People see insecurity as a bigger problem than the state of the economy, write Laura Jaitman and Stephen Machin.

People see insecurity as a bigger problem than the state of the economy, write Laura Jaitman and Stephen Machin.

Crime and violence are of major concern in Latin America and the Caribbean. One in four citizens in the region claim that insecurity is the main problem in their lives, even worse than unemployment or the state of the economy. While the region is home to fewer than nine percent of the world’s population, it accounts for 33 percent of the world’s homicides. The annual homicide rate of more than 20 per 100,000 people – more than three times the world average and 20 times the rate for the UK – makes the region one of the most dangerous places on Earth.

On average, six out of ten robberies in Latin America and the Caribbean are violent. While levels of violence are very low or at least decreasing in many parts of the world, this is the only region where violence remains high and, since 2005, has been intensifying. Crime leads to costly behavioural responses to mitigate the risk of victimisation and to cope with the pain and suffering.

Overall, crime imposes significant costs on the economy, absorbing at least three percent of the region’s economic output at a conservative estimate. The total cost of crime is high and comparable to the amount the region spends annually on infrastructure or to the share of income of the poorest 20 percent of the people in the region (Jaitman, 2015).

Is crime too high in Latin America and the Caribbean?

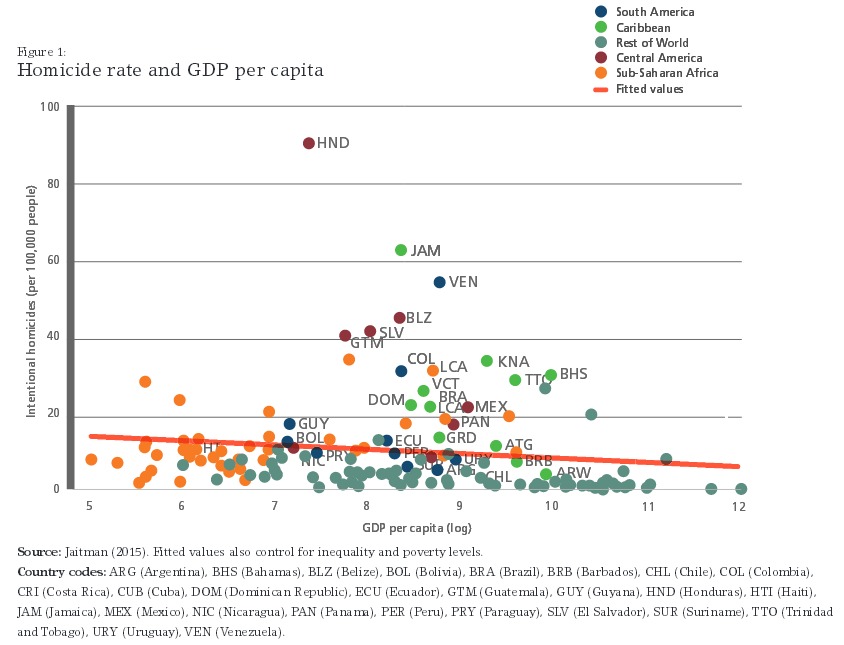

The region is an outlier in terms of crime if we take account of the wealth, inequality and poverty level of its countries. Figure 1 relates the homicide rate to the wealth of countries measured by GDP per capita. It is usually accepted that the higher the income of a country, the lower the incidence of violence. The red line, which shows the partial correlation of the homicide rate and GDP per capita (controlling for inequality and poverty), confirms this negative relationship.

But looking at countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, most of their data points lie far above the line. Thus, the region is an outlier for crime given its income level, as its countries’ homicide rates are higher than would be expected given their income levels (and which is not explained by the fact that countries in the region might be poorer or more unequal).

Predictions from the economics of crime

The framework of crime economics is a very useful tool for analysing the drivers of crime in Latin America and the Caribbean. According to this body of research, which began with the work of Gary Becker (1968), potential criminals assess the benefits and costs of committing crimes, compare them with those of legal activities and choose accordingly.

Although there are 300 police officers per 100,000 people in the region (compared with a figure of roughly 200 in the United States), widespread impunity makes the expected costs of committing crimes very low. For example, fewer than 10% of homicides in the region are resolved; and the justice system is very inefficient with about 60% of the prison population in pre-trial detention on average.

From the perspective of the benefits of legal activities, there is a great deal of scope for improvement. School enrolment rates are very high (around 93% in primary schools and 70% in secondary schools) but the region is lagging behind in the indicators of quality of education. The eight Latin American countries that participated in the latest Programme for International Student Assessment are ranked among the worst, and many young people are not well prepared for the labour market.

All of this suggests that to improve the situation, a portfolio of interventions is needed to increase the payoff to legal activities, together with crime control strategies that deter crime and violence.

