Among the growing discussions about race, justice, inequality and incarceration there has been a greater concern over the financial obligations placed on those who are convicted of crimes. In new research, Caterina G. Roman and Nathan W. Link examine the effects of ongoing child support payments on incarcerated fathers after their release, finding that less than a third had their payments changed whilst in prison, and that over 90 percent had payments in arrears after release. They argue that the multiple social services involved with incarcerated fathers both pre and post imprisonment need to provide more coordinated support so that child support orders do not become unwieldy, burdensome arrears.

Among the growing discussions about race, justice, inequality and incarceration there has been a greater concern over the financial obligations placed on those who are convicted of crimes. In new research, Caterina G. Roman and Nathan W. Link examine the effects of ongoing child support payments on incarcerated fathers after their release, finding that less than a third had their payments changed whilst in prison, and that over 90 percent had payments in arrears after release. They argue that the multiple social services involved with incarcerated fathers both pre and post imprisonment need to provide more coordinated support so that child support orders do not become unwieldy, burdensome arrears.

The intensifying discussions about race, justice and inequality spurred by police shootings around the United States have begun to focus some attention—as in Ferguson, Missouri—on the excessive and arguably unjust financial costs that individuals convicted of crimes often incur. These criminal justice-related financial obligations, such as court costs, fines, and fees for confinement, probation, and program participation, can create a serious debt burden that has unintended consequences for those that are convicted. Surprisingly, however, little attention has been given to the increasing debt fathers returning from prison might face due to child support obligations.

There are several reasons why child support obligations and related debt among formerly incarcerated fathers are important issues. First, child support payments play a significant role in the financial well-being of millions of American children. The US child support enforcement program had 15.7 million cases in 2012. For families receiving child support, Census data show that receipts per family averaged US$5,135 per year. This is significant for poor families because support payments can be roughly 40 percent of the family’s income.

Second, for fathers with child support orders, the monthly payments can be unrealistically high; studies suggest that payments for economically disadvantaged fathers often range from 20 percent to 35 percent of take-home income. For orders that go unmodified during incarceration, debt will mount quickly. One state-based study found that a quarter of all child support arrears owed to custodial parents was owed by individuals who were incarcerated or previously incarcerated. Third, having an understanding of the obstacles related to large debt burdens could assist prisoner reentry planning.

With the intent to go beyond anecdote or single-state studies in decribing the issue, we examined the prevalence of child support debt, service needs and receipt of child and employment-related reentry services among returning state prisoners using longitudinal data that were part of a national evaluation of the Serious and Violent Offender Reentry Initiative (SVORI), a comprehensive prisoner reentry program for serious and violent offenders in 12 states. Child support–related services were not a mandated part of the SVORI services in program sites, but it is likely that some participants received child support-related services because of the dedicated reentry resources provided to participants. Our focus was not only on services specifically related to having a child support order, but also on those services that would be indirectly related to supporting the financial welfare of a father, such as legal assistance, financial assistance, support getting employment documents (such as a birth certificate or or photo ID), assistance finding a job, and money management.

