Some studies have shown that addressing income inequality is gaining in popularity. Michelle Atherton and Wesley Leckrone explore whether concern for the poor is an item on the agendas of big cities. Their analysis of mayors’ State of the City (SOTC) speeches shows that attention to redistributive policy options is rare regardless of the demographic or ideological characteristics of a city. The past trend of focusing on economic development, and therefore growth, is still the predominant focus of US mayors. This is especially the case for poorer and more conservative cities.

Some studies have shown that addressing income inequality is gaining in popularity. Michelle Atherton and Wesley Leckrone explore whether concern for the poor is an item on the agendas of big cities. Their analysis of mayors’ State of the City (SOTC) speeches shows that attention to redistributive policy options is rare regardless of the demographic or ideological characteristics of a city. The past trend of focusing on economic development, and therefore growth, is still the predominant focus of US mayors. This is especially the case for poorer and more conservative cities.

Income inequality has increased dramatically over the last several decades. Since the late 1970s, the after tax income of the top 1 percent of Americans has increased 200 percent, while the middle 60 percent of the population and the bottom 20 percent have grown just 40 percent and 48 percent, respectively. Americans show little support for redistributive policies, but as the presidential campaign of Democratic Senator Bernie Sanders (VT) demonstrates, the politics of inequality is not lost on a significant portion of the electorate.

Traditionally, studies on inequality have investigated the divide between city and suburb, but with urban areas gaining population, attention has shifted to the effects of income inequality within cities. A recent Brookings Institution report on the 50 largest US cities showed the inequality within these communities exceeded the national average. Urban inequality has been linked to class and racial segregation, both with negative effects on mobility. Still, US cities are ill-suited to address issues of income inequality in the American federal system. Capital and taxpayers alike are free to move across jurisdictional boundaries leading to a competitive disadvantage for cities that take on increased taxes to provide additional services. Instead, agendas in cities typically focus on developmental policies to expand the tax base. Furthermore, the shift to a post-industrial service-based economy leads to the need to provide amenities to attract a desirable, highly educated workforce. Traditionally this type of new resident has been less likely to support redistribution, and less reliant on the provision of government services as they are able to create their own extra-governmental service structures (i.e., Friends of schools, parks, etc., and business and neighborhood improvement districts). However, there is evidence that concern for the poor may be emerging as part of a new post-material urban political culture that values diversity and inclusion. In new research, we examine whether or not this actually translates to the policy agendas of cities.

“A metropolitan economy, if it is working well, is constantly transforming many poor people into middle-class people, many illiterates into skilled people, many greenhorns into competent citizens.” – Nashville Mayor Karl Dean quoting urbanist Jane Jacobs in his 2013 SOTC

Our study looked at two major questions: 1) how prevalent are redistributive and economic development issues on mayors’ agendas, and 2) is the attention given to these issues differentiated by the characteristics of individual cities? These questions were tested using 138 State of the City speeches from 45 of the 50 largest cities in the US between 2010 and 2013 using the Policy Agendas coding scheme. This method allowed us to compare how much attention is given to a range of topics using exclusive and exhaustive categories. The speeches were then analyzed by exploring how mayors discuss issues of poverty and inequality and what types of cities paid attention to redistributive or economic development issues. Six city characteristics were tested to determine they affected the amount of attention devoted to these issues: racial demographics, level of segregation, poverty levels, median household income, ideology, and population.

While each SOTC address was unique, patterns did emerge. The speeches showed mayors weary from the Great Recession and embattled by declining own-source revenues as well as diminishing intergovernmental transfers. There was little call for expanding or starting large-scale government programs. Hard times called for shared sacrifice, and after years of cuts and ballooning pension payments, many declared there was nothing left to trim.