Promoting evidence-based crime prevention strategies

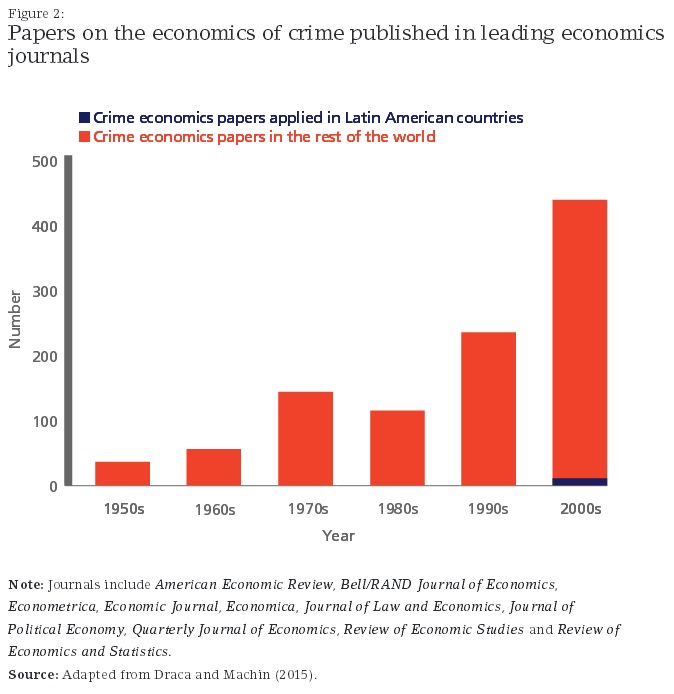

A sound research agenda on citizen security is critical to guide policies in this area. Although research on crime economics has been growing in the developed world, in Latin America and the Caribbean, crime remains an under- studied area (see Figure 2).

But conducting rigorous research on citizen security programmes is difficult in the region. One challenge is political: security in the developing world is a sensitive topic closely related to public opinion and political concerns. Citizen security interventions are often driven by politics, dogma and emotions. The dissemination of research projects is frequently obstructed when they run counter to established political gains, expose corruption or simply are considered by political operators to undermine society’s perception of security. The high rotation of public servants in this area also precludes longer-term research projects.

But perhaps the most evident problem is deficient information systems, which result in scarce and unreliable data. Crime statistics in the region are fragmented, inconsistent and aggregated only to the most macro levels. The lack of information and weak national statistics systems on crime thwart accurate diagnosis, monitoring and evaluation of crime and the interventions to counter crime.

Research conducted in Latin American contexts has shown interesting but scant results so far (see Jaitman and Guerrero Compean, 2015a for a comprehensive review; and 2015b). For example, by increasing household income and by mitigating the impact of income shocks, conditional cash transfer programmes contribute to the prevention of crime and violence in Brazil, Colombia and Mexico. And in Peru, the introduction of violence prevention and care centres for women has reduced the likelihood of domestic violence.

Research has also found that implementing urban renewal and neighbourhood improvement programmes and transit-oriented urban redevelopment connecting isolated low- income neighbourhoods show promise, but further research is required. There are several studies suggesting that police presence can deter crime and disorder: both hotspot policing and community policing show significant success in reducing homicides and fear of crime in Chile and Colombia.

Issues relating to police organisation are very important for the region, and research in Brazil has found that the integration of police forces’ operations leads to increased efficacy and reductions in crime. Finally, programmes based mainly on fear or military discipline reveal no appreciable impact on recidivism, but results show promise in electronic monitoring, reducing relapses in criminal behaviour in Argentina.

Gaps in knowledge about crime prevention

There remain many gaps in knowledge about crime prevention efforts as many police strategies have yet to be rigorously tested. There is currently not a clear understanding of the evolution of the disaggregated crime patterns and the roots of these high levels of violence.

Furthermore, organised crime and drug issues might be exacerbating violence in some cities and specific contexts that need to be examined from a regional perspective.

The research agenda should also include assessing the effect of optimum curricula and multi-level behavioural interventions to prevent violence in youth at risk. For example, little is known about the effect of combining education or employability training with life skills to strengthen resilience to crime. Another area of vital importance is the study of violence against women.

On policing, the emphasis should be on the role of police in terms of deterrence rather than incapacitation, because the latter necessarily requires higher imprisonment rates and overcrowding in prisons is recurrent. It is still unclear which are the main components of successful police reforms in the region. For example, community policing and problem-oriented policing are being pursued in many countries and are worth studying. Police investigation is also a key area with room for improvement.

Finally, in terms of criminal justice, a solid body of evidence is needed on the effect of imprisonment and most forms of extreme disciplinary mechanisms, particularly the effects on minors and low- risk individuals. Research on the use of alternative approaches to prosecution – such as electronic monitoring, community work programmes, drug courts, restorative justice meetings, cognitive behavioural therapies and re-entry initiatives – are promising areas for future research.

Featured image credit: DesignRaphael Ltd, for CentrePiece Magazine (edited to fit LSE USAPP’s size and format)

This article was originally posted on LSE Business Review, and is based on the article Crime and violence in Latin America and the Caribbean: towards evidence-based policies, published in CentrePiece, the magazine of LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance (CEP).

CEP and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) co-organised the 7th Transatlantic Workshop on the Economics of Crime in London in October 2015. The workshop included a special session on crime in Latin America and the Caribbean, an area in which the IDB is actively promoting crime prevention and control strategies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1M01TCz

_________________________________

Laura Jaitman – Inter- American Development Bank

Laura Jaitman – Inter- American Development Bank

Laura Jaitman leads the citizen security and justice research programme at the Inter- American Development Bank (IDB) in Washington DC.

Stephen Machin – LSE CEP

Stephen Machin – LSE CEP

Stephen Machin is Professor of Economics at University College London and and research director at LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance (CEP). His expertise is in labour market inequality, economics of education and economics of crime.