It is an understatement to state that Donald Trump’s victory took Democrats and many commentators by surprise. Rakib Ehsan takes a close look at just how Hillary Clinton lost the election, from Trump’s dominance among white voters, to his higher than expected support among Hispanics, and the enthusiasm gap between Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton. In order to regain the White House, he writes, Democrats will have to create a more sophisticated on-the-ground electoral strategy across all states and work better within the mechanics of the Electoral College system.

It is an understatement to state that Donald Trump’s victory took Democrats and many commentators by surprise. Rakib Ehsan takes a close look at just how Hillary Clinton lost the election, from Trump’s dominance among white voters, to his higher than expected support among Hispanics, and the enthusiasm gap between Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton. In order to regain the White House, he writes, Democrats will have to create a more sophisticated on-the-ground electoral strategy across all states and work better within the mechanics of the Electoral College system.

November 8th 2016 marked one of the greatest upsets in modern Western electoral history, with Donald Trump defeating Hillary Clinton in the race for the White House. The result left many political analysts, the mainstream media, countless pollsters and numerous bookmakers in shock – how had they got it so wrong? While Clinton won the popular vote by a considerable margin (which has reignited the debate over the democratic nature of the Electoral College Vote system), there are a number of identifiable reasons rooted in demography and geography which can explain for Trump’s surprise victory.

Based on the National Election Pool exit poll conducted by Edison Research consisting of over 24,000 respondents, we can clearly pinpoint where the election was won and lost – where the expectations held by the Clinton campaign were not met and where Trump performed better than what was generally predicted. There were challenges facing Clinton leading up to the election – the inherent appetite for change after two terms of Democratic control of the White House, being presented as a ‘political insider’ amidst a wave of anti-establishment sentiment, and the task of reassembling Obama’s broad-based electoral coalition of young, minority and college-educated voters.

Trump’s dominance among white voters

Trump’s overwhelming support among white voters comfortably overcame any electoral advantage Clinton held among minority voters – which itself had weakened from 2012. Despite 2016 being the most diverse electorate in US Presidential Election history, 70 percent of the electorate was white, who voted in favour of Trump by a margin of 58 percent to 37 percent. Among men, there was a 32 percentage-point differential between the two candidates (Trump 63 percent / Clinton 31 percent), while for white women, this narrows down to a 10 percentage-point gap in favour of Trump (53 percent / 43 percent). This demonstrates the importance of the ‘white male’ vote in Trump’s victory, with the data from the Rust Belt states which turned from blue to red reinforcing this point.

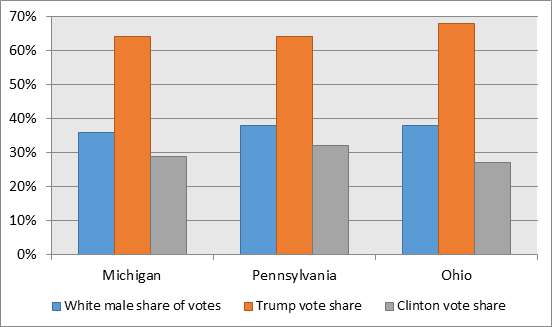

While 34 percent of the votes in the election were white men, this percentage was higher for states located in the industrial Midwest (as Figure 1 shows) – and often equalled or exceeded the nationwide 32 percentage-point difference between the two candidates.

Figure 1 – White male share of votes and candidate vote share in the Midwest

While the percentage-point difference within this specific demographic was only 24 points in favour of Trump in Wisconsin, white men formed 42 percent of the state’s votes. In these overwhelmingly white state electorates, Trump’s overwhelming popularity with white men (specifically non-college-educated) played a crucial part in breaching Clinton’s Midwest blue firewall.

While young and college-educated voters were critical components of the ‘Clinton coalition’, within the white vote the Democratic candidate fell considerably short of expectations. Among white voters aged 18-29, Trump defeated Clinton by a 5 percentage-point margin (48 percent / 43 percent). While this is technically an improvement in terms of percentage-point difference from the 2012 Election, where Romney beat Obama by 51 percent to 44 percent, the Democratic share of the vote dropped. While Clinton won the overall 18-29 age group by 55 percent to 37 percent (boosted by minority millennials), the Democratic share of the vote fell by 5 percentage points from when Obama beat Romney by 60 percent to 37 percent. Clinton’s popularity among young voters did not come close to reaching the heights of nationwide millennial excitement generated by Obama.

Where Clinton was expected to do exceptionally well was among white college-educated women – particularly those who would usually be inclined to vote Republican. Despite the ‘Access Hollywood’ audioclip scandal, along with making a number of other remarks during his Presidential campaign which were widely considered to be misogynistic and sexist and Clinton’s natural appeal to more-educated voters, Trump only lost to the Democratic nominee by just 6 percentage points (51 percent / 45 percent).

Trump’s proclamation that he ‘loves the poorly-educated’ was very much reflected in the white vote. Nearly 3 in 4 white non-college-educated men (72 percent) chose Trump over Clinton, who won less than a quarter of votes within this demographic (23 percent). Among non-college-educated white women, Trump held a 28 percentage-point difference (62 percent by 34 percent). With white college-educated voters forming 37 percent of the electorate and white voters without a college degree representing 34 percent of votes cast, Clinton’s under-performance among more-educated white voters and Trump’s barnstorming effort among less-educated voters living in rural areas provided him with a strong base for victory in the election.