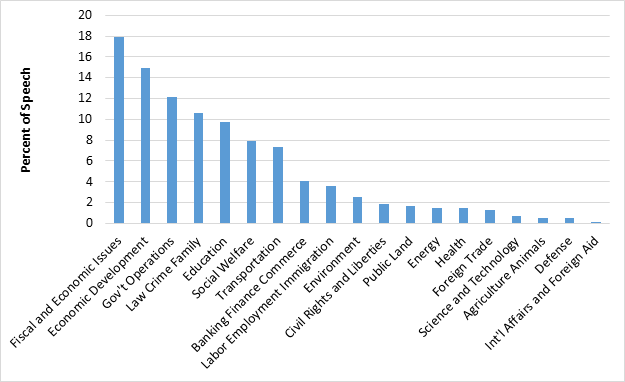

Figure 1- Percentage of mentions of policy codes 2013

As shown in Figure 1, fiscal and economic issues topped the list at 17.9 percent of policy content. This was followed by community and economic development (15 percent), government operations (12.2 percent), law crime and family (10.6 percent), and education (9.76 percent). Social welfare policies accounted for just 7.9 percent of the agenda, though they were sixth out of 18 possible policy codes. The top five issues are all traditional areas of policy undertaken by local government, and each is important to economic growth and/or attracting residents who will contribute to the tax base and demand little in the way of city services. Any direct mention of income inequality was rare. For many mayors, economic growth was the primary path toward eliminating poverty. Still, three main categories emerged as the means for dealing with poverty in the SOTC speeches. First, the closest to a large scale redistributive program was called for in San Francisco in the form of an Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). Second, public-private partnerships allow cities to leverage their revenue with that of non-profits and the for-profit sectors. Last, many mayors asked citizens to volunteer for programs the cities themselves thought worthy but were unable to afford.

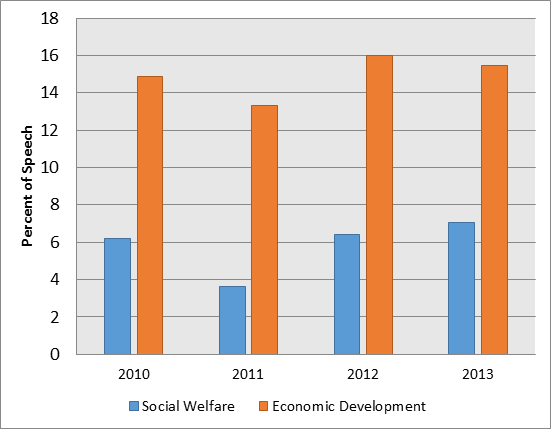

Figure 2 – Attention to social welfare and economic development 2010-2013

Consistent throughout each year of our study, community and economic development issues trumped the mention of social welfare issues by at least 200 percent, if not more, as in 2013. (See Figure 2) Community and economic development occupied the largest amount of the agenda in 2012 at 16 percent. These findings are in line with previous studies on cities showing little appetite for budgeting and spending on redistributive issues.

So, what types of cities pay attention to social welfare and economic development issues? Surprisingly, there is no differentiating factor for cities that put redistributive issues on the agenda. This finding runs counter to the emerging narrative that there is a new politics of progressivism developing in cities. Of course, such a culture might still exist, but there might be other factors at work. For example, mayors might not need to push for such an agenda from a progressive populace, and they might seek to satisfy demands for ending poverty through education and job training.

As for the economic development agenda, the results show that as segregation increases, attention to such policies declines. Meanwhile, poorer cities dedicate more agenda space to community and economic development issues. Along ideological lines, the more conservative the city, the more attention paid to development. Another interesting result shows that the percentage of nonwhite residents moderates the effect of the percentage of the agenda dedicated to economic development issues. In short, segregation has no effect on the economic development agenda in mostly white cities, but a substantial negative effect in cities with a mostly nonwhite population. Therefore, economic development matters less to mayors who run highly segregated and highly nonwhite cities. Perhaps because arguments for public goods like education and safety crowd out material concerns.

Economic inequality might be a growing topic of concern among the public. However, big city mayors spend very little time trying to enact programs specifically targeted at redistributing income. Rather, they focus on traditional economic development to attract business investment in the hope that a rising tide lifts all boats.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Does Anyone Care about the Poor? The Role of Redistribution in Mayoral Policy Agendas’, in State and Local Government Review.

Featured image credit: Lars Plougmann (Flickr, CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/29GnfM4

_________________________________

Michelle J. Atherton- Temple University

Michelle J. Atherton- Temple University

Michelle J. Atherton is the associate director of the Institute for Public Affairs at Temple University and the senior policy writer and editor at its Center on Regional Politics. She has authored and co-authored white papers on such topics as municipal government, legislative reform in Pennsylvania, education policy and finance, and public pensions, and co-authored articles in State Politics and Policy Quarterly and State and Local Government Review. Atherton also co-edited a volume of Commonwealth: A Journal of Pennsylvania Politics and Policy where she serves as an associate editor.

J. Wesley Leckrone – Widener University

J. Wesley Leckrone – Widener University

J. Wesley Leckrone is an associate professor of political science at Widener University. He is the editor of Commonwealth: A Journal of Pennsylvania Politics and Policy. His publications include articles in Publius: The Journal of Federalism, State Politics and Policy Quarterly, and the Journal of Urban Affairs.

1 Comments