One of the major casualties of the 2016 election season has been the reputation of political science, a discipline whose practitioners had largely dismissed Donald Trump’s chances of gaining the Republican nomination. Lloyd Gruber describes just how wrong political scientists were about Trump, and explains why they should have been able to predict his success. Looking ahead to the fall general election, he questions whether voters will want Trump’s trigger-happy fingers on America’s nuclear button and suggests the remoteness of a Trump presidency is what had made it safe for primary voters to support him.

One of the major casualties of the 2016 election season has been the reputation of political science, a discipline whose practitioners had largely dismissed Donald Trump’s chances of gaining the Republican nomination. Lloyd Gruber describes just how wrong political scientists were about Trump, and explains why they should have been able to predict his success. Looking ahead to the fall general election, he questions whether voters will want Trump’s trigger-happy fingers on America’s nuclear button and suggests the remoteness of a Trump presidency is what had made it safe for primary voters to support him.

As a political scientist, I feel I owe you an apology. To say my discipline has been behind the curve this electoral season would be putting it too charitably. We haven’t missed one curve yet. We’re speeding through all of them – backwards. At the beginning of this year’s US presidential campaign we confidently assured you that the Trump phenomenon wouldn’t last, that the Republican base was just having a little summer fling. We told you we knew how presidential primaries worked. We’d studied them for years, knew the incentives, the structural dynamics, the statistical patterns. Been there, analysed that.

But Trump was just the first curve. Ever since the race started, we political scientists have been swerving, and colliding, into political reality. The only prediction I can responsibly offer – with 95 percent confidence – is that we will get it wrong again before it is all over. For what it’s worth – 5 percent? – I think I can already guess where we poli-sci geeks will go awry in the coming months. But before I get to my (very unscientific) prediction, I want to take a quick, humility-inducing look back at my discipline’s track record over the past six months and consider what we got almost-exactly wrong.

Let’s start with The Donald, shall we? The durability of Trump’s support has been this presidential campaign’s biggest shocker so far. But while it is tempting to focus on Trump – and that would certainly be his focus – the withering of support for the Republican Party’s establishment candidates was the flip side of Trump’s success. Why did Jeb Bush and Marco Rubio flame out in such spectacular fashion? And more to the point, why didn’t anyone in my discipline predict it?

Maybe it’s the rage, stupid. Or more specifically, the animosity toward immigrants, even though America used to be held up as a beacon for oppressed people around the world. That used to be why America was great. The Republican base may never have been especially welcoming toward Hispanics or Muslims, but Trump’s candidacy has tapped into a well of hostility toward these groups, a ferocity of nativist sentiment, that took political scientists by surprise. These sentiments may have been there all along, but now they are out there, for all to see (including many shame-faced Republicans who strongly reject these views). The discrimination is indiscriminate. Trump’s supporters rail against Hispanics and Muslims in general. They are all immigrants, immigrants are outsiders, and the outside world is a dangerous and menacing place. Keep it – keep them – out!

Again, the surprise isn’t the sentiment as such. The nativist views embraced by Trump’s supporters were not so different from the positions expressed by supporters of other Republican candidates, past and (until Texas Senator Ted Cruz dropped out of the contest) present. I doubt that Patrick Buchanan, a fixture of the party’s right flank during the 1990s, would have confessed his love for Hispanics – or the taco bowls made at the Trump Tower Grill – as ardently as Trump has recently done on Twitter. Trump’s protectionist leanings aren’t anything new either. Former Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee and Pennsylvania Senator Rick Santorum were of like mind, as was Pat Buchanan before them. But these were fringe candidates. Trump’s protectionist positions have gained traction in a way those (broadly similar) positions never did. This time it’s serious. And Trump’s supporters are seriously angry.

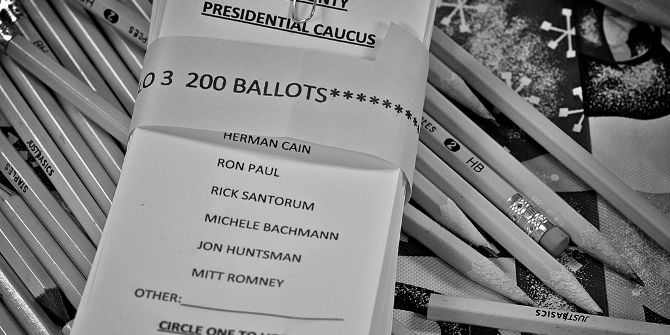

Credit: Jack Zalium (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-2.0)

