Facing a gridlocked Congress, the last 18 months have seen President Obama make increasing use – as promised – of his “pen and phone” to implement policy via executive actions. While Obama has been roundly criticized from the right for taking such unilateral actions, do Americans instinctively oppose them? Using survey experiments to test this question, Dino Christenson and Douglas Kriner find little evidence that Americans oppose unilateral actions as threats to checks and balances. Instead, constitutional concerns are overwhelmed by partisanship and policy preferences. The means through which the president pursues his policy priorities – be it legislation or unilateral action – is largely irrelevant.

Facing a gridlocked Congress, the last 18 months have seen President Obama make increasing use – as promised – of his “pen and phone” to implement policy via executive actions. While Obama has been roundly criticized from the right for taking such unilateral actions, do Americans instinctively oppose them? Using survey experiments to test this question, Dino Christenson and Douglas Kriner find little evidence that Americans oppose unilateral actions as threats to checks and balances. Instead, constitutional concerns are overwhelmed by partisanship and policy preferences. The means through which the president pursues his policy priorities – be it legislation or unilateral action – is largely irrelevant.

Before his first cabinet meeting of 2014, President Obama fired a warning shot across the bow of congressional Republicans. If Congress failed to act on key priorities, Obama promised to act unilaterally: “I’ve got a pen and a phone. And I can use that pen to sign executive orders… that move the ball forward.”

And act unilaterally President Obama has. The administration’s unilateral moves on a range of issues from changing the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, to liberalizing the enforcement of immigration policy, to ordering unilateral airstrikes against Libya have produced fiery denunciations from politicians and pundits alike. While they may huff and puff, both Congress and the Courts often appear largely unable to prevent or overturn high profile executive actions (recent judicial challenges to Obama, notwithstanding).

The weakness of these formal legislative and judicial constraints led us to question elsewhere why presidents do not act unilaterally even more frequently? Indeed, with such a polarized political sphere and gridlocked Congress this may be the only way for presidents to accomplish their policy objectives. The answer, we argued, is that presidents also are concerned about the political costs of acting unilaterally. In particular, presidents hope to avoid provoking a popular backlash.

But do Americans instinctively oppose unilateral action? Some recent research suggests yes, and argues that super-majorities of Americans oppose presidents acting unilaterally to enact new policies without seeking congressional approval. A Vox article captures the sentiment of the piece: “It shows that Americans do, in fact, care about how presidents exercise their authority — and that they want limits on it, even when they support the individual at the helm.”

By contrast, our work suggests a much weaker and more conditional public constraint on the unilateral presidency. Instead of automatically recoiling against unilateral action as a threat to our constitutional system of checks and balances, we find that most Americans evaluate unilateral action through the same partisan cues and policy preferences that they use to make other political judgments.

Consider the results from our first experiment. All subjects were told that “President Obama has aggressively used unilateral executive power to pursue his priorities in both foreign and domestic policy.” Half of the sample received no additional information. The other half of the sample was told that Obama acted unilaterally because of the pervasive gridlock in Congress. All respondents were then asked whether they supported or opposed presidents using their “power in some cases to bypass Congress and take action by executive order to accomplish their administration’s goals.”

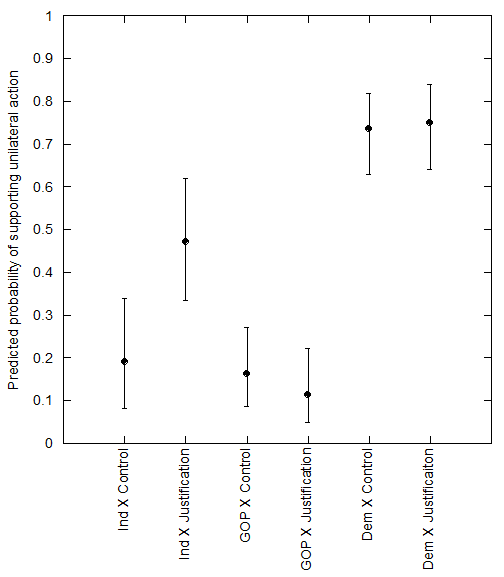

Figure 1 shows our main results. Rather than instinctually opposing unilateral action, subjects relied on partisan cues to form their assessments. Democrats strongly supported unilateral action and Republicans almost uniformly opposed it, regardless of whether or not a justification was given. Independents, who lack strong partisan priors, responded to the gridlock justification by becoming more supportive of unilateral action. In other experiments we find similar patterns in both domestic and foreign policy and when subjects evaluate unilateral actions taken by both George W. Bush and Obama.

