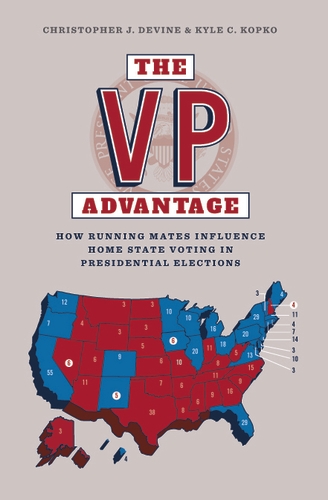

When it comes to US elections, a perception exists that a vice presidential (VP) running mate can help to deliver their home state’s electoral votes. But is this presumption of a VP ‘home state advantage’ correct and does it have the power to influence the eventual result? In The VP Advantage: How Running Mates Influence Home State Voting in Presidential Elections, Christopher J. Devine and Kyle C. Kopko undertake a quantative analysis to suggest that such an advantage is, in fact, relatively rare. While those interested in the impact of VP candidates on presidential elections will welcome this book, Richard Berry is left wondering as to where the potential value of vice presidential running mates actually lies.

The VP Advantage: How Running Mates Influence Home State Voting in Presidential Elections. Christopher J. Devine and Kyle C. Kopko. Manchester University Press. 2016.

The veepstakes are upon us. As an intriguing and somewhat traumatic presidential primary season approaches a conclusion, speculation about who the Republican and Democratic nominees will choose as their vice presidential candidates will begin in earnest. Christopher J. Devine and Kyle C. Kopko’s well-timed book is designed – through a systematic exploration of electoral and opinion data – to help them make that choice.

The veepstakes are upon us. As an intriguing and somewhat traumatic presidential primary season approaches a conclusion, speculation about who the Republican and Democratic nominees will choose as their vice presidential candidates will begin in earnest. Christopher J. Devine and Kyle C. Kopko’s well-timed book is designed – through a systematic exploration of electoral and opinion data – to help them make that choice.

The primary task the authors set themselves is to discover whether the home state of a vice presidential (VP) candidate has any bearing on the outcome of a presidential election. Is there a VP ‘home state advantage’ for the entire presidential ticket? Their overall conclusion – spoiler alert – is swift and decisive. As they state in the preface to the book:

Our conclusion, based upon the research in this book, can be summarised as follows: there is so little chance of a vice presidential home state advantage making a meaningful electoral difference that presidential candidates are far wiser, and more responsible to their constituents, to discount such strategic considerations… (xv)

Before embarking on their quantitative analysis, Devine and Kopko are at pains to point out that the assumption of a VP home state advantage is endemic in US politics. In Chapter Two, they cite numerous media articles claiming that particular veep contenders can help ‘deliver’ their home state for a presidential ticket. For instance, many commentators considered Marco Rubio a good option for Mitt Romney in 2012 because he is from the swing state Florida (12-14). This perceived advantage is rather belied by the fact that Rubio lost Florida by a huge margin to New Yorker Donald Trump in the recent Republican presidential primary.

More intriguing is Chapter Three’s discussion of how assumptions of a VP home state advantage influence the decisions made by presidential campaigns. The authors consider accounts from campaign insiders and analyse data on spending and appearances to prove this influence. For instance, after John Kerry chose North Carolina’s John Edwards in 2004, he campaigned heavily in the state (41-42). In 2008, meanwhile, Barack Obama cancelled planned activity in Alaska after sitting Governor Sarah Palin was announced as John McCain’s running mate (42-43).

Image Credit: Barack Obama with his running mate Joe Biden, 2008 (Daniel Schwen)

Image Credit: Barack Obama with his running mate Joe Biden, 2008 (Daniel Schwen)

The authors leave us in no doubt that, in almost all circumstances, campaign decisions such as these have no basis in electoral reality. This conclusion is rigorously confirmed in Chapter Four through quantitative analysis of election data ranging from the earliest presidential elections to the most recent, concluding:

The evidence presented thus far directly challenges the belief… that vice presidential candidates can be expected to deliver an electoral advantage in their home state. Across multiple time frames and methods of analysis, our consistent finding is that the average vice presidential home state advantage is statistically indistinguishable from zero. (79)

Building on the electoral data, Devine and Kopko introduce individual-level data into this debate for the first time, from the American National Election Studies surveys, in Chapter Four. This serves to enrich the analysis by adding insights into individual voters’ perceptions of vice presidential candidates. Ultimately it supports the conclusions suggested by the election data.

This might make disappointing reading for Hillary Clinton, Ted Cruz, Bernie Sanders and Trump, as they each consider how to maximise their chances of reaching the White House. But there is hope. While dismissing the impact of a VP home state advantage in general, Devine and Kopko spend much of the book detailing exactly how and when a home state advantage might come into play. Two key conditions have to be met: first, the state has to be small, and second, the VP candidate must have a long record of political service in the state. Both conditions must be met to allow for a ‘friends and neighbours’ effect to give the presidential ticket a small boost in that state:

…we do not deny the vice presidential home state advantage altogether but rather treat it as conditional; a significant advantage is likely if the running mate: (1) comes from a relatively less populous state; and (2) has extensive experience in elected office within that state. It is because most running mates do not meet this criteria that we observe a general null effect. (111)

These conditions have been met a number of times. For instance, Dick Cheney probably boosted George W. Bush’s vote in Wyoming in 2000 and 2004. However, as the state was certain to vote Republican anyway, this made no difference to the election outcome (135-36). In fact, the authors do not find a single instance of a president being elected thanks to an electoral boost in the home state of their running mate. This includes Lyndon Johnson, widely believed to have delivered his native Texas for John Kennedy in 1960. Johnson may have been an astute VP choice for a variety of reasons, but according to Devine and Kopko’s analysis, there is no evidence he had decisive electoral impact in Texas.

The authors find one instance where a losing presidential candidate might have won, had they chosen another running mate capable of capitalising on a home state advantage in a swing state. It’s one that will make liberals wince: Al Gore in 2000. Gore chose Joe Lieberman, from safely Democratic Connecticut. If instead he had opted for Governor Jeanne Shaheen from New Hampshire – someone he was actively considering – the phrase ‘hanging chad’ may have never entered the political lexicon. New Hampshire was small enough, and Shaheen experienced enough, that she might have overturned Bush’s 1.36% victory over Gore in the state. This one state would have been sufficient to give Gore a majority in the Electoral College.

Those looking for a comprehensive assessment of the impact of VP candidates in presidential elections will welcome this book, but they will also need to look elsewhere. The authors are narrowly focused on just one aspect of this topic. Given the prevalence of the assumption of a VP home state advantage, they clearly feel this is justified. The study is certainly fruitful, in disproving that assumption so comprehensively. It is no criticism to say that it leaves the reader with one burning, unanswered question: if geography doesn’t determine the potential value of a VP candidate, what does?

This review originally appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1VJUgHI

——————————————–

Richard Berry

Richard Berry is a Research Associate at Democratic Audit. He is also a scrutiny manager for the London Assembly and runs the Health Election Data project at healthelections.uk. View his research at richardjberry.com or find him on Twitter @richard3berry. Read more reviews by Richard Berry.