We should have predicted this. What is political science, after all, but the study of power? It’s one thing for a country to be engaged in the world (and generous toward immigrants) when it’s the top dog, as the United States used to be – within the Western alliance at least – during the Cold War. The end of Cold War increased that favourable US-tilted power advantage even further. Presiding over a unipolar world order is nice work if you can get it. And with such a big lead over its rivals – and the capacity to “go it alone” if it didn’t get its way – the US could well-afford to be nice. International relations scholars still debate the end of the Cold War. Heck, we’re still debating the end of the Peloponneisan War. We debate everything. But one thing we don’t debate – because it’s so blatantly obvious – is that the rise of China has shortened America’s unipolar moment. It wasn’t a unipolar century, or even a unipolar quarter-century. America’s post-Cold War top-dog hegemony lasted barely more than a decade. And now that our Unipolar Blip is over and our global power is waning, the world no longer bends as easily to our wishes. Why should it?

There are two possible responses to this new geopolitical reality. The two responses are mutually exclusive, but never mind – Trump embraces both.

The first is to withdraw from the world, to tell our trading partners that if they can’t play fairly (which is to say the way we want them to play, in accordance with our rules), we’re taking our marbles and going home. That’s response number one: We’re outta there. If we can’t rule the world, we don’t want to be part of it. And so immigrants had best get outta here, “our” country. Get out and stay out.

The second response is to vanquish the world’s new geopolitical status quo and reclaim American’s past glory, its global hegemony. How? It’s easy: by electing a president who commands events, someone who’s in charge, someone the world cannot possibly ignore. Trump is confident he is that man, uh … person. He’s never doubted it for a moment. Elect Trump and the world – even China – will beat a path to our door, just like they used to back in the days when America really was top dog. Trump makes it look that simple. He is nothing if not confident in his abilities. It’s that kind of kind of confidence the Republican base is craving, a larger-than-life Napoleonic figure riding to the rescue on a white horse – only the white horse is Trump’s private jet and this Napoleonic figure has a bigger ego.

On the Democratic side, Hillary Clinton’s vulnerability isn’t so surprising. She did some foolish things both while serving as Secretary of State (conducting official business on her personal email account) and after (accepting large speaking fees rather than donating them to charities like, say, The Clinton Foundation). And she is not exactly a captivating speaker. She is good with details, but the details aren’t what voters care about (see above). They aren’t looking for charisma per se; Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders isn’t charismatic. Democrats – like Republicans – are looking for someone who can inspire confidence, who can communicate a simple, easy-to-understand vision for the country. Obama had that in 2008: “Yes, we can.” Sanders has that today: “Feel the Bern!” But not Hillary. Obama joked recently that her slogan should be “Trudge up the hill!” I get the joke, but it’s not funny. Personally, I would love to see the Trudger-in-Chief become America’s first woman president. The fact that Hillary is a woman – that fact alone – should have galvanized support for her campaign. And yet her disapproval ratings are currently above 50 percent. This must go down [the hill] as the campaign’s second biggest surprise. The push-back against Hillary’s pro-free trade positions should not have been surprising, by the way. Nor should anyone be surprised if, once elected president, she U-turns (again) and reaffirms her support for NAFTA and the Trans Pacific Partnership.

After driving our models the wrong way through the Trump and Clinton campaigns, we arrived at – and immediately fell behind – yet another curve. The third bend is the Bern. Bernie Sanders isn’t a great speaker, he’s older than the hills, and he’s not even a Democrat. He’s a democratic socialist! I can still remember when Michael Dukakis, the Democratic presidential candidate in 1988, described himself as – yikes – a liberal. The very mention of the L-word was enough to sink his chances. And yet Bernie S-word Sanders still has a shot at capturing the Democratic Party’s nomination if he wins the California primary.That’s a big if, but this is 2016. I’d take that bet. So Sanders is either a serious contender or, if he doesn’t go gracefully, a serious spoiler. The surprise here is the rage on the left. There is a soak-the-rich mentality among young voters that looks more European than American. Maybe it has something to do with their disappointment in the Obama revolution. The revolution he was supposed to have sparked never came.

So what about now? Are the surprises over? Could anything else surprising happen between now and the election? I think the answer is yes: a Trump victory. If that happened, it would be like Leicester City Football Club winning the Premier League.

