The incoming Donald Trump administration has sparked a new debate over the value of school vouchers in American education policy. But just how effective are school vouchers? In new research which examines a school voucher program in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Michael R. Ford finds that more than 40 percent of schools which received school voucher revenues now no longer exist. He writes that this high voucher school failure rate is down to the design of the scheme itself. Educational entrepreneurship and school failure, it seems, are two sides of the same coin.

The incoming Donald Trump administration has sparked a new debate over the value of school vouchers in American education policy. But just how effective are school vouchers? In new research which examines a school voucher program in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Michael R. Ford finds that more than 40 percent of schools which received school voucher revenues now no longer exist. He writes that this high voucher school failure rate is down to the design of the scheme itself. Educational entrepreneurship and school failure, it seems, are two sides of the same coin.

President-elect Donald Trump’s campaign promise to spend $20 billion on school choice, as well his choice of school choice supporter Betsy DeVos as Secretary of Education, has brought the issue of school vouchers to the forefront of American education policy. In no American city are the impacts of voucher policy better understood than Milwaukee, Wisconsin, home of the nation’s largest and oldest urban school voucher program. The logistics of the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program (MPCP) are relatively simple. Milwaukee residents with household incomes at or below 300 percent of the federal poverty level are able to direct a voucher (worth $7,323 for K-8 students) to the participating private school of their choice.

What started in 1991 as a small experiment in market-based education now educates almost twenty-five percent of all publicly funded students in the City of Milwaukee. The MPCP, by design, encouraged the creation of new private entrepreneurial schools to compete with the traditional Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS) sector. Indeed, between 1991 and 2015 121 new private schools opened their doors in order to participate in the voucher program. However, as Fredrik Andersson and I detail in new research, 67.8 percent of these start-up schools are no longer in operation. In fact, 41 percent of all private schools that ever received voucher revenues no longer exist.

Why is the voucher school failure rate in Milwaukee so high? Why does it matter? And what can the Milwaukee experience teach policymakers considering new school voucher programs?

The failure rate is high due to both the very nature of voucher school policy, as well as the specific design of the MPCP. In 1955 economist Milton Friedman proposed school vouchers as a means of injecting market competition into a monopolized government school sector that had grown indifferent to parental and student needs. Friedman’s vision included the creation of new entrepreneurial schools. Under basic market theory organizations that are unable to compete eventually go out of business. In retrospect, it should not be terribly surprising that so many schools would fail in a robust educational marketplace. However, the specific design of the MPCP exacerbated the failure rate.

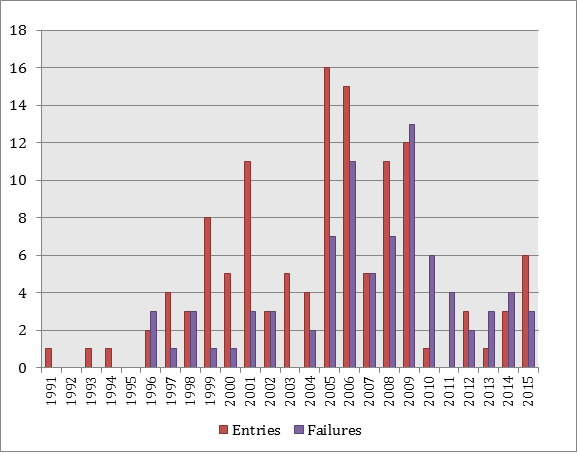

For much of the program’s history it was remarkably easy to open a new school. If an entrepreneur had a building, filed a one-page form with the state, and was able to attract Milwaukee students who met the program’s income eligibility requirements, the school was eligible to receive government funds. Basic regulations requiring school accreditation, the presence of a curriculum, and degreed teachers, were not implemented until the mid and late 2000s. The uptick in regulation was a response to concerns about accountability for both performance, and the increasing public investment in the voucher school sector. However, the new regulations also increased the school failure rate. As can be seen in Figure 1 below, the numbers of failures increased from 2005, in part because of the ability for the state to cut off funding to schools that failed to meet new program requirements.

Figure 1 – Start-Up School Entries and Failures

Certain organizational and program characteristics affect a schools failure risk. First, start-up schools are four times as likely to fail as schools that existed prior to participating in the voucher program. These schools also tend to fail within their first few years of operation, and only after ten years does their failure risk mirror that of the previously existing schools. Second, religious schools have a much lower failure risk, likely due to the resources provided by their affiliation with an umbrella organization like the Catholic Archdiocese. Third, failure rates are, not surprisingly, a function of the program’s overall level of regulation. When the state requires more of voucher schools, fewer survive.

It is of course possible to argue that the failure of low-quality MPCP schools is a positive. In an education marketplace schools that cannot attract enough parents or meet basic state regulations should go out of business. However, the actions of Wisconsin policymakers, including the implementation of barriers to entry for new schools and tougher standards for existing schools, reflect a desire to prevent school failures. The public investment in failed MPCP schools, estimated at almost $200 million, also calls into the question the overall taxpayer savings attributable to school voucher programs. Arguably most problematic is the disruption in students’ lives and educations when a school suddenly closes.

So what are the lessons from the Milwaukee voucher experience? First, school choice programs designed to encourage entrepreneurship will also result in school failures. Policymakers should expect schools to close, and make certain that the impacts of school failure are considered during political debates over voucher policy. Processes for orderly school closures, including provisions for the transfer of student records and materials, should be developed in order to minimize the disruption to students who attended failed schools, and the schools who that must enroll these students moving forward.

Second, policymakers can reduce failure risk by requiring that schools be in existence for a number of years prior to receiving vouchers, and/or requiring that schools be affiliated with a larger umbrella organization as a condition of participation. Both of these requirements, however, represent a trade-off between the benefits of entrepreneurially driven innovation and failure risk. Milwaukee demonstrates that educational entrepreneurship and school failure are two sides of the same coin.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Determinants of Organizational Failure in the Milwaukee School Voucher Program’, in the Policy Studies Journal.

Featured image credit: Phil Roeder (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2hPQfBx

_________________________________

Michael R. Ford – University of Wisconsin–Oshkosh

Michael R. Ford – University of Wisconsin–Oshkosh

Michael R. Ford is assistant professor of public administration at the University of Wisconsin–Oshkosh. His research interests include public and nonprofit board governance, accountability, and school choice. He is a member of the Thomas B. Fordham and American Enterprise Institutes’ Emerging Education Policy Scholars class of 2015–16, and a 2016 ASPA Founders Fellow. Prior to joining academia Michael worked for many years on education policy in Wisconsin.

Ford provided a good account of how increasing government regulation of private education providers eventually supplanted parents’ ability to hold schools accountable, causing parent-favoured schools to close due to onerous regulations. Clearly, increasingly onerous government regulations helped many private schools to fail. Parents’ voucher votes were ignored.