For many crimes there is often a gap between when an arrest warrant is issued, and when a suspect is apprehended by law enforcement authorities. In new research using data from the National Crime Information Center Database, Sarah W. Craun and Andrew D. Tiedt analyze the time it takes for a warrant to be closed for various types of crimes. They find that while most warrants are closed in a little over a month, warrants for child pornography, child exploitation and violent crimes were more likely to be closed more quickly, as were those which allowed for full extradition or extradition from adjacent states.

For many crimes there is often a gap between when an arrest warrant is issued, and when a suspect is apprehended by law enforcement authorities. In new research using data from the National Crime Information Center Database, Sarah W. Craun and Andrew D. Tiedt analyze the time it takes for a warrant to be closed for various types of crimes. They find that while most warrants are closed in a little over a month, warrants for child pornography, child exploitation and violent crimes were more likely to be closed more quickly, as were those which allowed for full extradition or extradition from adjacent states.

Law enforcement agencies are forced to make difficult decisions on a daily basis about how to prioritize cases, thereby allocating resources to identify and apprehend suspects. This prioritization necessitates an understanding of how long it typically takes to close warrants. If a warrant goes stagnant, calling in assistance from outside agencies or taskforces may expedite the apprehension of a fugitive. However, this crucial information on the average time it takes to close warrants is not well documented, primarily due to difficulty accessing restricted law enforcement data.

Up until this time, a substantial portion of the literature examining the timing of an arrest of a suspect focused on clearance rates. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), for a crime to be cleared, a person must be identified as the main suspect for a crime, charged with a crime, arrested, and turned over to the court system. The focus of crime clearance research on all of these combined factors may provide an inaccurate picture for criminal justice practitioners and researchers. Separating the concepts of detection and arrest can allow law enforcement agencies to have an informed response to those offenders where a warrant has been issued for a crime, yet the offenders have yet to be apprehended.

The National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database, housed by the FBI, contains approximately two million warrants at any given time. We were in the unique position, as operationally-focused researchers employed by the federal government, to have access to the NCIC data. To determine the average time to warrant closure and predictors of the time to closure, we utilized data from a nine month time period in early 2014. We calculated the time to close a warrant by obtaining the difference between the date the warrant was closed and when it was entered into NCIC, as long as the warrant was not subsequently labeled as canceled.

We used statistical modelling to determine average time to close across the entire group, while also revealing what factors about the warrant and the offender change the predicted time to close. We looked at a variety of factors including the type of crime for which the warrant was issued, the extradition limits on the warrant, if the warrant was for a felony or a misdemeanor, if the warrant noted that the offender was armed and dangerous, and demographics about the offender.

When examining the group of warrants as a whole, we found warrants tend to be closed quickly after entry into NCIC, and if they remain open the rapid initial gains lose traction over time. For example, 17 percent of all warrants were closed within 7 days, and 29 percent were closed within 30 days of their entry date. If one looks 60 days after entry they would find 50 percent of warrants across the board were still open.

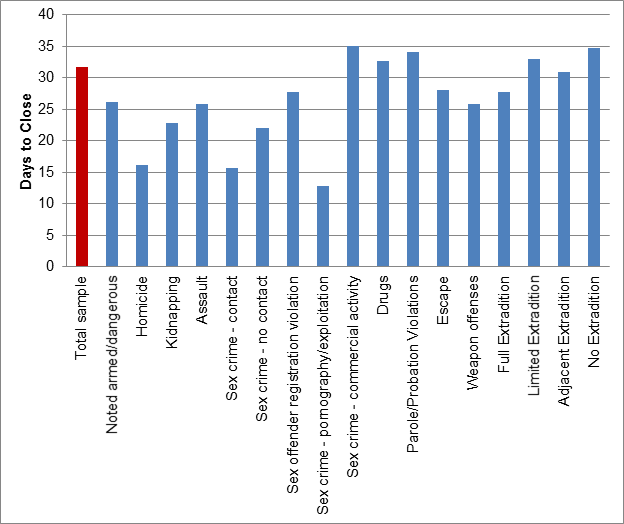

Figure 1 – Average days to close warrants on select variables

Source: National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database, Federal Bureau of Investigation

