Shrinking public finances have meant many cities and municipalities have looked to cut costs, with education not being spared. In new research, Jin Lee and Christopher Lubienski examine the effects of Chicago’s school closures, which have been justified by falling enrollment numbers. They write that schools in poorer areas are often likely to be the first targets for closure, a trend which means that there are fewer schools available for children – often African American and Latino – in less advantaged neighborhoods.

Public schools in the US are increasingly being shut down when they have been identified as underperforming on the basis of test scores and graduation rates. The traditional approach to school closure has been to reduce financial losses caused by empty classrooms and under-enrolled schools, especially in rural school districts. Indeed, this classic approach to maximizing efficiency is now evident in school closure policies in larger cities which are experiencing out-migration and depopulation. But now it has been combined with the idea of punishing apparent organizational underperformance.

The Chicago Public Schools (CPS), the third largest school district in the United States, is no exception. Chicago announced in the spring of 2013 that 54 primary schools would close in the upcoming school year, and that economies of scale provided justification for determining which schools to be closed. Considering that the number of primary school-age children has decreased by 24 percent in Chicago over the last decade, it is not surprising that school closures were accelerated in particular areas experiencing this decline. However, it is important to think carefully about where schools are closed and how that may impact students in terms of spatial equality.

In new research, we examine the possibility that school closings shape inequitable access to schools particularly for children in less advantaged neighborhoods. By taking into account travel time to schools, our study finds the CPS school closing policy—based on the capacity and the number of empty seats at schools—raises the likelihood that students in segregated communities have less access to neighboring schools.

Beware of location!

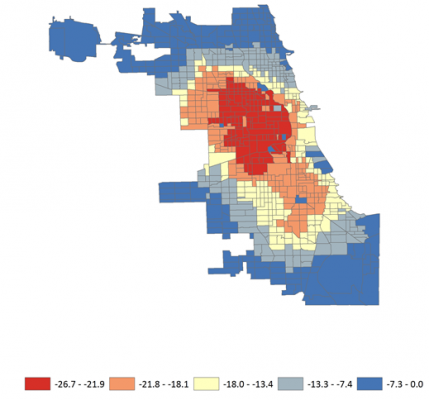

CPS has closed schools before. Chicago can close a school if the student enrollment is less than 80 percent of ideal enrollment. Thirteen primary schools were indeed closed for underutilization between 2001 and 2006, despite continuing debates over harms and benefits of school closings in large urban school districts. Yet, the reason that the latest school closing move in the fall of 2013 attracted such unwelcome attention is because of the scale: Chicago closed and relocated about 8 percent of schools. As shown in Figure 1, a substantial decrease in access to neighboring schools after these mass school closures occured in the north of downtown Chicago.

Figure 1 – Access change after the school closures

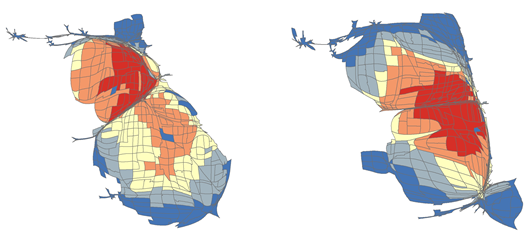

More precisely, the policy produced a notable change in access in areas with a high density of both African American and Latino American children. This suggests that school closures may be depriving students in particular areas of the opportunity to attend more convenient neighboring schools. As shown in Figure 2, the areas with a relatively large population of minority children are gradated in orange and red colors. This tells us that children in these areas experience significant declines in access after school closures.

Figure 2 – Access change by African American (left) and Hispanic (right) children

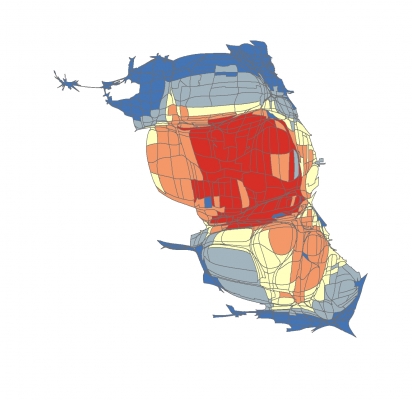

In Chicago, when neighborhood schools close, one of the the biggest potential problems is that children relocated to other schools may have to travel through dangerous neighborhoods. Parents with young children worry about such safety issues highlighted by greater distance and travel time between school and home. Figure 3 illustrates that children in dangerous communities feel the threat of significant change in access after the school closings. School closure policies force children in communities with high incidence of crime to travel further through the neighboring areas with higher crime rates.

Figure 3 – Access change by crime incidence

Locational disadvantage

Our representations of children disadvantaged by school closures demonstrate that enrollment-based school closings in urban school districts have selective impacts which are felt unequally across a city. Consistent with our research, community activists filed complaints under Title VI of the US Civil Rights Act in 2014, alleging that recent school closures in the three large urban districts of Newark, New Orleans and Chicago deny equal opportunities for African-American students. Here, the emerging question is how space-neutral school closings undermine spatial equality of educational opportunities.

Although cities are home to huge populations with diverse backgrounds, demographic and socioeconomic characteristics are not evenly distributed across all areas. In contrast to perspectives that cast geography as produced by natural and neutral causes, we see differences in demographic and socioeconomic characteristics affecting decisions, such as where to reside, or how to get to school. Subdivided geographies determine and furthermore reproduce locational advantages and disadvantages. As a common example, there are urban “ghettos” created by the geographic isolation of at-risk populations in inner cities. These sections of large cities have a long list of problems and threats, such as poor job markets, high rates of crime, and deficient access to public services, including public libraries. Rising gaps within and between neighborhoods involve declines in population, and school-aged population as well as increases in vacancy rates.

For urban school districts that plan to close schools in an attempt to save money, schools located in poor areas are often the first targets to be eliminated or consolidated. Consequently, this process leads to the loss of community schools for children who already reside in less advantaged neighborhoods. Current school closures, which tend to neglect underlying spatial contexts in urban cores, expose children in racially segregated and highly insecure communities to a double trap by lowering their ease of access to schools.

This article is based on the paper, ‘The Impact of School Closures on Equity of Access in Chicago’, in Education and Urban Society.

Featured image credit: Phil Roeder (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1sjJ9uZ

______________________

Jin Lee – University of Illinois

Jin Lee – University of Illinois

Jin Lee is a graduate student in the Department of Education Policy, Organization and Leadership at the University of Illinois. She is currently completing her doctoral program in education policy studying equity and access.

Christopher Lubienski – University of Illinois

Christopher Lubienski is a professor of education policy and Director of the Forum on the Future of Public Education at the University of Illinois. His research focuses on the intersections of public and private interests in education in areas such as school choice, charter schools, voucher programs, and home-schooling, as well as in education policymaking.

2 Comments