America’s roads are crumbling and underfunded. One possible solution to this funding crisis is the introduction of a vehicle-miles-traveled (VMT) tax, though this has been criticized as placing a greater burden on poorer drivers. In new research Di Yang, Eirini Kastrouni, and Lei Zhang examine the effects of an income-based VMT where those with higher household incomes pay more. They find that an income-based VMT is much fairer than a flat-rate tax, and also would not have a significant impact on how much people drive.

America’s roads are crumbling and underfunded. One possible solution to this funding crisis is the introduction of a vehicle-miles-traveled (VMT) tax, though this has been criticized as placing a greater burden on poorer drivers. In new research Di Yang, Eirini Kastrouni, and Lei Zhang examine the effects of an income-based VMT where those with higher household incomes pay more. They find that an income-based VMT is much fairer than a flat-rate tax, and also would not have a significant impact on how much people drive.

In 2007, the US Government Accountability Office placed the country’s road system on the High Risk List. Several factors have contributed to the critical condition of the system: unaffected federal motor fuel taxes, inflation, raised corporate average fuel economy (CAFE) standards and a higher market share of alternative-fuel vehicles. Despite these funding issues, construction and maintenance needs have not decreased. In 2012, the Congressional Budget Office estimated it would cost over $110 billion to maintain the present spending level through 2022.

To address the insolvency of the current funding system, alternative revenue sources should be considered in lieu of the fuel taxes. A fee or tax based on vehicle-miles-traveled (VMT) would be a desirable replacement for motor fuel taxes according to the National Cooperative Highway Research Program. By taxing the level of vehicle-miles-traveled rather than fuel consumption, we could ensure a more stable and sustainable revenue stream for the future.

However, VMT fees often raise equity issues; since lower-income drivers are more sensitive to increased driving costs, they are more likely to be priced off the road. Flat-rate VMT fees have been criticized for being regressive, placing a disproportionate financial burden on lower-income drivers. However, an income-based VMT fee may prove to be more effective. Similar to Seattle’s transit system, which will provide discounted fares to commuters whose household income is less than 200 percent of the federal poverty level, in new research, we explore the equity performance of an income-based approach that could potentially alleviate equity concerns.

Inspired by income and property taxes, we propose income-based variable-rate VMT fee structures in a bid to address the regressive nature of the current funding policies, while raising additional revenue for the surface transportation system. This means that higher-income households will be charged a higher VMT fee than their lower-income counterparts. Also, the proposed variable-rate VMT fees are designed to double the current fuel tax revenue level at the state level by 2020, following a recent study by the National Surface Transportation Policy and Revenue Study Commission. Three variable-rate VMT fee schemes are introduced: Ramsey pricing, fixed-interval incremental, and fixed-percentage incremental. Ramsey pricing is based on the “inverse elasticity rule,” where price margins are designed to be inversely proportional to the demand elasticity of a product or service. In this case, those with a higher willingness-to-pay (WTP) will pay more than those with a lower WTP. In the fixed-interval increment structure, the rate for each income group is increased by a fixed interval compared to the previous income group. In the fixed-percentage increment scheme, each income group experiences a fixed percentage increase in the VMT fee rate compared to those who earn less.

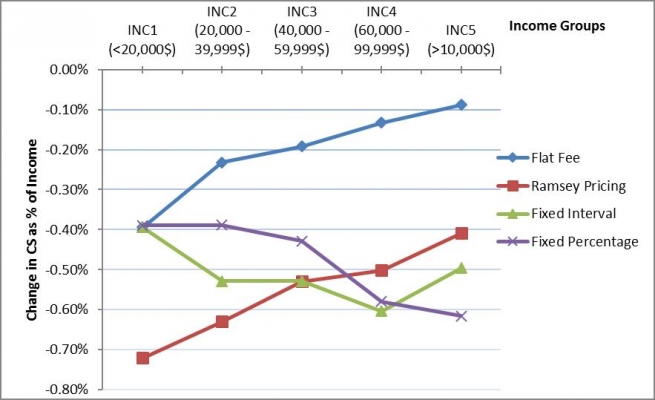

To assess the distributional effects of the proposed variable-rate VMT fees, we modelled the implementation of all policy schemes using a statewide transportation travel demand model for Maryland, and then evaluated them based on the change in consumer surplus (CS) as a percentage of income. Figure 1 confirms previous research findings, i.e. that a flat-rate VMT fee is regressive across all income groups. The Ramsey pricing policy, which reflects the market price and demand elasticity, is slightly less regressive than the flat-VMT fee policy but still imposes a heavier burden on lower-income groups. The fixed percentage policy is progressive across all income groups, but tends to punish people in higher income groups. Only the fixed interval incremental policy performs in a “fair” way overall and can be viewed as progressive.

