarterly.

Featured image image Credit: Jagz Mario

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1T7vj7T

_________________________________

Mirya R. Holman – Tulane University

Mirya R. Holman – Tulane University

Dr. Mirya R. Holman is Assistant Professor of political science at Tulane University where she teaches and conducts research on gender and politics, research methods, and urban politics. She received her PhD in 2010 from Claremont Graduate University. She is the author of Women in Politics in the American City (Temple University Press, 2014). Her work has appeared in journals such as Political Research Quarterly, Political Psychology, Urban Affairs Review, Journal of Urban Affairs, and Social Science Quarterly.

Jennifer L. Merolla – University of California, Riverside

Jennifer L. Merolla – University of California, Riverside

Dr. Jennifer L. Merolla is Professor of political science at the University of California, Riverside and American Behavior Field Editor for the Journal of Politics. She received her PhD in Political Science from Duke University in 2003. Her research focuses on how the political environment shapes individual attitudes and behavior across many domains such as candidate evaluations during elections, immigration policy attitudes, foreign policy attitudes, and support for democratic values and institutions. She is co-author of Democracy at Risk: How Terrorist Threats Affect the Public (University of Chicago Press, 2009). Her work has appeared in journals such as Comparative Political Studies, Electoral Studies, the Journal of Politics, Perspectives on Politics, Political Behavior, Political Research Quarterly, Political Psychology, and Women, Politics, and Policy.

Elizabeth J. Zechmeister –Vanderbilt University

Elizabeth J. Zechmeister –Vanderbilt University

Dr. Elizabeth J. Zechmeister is Professor of political science and Director of the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) at Vanderbilt University. She received her Ph.D. from Duke University in 2003. Her research focuses on parties, representation, voting, public opinion, threat, disaster, corruption, among other topics. She is co-author of Democracy at Risk: How Terrorist Threats Affect the Public (University of Chicago Press, 2009); co-author of Latin American Party Systems (Cambridge University Press, 2010); and co-editor of The Latin American Voter: Pursuing Representation and Accountability in Challenging Contexts (University of Michigan Press, 2015).