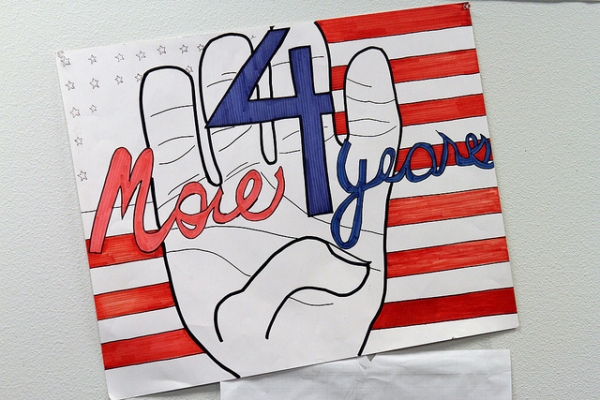

Donald Trump is the new President of the United States. But should the 45th president expect to gain another four years in the White House? Looking at presidential elections over the past six decades, Ben Worthy argues that incumbency is a distinct advantage to presidential candidates, meaning that presidents are more likely to stay in the White House than to go.

Donald Trump is the new President of the United States. But should the 45th president expect to gain another four years in the White House? Looking at presidential elections over the past six decades, Ben Worthy argues that incumbency is a distinct advantage to presidential candidates, meaning that presidents are more likely to stay in the White House than to go.

Donald Trump has been elected President of the United States and will soon inhabit the office of Abraham Lincoln and FDR. For those deeply concerned by his win, myself included, one question (and hope) is whether he will be a one term leader and be gone in 2020, in the next presidential election 1,455 days from now.

Whatever they claim, all conventional political leaders think about re-election constantly. When Trump enters the White House in January 2017 he should be instantly be thinking about winning again in 2020. ‘Every day’, as Barack Obama said, ‘is election day’. But what are the chances of 45 (as he’ll be known) being thrown out or re-elected in four years?

Table 1 – Post War Presidents and Their Second Terms

| President | Did They Win A Second Term? | Why No Second Term? |

|---|---|---|

| Harry S. Truman | No | Voluntarily stepped down/did not run |

| Dwight Eisenhower | Yes | |

| John F. Kennedy | No | Assassinated |

| Lyndon Baines Johnson | No | Voluntarily stepped down/did not run |

| Richard Nixon | Yes | |

| Gerald Ford | No | Lost |

| Jimmy Carter | No | Lost |

| Ronald Reagan | Yes | |

| George Bush | No | Lost |

| Bill Clinton | Yes | |

| George W Bush | Yes | |

| Barack Obama | Yes | |

Looking at this table of all the presidents since the Twenty-Second Amendment of 1947 (the constitutional change that placed a two term limit on incumbents) six presidents were re-elected and six were not. It appears that there are exactly equal chances, a 50/50 possibility, of President Trump winning again or losing office in 2020.

So is there really an equal chance of Trump staying or going? Digging into the details, it’s a little more complex and uncertain. Three presidents outright lost their re-election bids: Gerald Ford in 1976, Jimmy Carter in 1980 and George Bush Snr in 1992. All seemed to have been terminally disrupted in one way or another and were felled by, respectively, a better opponent, an October surprise and their lack of the ‘vision thing’.

Not all of those who didn’t get a second term were defeated in elections. John F. Kennedy never ran for re-election because he was assassinated. It’s not clear if Kennedy would have won in 1964 but, against Barry Goldwater, it would have been very likely. Meanwhile Harry Truman in 1952 and LBJ in 1968 opted not to run, having been essentially defeated in advance by their own unpopularity. Although it is almost certain both would have lost if they ran, LBJ’s Vice President came within an ace of beating Nixon in 1968. In 1976 incumbent Gerald Ford, despite being the second least popular President in history after pardoning Nixon for Watergate, nearly won, losing 48 percent against 50 percent. Nor does winning two terms guarantee greatness – some polls of post-war Presidents give quite a mixed picture.

Cutting the table a different and less reassuring way, winning seems to be the pattern for the holder of the office in the last few decades. Recent history seems to show a stronger incumbency factor – the last three presidents since Bill Clinton all served two terms and, going back to Ronald Reagan, the last four out of five won re-election, with Bush Snr the odd one out in 1992.

Why is there this apparent incumbency advantage or a challenger disadvantage? The incumbent has the experience of running and winning a Presidential campaign. Being in office brings with it various critical resources, from having a proven record, to the ability to get things and guaranteed media attention. Being president should also (normally) mean not having to fight a gruelling, divisive money and energy-sapping primary like your opponent will.

The real danger is the next four years. There are few checks and balances in the US system at present. The legislature is Republican and the Supreme Court has one vacancy and two elderly judges, so there is less hope in the seemingly endless gridlock of US politics. More worrying is that Trump, for all his conciliatory acceptance speech, is no believer in democracy, freedom of speech or individual rights. He has repeatedly undermined the democratic process, praised authoritarian leaders and was, as David Remnick put it, ‘elected, in the main, on a platform of resentment’. As Mark Mazower has pointed out, while this may not be fascism the ‘hollowing out of…basic institutions’ and ‘extremism of political discourse’ that Trump’s victory heralds was certainly the breeding ground for it. The victorious anti-democratic Trump has much opportunity and little to stop him.

That is, of course, unless something blows the Trump presidency off course: a scandal, a crisis or an unexpected obstacle. Such unexpected events have disrupted many presidential careers, having roundly defeated Ford, Carter and Bush and persuaded Truman and Johnson not to run. And American politics today, and the world in 2016, seems to thrive on the unexpected.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Featured image credit: Barack Obama (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2fnZHfh

______________________

Ben Worthy – Birkbeck College

Ben Worthy – Birkbeck College

Ben Worthy is a Lecturer in Politics at Birkbeck College. He is co-editor of the Measuring Leadership Blog.