The Democrats are now locked out of the presidency for at least another four years and the Majority in the US House and Senate until 2018 or even beyond. But, writes Tyler Hughes, they may still be able to influence policy debates in Congress. By studying more than 43,000 House speeches over 23 years, he finds that when a minority party increases attention on an issue, so does the majority party, a tactic which House Democrats may be able to use to influence policy debates.

The Democrats are now locked out of the presidency for at least another four years and the Majority in the US House and Senate until 2018 or even beyond. But, writes Tyler Hughes, they may still be able to influence policy debates in Congress. By studying more than 43,000 House speeches over 23 years, he finds that when a minority party increases attention on an issue, so does the majority party, a tactic which House Democrats may be able to use to influence policy debates.

The majority party dominates nearly every aspect of the legislative process in the US House of Representatives, allowing very little involvement from the minority party in policy decisions. In new research, I reveal how the minority party influences the amount of attention the majority party pays to particular policy issues through the use of legislative speeches. The apparent interplay between the parties during policy debates highlights the mostly unseen ways in which the minority party affects policymaking in the House.

The unique rules of the House of Representatives give the majority party near complete control over the chamber’s legislative outputs. The majority exerts this control over the policymaking process through key positions, such as committee chairs and the Speaker of the House. The House Committee on Rules (controlled by the majority party) also places strict limits on floor debate and amendments before each piece of legislation is sent to the chamber floor. To put these rules in context, the Senate does not place constraints on debate, which allows the minority party to force compromise through the use of filibusters and other delaying tactics. In contrast, the majority party in the House simply uses the institution’s rules to steamroll the minority.

One thing the majority party cannot control is the amount of attention legislators pay to policy problems not considered formally through current legislation. Broad attention to different policy issues is not just some abstract academic notion; it has very real policy implications. Across a number of policymaking institutions and policy issues, political science research clearly demonstrates how dramatic shifts in attention from one issue to another often precipitate significant policy change.

A 2008 debate over the leasing of offshore oil reserves in the Gulf of Mexico provides one such example. Motivated by historically high gas prices, House Republicans—the minority party at the time—began a tirade of floor speeches in favor of expanding US offshore drilling leases. Over the course of the summer, Republicans delivered more than 100 one-minute speeches (a period of debate at the beginning of each legislative day in which members are free to address the chamber, regardless of party or seniority) advocating for increased energy exploration. The tactic worked. Democrats quickly shifted their collective attention to the issue, and eventually ended the 25-year-old moratorium on offshore drilling.

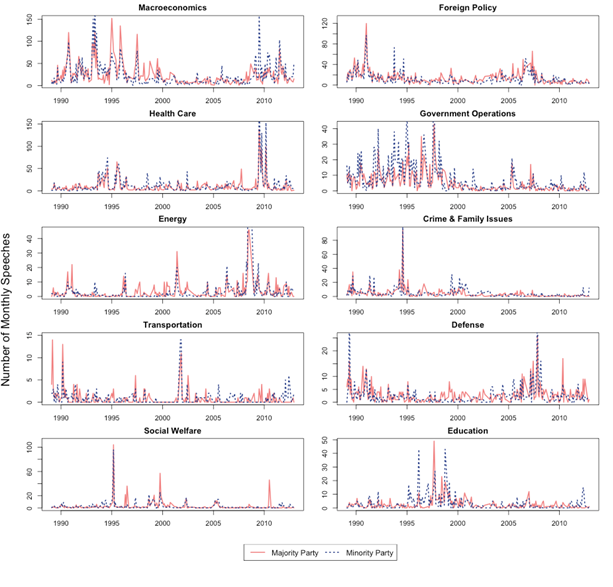

Significant policy change—like the 2008 change to US offshore drilling policy—is rare, but floor speeches offer insight into the ability of parties to influence the broader policy considerations of the chamber. As demonstrated in Figure 1 below, the parties devote significant attention to only a handful of salient issues during floor speeches, but the parties dedicate similar amounts of attention to the same issues over time. There are also clear patterns in the data. For example, there is a huge spike in the number of speeches about health care policy during the 2009 debate over the ACA. You can also see the increased number of speeches on energy policy during the debate over offshore drilling in 2008. The timelines displayed below indicate policy debates are not dominated by one party or the other. Rather, the parties obviously feed off of one another and compete to control the policy debate.

Figure 1 – Monthly Count of One-Minute Speeches, by Party and Policy Topic 1989-2012

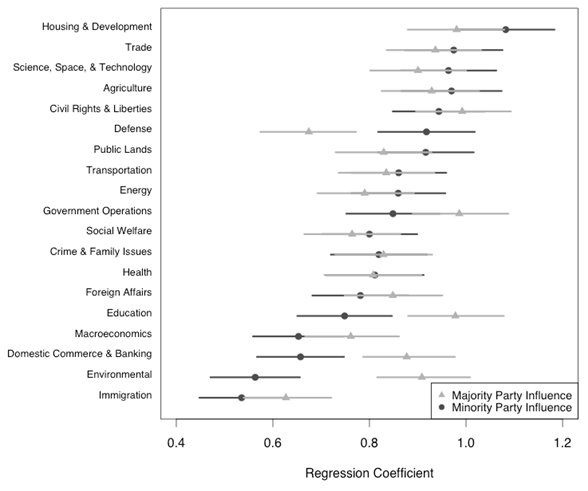

My analysis of more than 43,000 one-minute speeches delivered on the floor of the House between 1989 and 2012 highlights how the minority party affects the majority party’s attention to particular policy issues. When the minority party increases attention to an issue, the majority party responds by also increasing attention to the issue. Figure 2 below shows how the minority party is able to elicit this response from the majority party across a range of issues (larger regression coefficients indicate a larger response). The analysis suggests a shift in minority party attention of one speech on a given policy issue produces a corresponding change of slightly less than one speech from the majority party. Therefore, the minority party may need to deliver a large number of speeches on a particular topic before the majority party gives a noticeable reply.

Figure 2 – Measuring the Amount of Influence Each Party Exerts Over the Other in One-Minute Speeches

My findings also highlight how influence on attention is a two-way street—the majority party also influences the minority party’s levels of attention. On some issues, the effect of minority party influence is larger; on others the effect of the majority party is larger. Regardless, the analysis reveals a clear give-and-take between the parties, which inherently implies influence from the minority party.

The majority party may dominate final legislative action in the House, but it is clear the minority party has at least some impact in deciding which policy problems the chamber addresses. This is especially important considering both chambers of Congress and the presidency will be controlled by Republicans until at least 2018. As the minority party, Democrats will have very few options to exert their political will through the legislative process. The ability to influence the broader policy debate in Congress may prove to be a vital (if largely unseen) tool for the opposition.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Assessing minority party influence on partisan issue attention in the US House of representatives, 1989–2012’, in Party Politics.

Featured image credit: Lawrence Jackson (whitehouse.gov) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2gIHEB3

_________________________________

Tyler Hughes – California State University, Northridge

Tyler Hughes – California State University, Northridge

Tyler Hughes is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at California State University, Northridge.