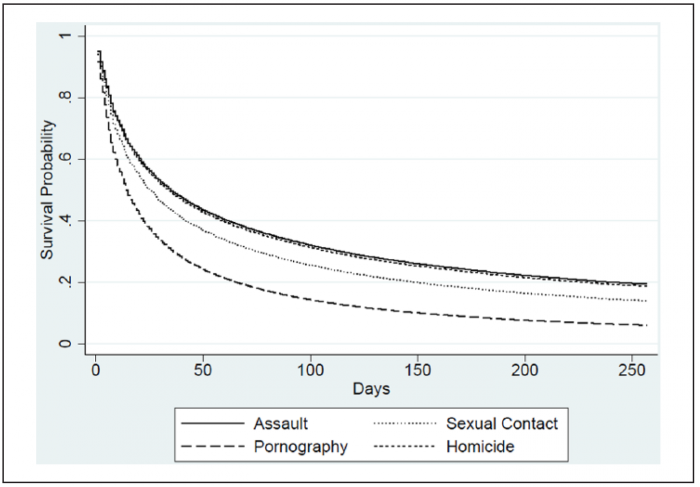

However, we would be careless if we assumed all warrants, and crimes for that matter, were of equal weight in the eyes of the public or law enforcement. Accordingly, we found some significant differences in closure times based on the crime for which the warrant was based. Warrants for child pornography/exploitation were likely to be closed quicker than any other crime type. At the end of the nine month study period, only 16 percent of child pornography/child exploitation warrants were still open as compared to almost 30 percent of the entire sample. Other crimes also led to quicker closure times including sex crimes with contact, sex crimes without contact, sex offender registration violations, assault, kidnapping and homicide. Beyond just the crime, being designated as armed/dangerous was related to quicker apprehensions by law enforcement.

Figure 2 – Projected time to close warrants for four selected crimes

Source: National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database, Federal Bureau of Investigation

Extradition also played a role, which is critical to understand. Those warrants that allowed for full extradition or extradition from adjacent states were closed faster than those without a possibility of extradition. In other words, it is not necessarily the work done by law enforcement, or the crime of the offender which impacts how quickly a warrant is closed. If warrants are limited in terms of extradition, offenders can move to geographies outside of these boundaries and continue their lives without being held responsible for their previous crimes. It could be that law enforcement that are located in resource-poor jurisdictions may be less likely to apprehend suspects if they cannot finance networks outside of their immediate jurisdictional boundaries. While determining how agency resources impact time to closure was beyond the scope of this paper, other research has found that a law enforcement agency’s expenditures do impact clearance rates.

Our findings suggest that while warrants are typically closed in little over a month, warrants that remain open for six months are much more likely to stay open. Law enforcement agencies clearly prioritize apprehension of suspects wanted for sex-related crimes and violent crimes. In some of these cases, particularly in respect to pornography/exploitation, agencies may have better access to identifying information that can be obtained via internet protocol addresses or gleaned from sex offender registries that increase the likelihood and speed of apprehension. Focusing on time to arrest as a quality measure exposes the complex processes that influence selecting individual cases on the local level and underscores the importance of collaboration between agencies. The results of our study imply that working to expand extradition would go a long way toward clearing back-logged cases.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Time to Apprehension and the Correlates of Warrant Closure’, in Crime & Delinquency.

Featured image credit: Connor Tarter (Flickr, CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Note: The opinions or points of view expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice, nor USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. The authors of the article were employees of the United States Marshals Service at the time this article was written, and the article is in the public domain.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2aGaCCG

_________________________________

Sarah W. Craun – National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime, Federal Bureau of Investigation

Sarah W. Craun – National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime, Federal Bureau of Investigation

Sarah W. Craun is the research coordinator for the National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime at the Federal Bureau of Investigation. She received her Ph.D. from the University of California – Los Angeles.

Andrew D. Tiedt – Office of Research and Evaluation, Federal Bureau of Prisons

Andrew D. Tiedt – Office of Research and Evaluation, Federal Bureau of Prisons

Andrew D. Tiedt, Ph.D., is a demographer who works for the Office of Research and Evaluation at the Federal Bureau of Prisons. He has published on issues ranging from recidivism of released prisoners to the impacts of population aging.