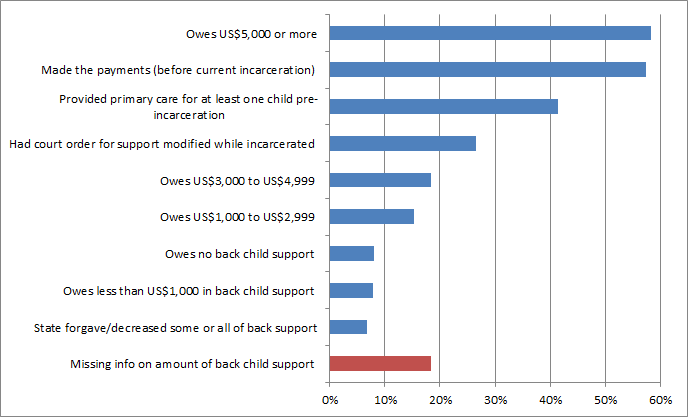

We used two waves of SVORI data—respondents that were interviewed at approximately 30 days prior to release from prison and 3 months post release. Not surprisingly, we found that a substantial number of returning state male prisoners in the sample had wide-ranging legal and financial needs due to having active child support orders. Of the men reporting having minor children in the SVORI sample, only 31 percent were required to pay child support during the 6 months prior to incarceration. As Figure 1 shows, of these only 57 percent reported having made the payments. The overwhelming majority (92 percent) owed back support (i.e., had arrears). Only a quarter (27 percent) of the sample had their child support orders modified while they were incarcerated. For more than half the sample, child support debt was very high—58 percent owed US$5,000 or more in back child support. Because of data limitations, we could not specify mean or median arrears, but one single-state study found that median arrears for formerly incarcerated prisoners were US$11,554, with a range from US$32 to US$108,394.

Figure 1 – Characteristics of men with child support obligations

For fathers in the SVORI study with child support obligations, some of the indicated needs were in critical areas for successful reentry and encouraging desistance, such as job training, and assistance finding employment. However, few received services to address these needs. Indeed, over three quarters of fathers with child support obligations reported needing job training services, yet less than 17 percent received any training during their first three months out. An even wider gap, 87 percent reported needing assistance with child support modification, yet only 12 percent were assisted. At three months post release from prison, these fathers ranked needing child support modifications as the third highest need—a jump up from sixth highest at baseline (i.e., a few months prior to release). This pattern suggests that these men are cognizant of their familial responsibilities and are likely struggling with making payments.

On a positive note, we did find evidence that the SVORI intervention was more successful than “business as usual” in delivering services to those returning fathers in need of child support services: those that were in the SVORI program group were much more likely to receive a higher number of child support–related services than those respondents who did not receive the SVORI treatment. Importantly, this treatment assignment was a far better predictor of child support–related service receipt than having a child support obligation itself. This was probably because SVORI treatment participants were much more likely to have completed needs assessments after release than non-SVORI participants. However, stating one’s needs and/or completing a needs assessment clearly was not sufficient to trigger service provision targeted to the array of reentry needs.

A key take-away point is that debt associated with child support arrears is not simply a criminal justice matter, but one that affects—and is affected by—multiple social services. As such, we hope these findings spur coordinated efforts among family and criminal courts, corrections, and child welfare systems more broadly. From a prevention standpoint, services to support noncustodial fathers should begin outside of the corrections system, before incarceration, so that child support orders do not become unwieldy, burdensome arrears in the event of incarceration. Court-based programs that can intercept soon-to-be-incarcerated fathers can help to provide support for possible modification of support orders. These efforts cry out for integrated or “cross-systems” data that could help identify the need and prioritize planning. Given the extent of unpaid obligations that could support high poverty families and children, policymakers might begin to think differently about how to prioritize support for returning prisoners and their families—a result that could yield healthier communities.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Community Reintegration Among Prisoners With Child Support Obligations An Examination of Debt, Needs, and Service Receipt’ in Criminal Justice Policy Review.

Featured image credit: Neil Conway (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1YH59tc

______________________

Caterina G. Roman – Temple University

Caterina G. Roman – Temple University

Caterina Roman is an Associate Professor in the Department of Criminal Justice at Temple University. Her research interests include the relationship between neighborhood characteristics, fear, violence, and health; the social networks of high risk and gang youth, and evaluation of innovative violence reduction programs. Dr. Roman is particularly interested in how the physical and social environment intersects with personal characteristics to influence how people use public spaces, and in turn, how physical activity is associated with individual and community health.

Nathan W. Link – Temple University

Nathan W. Link – Temple University

Nathan Link is a Ph.D. candidate in Criminal Justice at Temple University. He researches issues in U.S. corrections and criminal justice policy, and recently he’s been thinking about financial debt emerging from justice processes. His work is published in Justice Quarterly, Crime & Delinquency, and Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research.