Figure 1 – Predicted probability of supporting unilateral action by party affiliation

Note: Dots present present the predicted probability of the median partisan in each treatment group supporting unilateral action. I-bars present 95% confidence intervals.

In another pair of survey experiments, we described President Obama’s efforts to cap student loan payments and to reform the nation’s immigration system. Half of subjects were told that President Obama was pursuing the objective legislatively. The other half was told Obama was pursuing the same policy objective through unilateral action.

In both experiments, we found no evidence that the public instinctively opposed a unilateral approach. Indeed, in both cases the fraction of Americans supporting Obama was statistically indistinguishable across the legislation and unilateral action treatments.

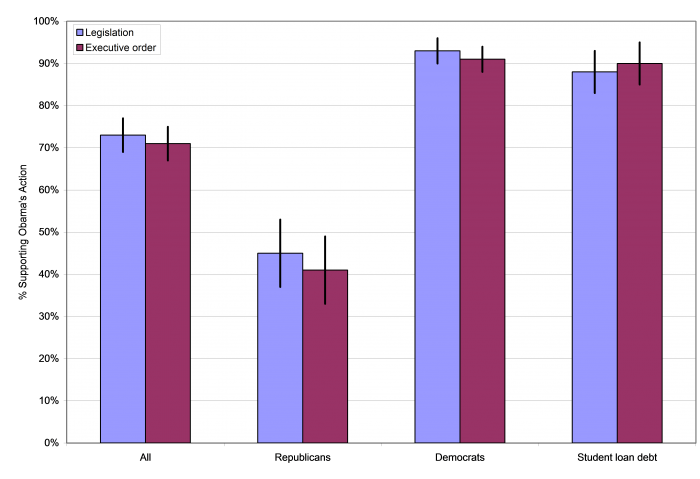

Figure 2 – Support for Obama legislative or executive action across subgroups

Note: Vertical lines illustrate 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2 plots support for Obama’s efforts to cap student loan payments by treatment across subgroups. A strong majority backed Obama’s efforts, regardless of whether he pursued his objective through legislation (73 percent) or unilateral action (71 percent). Republicans were much less supportive of Obama than Democrats. However, neither Republicans nor Democrats cared whether Obama pursued his objective unilaterally or legislatively. Finally, Americans with a direct stake in the fight – those with student loan debt – were more supportive of Obama’s efforts than other Americans. Moreover, these subjects also cared only about the policy end, not the means through which the president sought to accomplish it.

In short, when asked to consider concrete examples of unilateral action in the contemporary political arena, partisan forces and policy assessments all but overwhelm any underlying constitutional concerns. In our intensely polarized polity the dynamics driving public attitudes toward unilateral power are remarkably similar to those driving public opinion toward other policy actions. Consequently, our results suggest a weaker and more contingent public constraint on unilateral action.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Constitutional Qualms or Politics as Usual? The Factors Shaping Public Support for Unilateral Action’ in the American Journal of Political Science.

Featured image credit: The White House

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/29Mi3s5

_________________________________________

Dino P. Christenson – Boston University

Dino P. Christenson – Boston University

Dino P. Christenson is an associate professor of political science and a faculty affiliate of the Hariri Institute for Computational Science & Engineering. Christenson studies American political behavior, public opinion and quantitative methods.

Douglas Kriner – Boston University

Douglas Kriner – Boston University

Douglas Kriner is an associate professor of political science and the Director of Undergraduate Studies. His research interests include American political institutions, separation of powers dynamics, and American military policymaking.