But seriously, the prospect of a Trump presidency is just that – serious. Still, as the election date draws closer and the size of the electorate expands, everything we political scientists know about electoral dynamics points to a Clinton victory.Primary voters didn’t need to worry that in casting a ballot for Trump they would be putting his trigger-happy fingers on America’s nuclear button. No one – not political scientists, not anyone – thought The Donald would make it as far as he has. The remoteness of a Trump presidency is what made it safe for primary voters to support him, or so I would (still very humbly) submit. Now that we are entering the last round of this year’s contest, there is no second chance, no fall-back position, if Trump makes it through. Almost no one adores Hillary Clinton the way Barack Obama’s supporters adored him back in 2008, but I would be shocked if American voters did not turn out in large numbers to support a predictable trudger over a brash and unpredictable braggart. That would be a curve too far.

And even more surprising than a Trump victory would be a successful Trump presidency! He would have to be a quick study and would need to rein in his instinctive belligerence. I would expect to see a lot more Executive Orders, even more than we have seen in Obama’s second term. So maybe Trump would succeed in breaking the logjam in Washington. I’d worry about what he would do once that dam was broken, but whatever he does, it wouldn’t last beyond the 2018 midterm election, when the Democrats would sweep to victory in Congress.

Gridlock would never look so good.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1TJvtzR

______________________

Lloyd Gruber – LSE International Development

Lloyd Gruber – LSE International Development

Lloyd Gruber is a Lecturer in the Political Economy of Development at LSE. A political scientist by training, he is the author of Ruling the World: Power Politics and the Rise of Supranational Institutions. His research interests include globalization, inequality, and redistribution; power and institutions; international and comparative political economy; trade’s impact on spatial disparities in economic and political development; regional integration and foreign economic policy; and public policy analysis. He has been an associate professor at the University of Chicago’s Harris Graduate School of Public Policy Studies as well as a visiting scholar at the Brookings Institution.

Political science isn’t a science, it’s an art… But don’t feel too bad, economics isn’t a science either, that study has been called worse — “the dismal science”, “common sense made difficult” — under current circumstances econ might best be labeled not even an art but a wild gyrating dance.

The Rise of Trump et al. and the Threats to Globalism are simply lessons in humility, to both now-elderly professions. Think the 1930’s, and Toynbee: we are having one of his times-of-troubles, now, really a time-of-paradigm-change — ours far more mild than our great-grandparents faced back then — one problem with creative-destruction is that it requires some destruction, the other is that what emerges from the ashes is less likely to resemble a phoenix than a Rough Beast.

That the new Rough Beasts are unrecognizable to The Established Professions goes without saying — yes they must deal-with-it, gingerly & stubbornly as Mmes. Yellen & Lagarde now are, coupling ad hoc solutions with firmness, but no more hiding behind calling themselves a science & re-using precise formulas which have not worked. Brave new worlds.

Political Science is a field of study that observe political phenomenon and generate views and analysis, come up with an idea and provide new theories, however it might be good to have an apology over a wrong way prediction of an unpredictable political candidate, but i just want to share my thoughts, as a baccalaureate degree holder of the discipline, I guess we forget the very essence of going back to basics, we tend to complicate things which sometimes lead to wrong interpretations, or we are not like a mathematicians that provides probabilities of exact or correct numbers. In the field of politics, we only give probabilities to the unpredictable phenomenon which we do not know the next exact directions. So don’t feel sorry sir, We aren’t perfect.

Have I missed something? I read this piece looking for a discussion of how it was that political science got Trump wrong, but there’s nothing here except a link to a faulty prediction by Nate Silver (a political scientist? not really), plus a whole lot of (very brisk and amusing) repackaging of already-known events. There is no discussion of what “our models” are exactly, or why they were faulty, or what might be done. There is a very interesting piece to be written about the failure to predict — and why should THAT be the standard against we are judged, precisely? — but this is not it. Alas.

This is silly and sloppy: political scientists do not all sing from the same chorus. The only single reference to who, exactly, got the predictions wrong was to Nate Silver, who is a statistical journalist and who has already published columns explaining why his expectations were erroneous.

By contrast, there are noted scholars and card carrying political scientists like Cas Mudde (Monkey Cage) and Matthew Yglesias (VoxPop) who argued as early as August 2015 (almost a year ago now) that support for Trump was not a passing phenomenon but was, instead, analogous to the popularity of the populist right in several European countries. There are many other examples. Analysis of survey data by orher colleagues supporting this interpretation has demonstrated the racist support for Trump – and the authoritarian values among his supporters.

See http://www.vox.com/2015/8/25/9203405/trump-european-far-right

http://015/08/26/the-trump-phenomenon-and-the-european-populist-radical-right/

So not all political scientists “got it right” but neither did other commentators.