Figure 1 – Distributional Impacts by Income Group

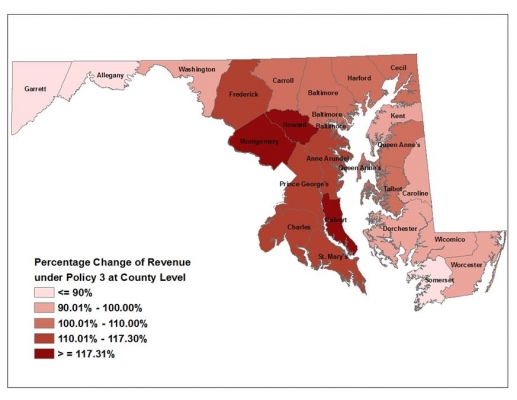

Employing a travel demand model for policy analysis allows us to obtain and visualize the results in more detail. With additional information, such as the spatial distribution of revenue change or VMT change, analysts and decision-makers can better evaluate different policies and make well-informed decisions. Figure 2 illustrates how each county will be affected under the Fixed Interval scheme: Montgomery, Howard, and Calvert counties will contribute the most to the additional revenue generated. These three counties are top-ranked in the per-capita income list for Maryland. Counties with a lower per-capita income, like Somerset, Allegany, and Garrett counties, contribute less in the additional revenue generated.

Figure 2 – Percentage Changes of Revenue in Maryland at the County Level

Results show that when the VMT fee rate increases pro rata with users’ income, variable-rate fee structures do not have a significant impact on their travel behavior, compared to the flat VMT fee. On the revenue generation side, VMT fee policies can supplement the existing fuel tax revenues to mitigate the fiscal deficit. The three income-based VMT fees are all designed to double the revenue generated so that they are comparable with respect to their impacts on consumer surplus and travel behavior. Among the proposed fee structures, the policy with a fixed interval increase rate as people’s level of income improves is considered to be progressive overall. Developing alternative transportation funding strategies to replace the current fuel taxes is a complex task that must account for many issues. While we discuss equity in our work, other policy design criteria should also include practicality, simplicity, revenue generation, and a consideration of the design’s impact on surrounding jurisdictions.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Equitable and progressive distance-based user charges design and evaluation of income-based mileage fees in Maryland’, in Transport Policy.

Featured image credit: Greg Wass (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2epNFpI

______________________

Di Yang – University of Maryland

Di Yang – University of Maryland

Di Yang is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the University of Maryland, College Park. His research interest includes transportation policy analysis using statistical models and large-scale travel demand models. His dissertation research focuses on applying grammar theory in modeling sequential behaviors in transportation.

Eirini Kastrouni – University of Maryland

Eirini Kastrouni – University of Maryland

Eirini Kastrouni is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Transportation Engineering Program at the University of Maryland. Ms. Kastrouni’s research experience lies in the area of transportation economics, in terms of alternative funding policies, investment scenarios, project evaluation and equitable redistribution mechanisms. Ms. Kastrouni has published her research work in renowned transportation journals and has presented in numerous conferences both in the U.S. and internationally.

Lei Zhang – University of Maryland

Lei Zhang – University of Maryland

Lei Zhang is Herbert Rabin Distinguished Professor in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Director of the National Transportation Center at the University of Maryland – College Park (UMD). Dr. Zhang has published more than 200 peer-reviewed journal and conference papers on topics including large-scale transportation systems modeling and simulation, travel behavior, network dynamics, transportation economics and policy, and innovative mobility and sustainability solutions.

The statements in the first paragraph render this whole study invalid…if in fact the presumption that the countries roads are underfunded.

If they were truely researchers, they would have known that the gas tax provides more than sufficient funds to fix the nations roads. But in the 1990s congress chose to raid the cookie jar and redirect funds to other issues.

Second, making a value judgement in a supposedly scientific study impeaches the study. Who are they to determine that sin taxes for making a comfortable living is fair?

A vehicle Mile Tax would will never be accepted by the american public. I refer to this as “Track and Tax” because it requires monitoring every person everywhere they drive — What you call the “Travel Demand Model” would require this. Just the civil liberties implications of such a proposal are ghastly. Such a tax is also far more inefficient than collecting gas taxes, for which a very simple and efficient collection mechanism already exists..

These taxes would unquestionably be higher than the gas taxes Marylanders already pay — even though the state legislature just passed a huge gas tax hike which automatically increases every year. What did they do with the money they took from motorists last year?

Any such proposal would face unrelenting opposition from motorists. I would suggest that new motorist organizations might form for the sole purpose of opposing such a tax. The fact that Anthony Brown’s name appeared on a previous VMT tax proposal is one of the reasons he was defeated in the last election. The mere possibility that such a thing could be contemplated under his administration was enough to bring voters out against a democrat in a deep blue state. At a national rather than state level, such a tax would be a total non starter. You would have to win the support from lawmakers from rural states Montana and Wyoming where people need to drive VAST distances in day to day life. Taking the bus is not an option in those areas.

Driving is critical to the economy of Maryland and the Nation. This is not a “sin tax” it is a tax on working people. In order to collect the revenue you seek, you would NEED to tax the working class, the “one percent” doesn’t do such a disproportionate amount of driving that just taxing them would collect the revenue you are seeking.