Trump’s higher-than-expected support among Hispanics

What this election proved in the strongest terms was the mistake of treating the US Hispanic population as a monolithic, one-dimensional, single-issue voting bloc. Trump’s inflammatory comments towards undocumented Mexican migrants, questioning the integrity of a federal judge presiding in the Trump University case on the grounds of his Mexican ancestry, and labelling former Miss Universe Alicia Machado as ‘Miss Housekeeping’ led some to believe that the now President was on the verge of suffering a ‘Hispanic catastrophe’ at the ballot box. However, Trump’s performance among Hispanic voters was anything but a disaster.

The diversity in vote choice among the US Hispanic ‘community’ was demonstrated in no stronger terms than in the key battleground state of Florida. In the Sunshine State, voters of Cuban heritage were about twice as likely to vote for Trump in comparison to non-Cuban Latino voters. This was potentially an expression of discontent among established Cuban-American voters who are uncomfortable with the speed of normalisation regarding US-Cuba relations. While 54 percent of Cuban-heritage voters provided their electoral support for the Republican President, just over a quarter of non-Cuban Latinos (26 percent) followed suit. While over 4 in 10 Cuban-heritage voters voted for Clinton (41 percent), 71 percent of non-Cuban Latino voters opted for the Democratic nominee. This would have been largely driven by Democratic support among Puerto Rican voters – many of whom have recently fled the island’s economic crisis.

The mistake made by Clinton campaign strategists, political pundits and the mainstream media was to assume that Donald Trump’s hardline stance on border security, immigration and deportation would lead to overwhelming ‘Hispanic support’ for the Democrats. Clinton did win battleground states with noticeably high Hispanic populations, such as Colorado and Nevada. However, the 44 percentage-point advantage Obama had over Romney in 2012 (71 percent to 27 percent) was narrowed to 36 percentage points in this election.

Obama-Clinton Enthusiasm Gap

The ‘Obama-Clinton’ enthusiasm gap among black voters in this Presidential election also hurt the Democrats. Black voter representation in the electorate dropped from 13 percent to 12 percent and the Democrat-Republican percentage-point difference dropped from 86 to 80 points. What is interesting to see is the downturn in Democrat votes in areas heavily populated by black voters in a number of states.

In Wayne County, Michigan which includes Detroit, the Democratic vote dropped by 77,806 votes from the 2012 Election, while Trump increased Romney’s total by 14,378 – so these ‘missing Obama voters’ could have helped the Democrats maintain Michigan (which is as of yet undeclared due to the razor-thin difference in the vote count). In Wisconsin, Trump defeated Clinton by 27,389 votes. In Milwaukee County, the Democratic vote dropped 39,104 votes – and interestingly, the Republican vote had decreased by just over 32,000 votes. Had Clinton simply managed to win the same number of votes as Obama in 2012 in this county, Wisconsin would have also remained Democrat. This would have secured 26 Electoral College votes across the two states.

A drop in urban turnout assisted Trump in carrying Pennsylvania. While a single county in the Keystone State wouldn’t shift the outcome as it could in the previously stated cases, it is important to recognise that the Democratic vote in Philadelphia County dropped by 25,581 votes from 2012 – roughly 40 percent of Clinton’s state-wide deficit. What these three particular counties have in common is that they are all heavily populated by African-American voters. The ‘Obama-Clinton’ enthusiasm gap was reflected in other key battleground states. In North Carolina, the black share of the electorate dropped from 23 percent in 2012 to 20 percent, with Democratic support decreasing from 96 percent to 89 percent. While in Florida the share of black voters rose from 13 percent to 14 percent, Democratic support among this demographic of voters fell by 11 percentage points.

This could be explained by a number of factors. The fact Obama was not on the ticket may have reduced the degree of enthusiasm among some black voters to participate in the election and to turn out in key counties within important swing states. There were issues surrounding photo identification voting laws which are often reported to disenfranchise lower income, urban and minority voters, along with the availability of polling stations in predominantly black areas – particularly in North Carolina. However, what the Democrat and Republican shifts in the share of the black vote in comparison to 2012 do show is that Clinton’s reliance on an ‘anti-Trump’ method of campaigning had its limitations in terms of effectively engaging with African-American voters.

Where to next for the Democratic Party?

There are many reasons which can explain for the result of the 2016 Presidential Election. What is clear from the survey data from the exit poll was that it was anti-establishment sentiment in predominantly white communities – particularly those in the rust belt and other key states such as Florida and North Carolina – which handed Trump the keys to the White House. Despite the 2016 electorate being the most diverse in US Presidential Election history, it was not the speculated strength of anti-Trump sentiment within US ethnic minorities which decided this election.

The blue-to-red switch among the Democratic Party’s traditional core vote in the Rust Belt poses a number of challenges for the party. How does it approach the issue of trade? Trump’s relentless criticism of transnational trade agreements such as NAFTA and the Trans-Pacific Partnership and protectionist threats towards countries such as China went down particularly well in the industrial Midwest. Similar to a number of progressive parties of the left in Europe, the Democrats seem to be experiencing a fundamental weakening in its relationship with its traditional blue-collar supporters who have struggled under the market forces of globalization.

The party must also create a more sophisticated on-the-ground electoral strategy across all states – the potentially devastating loss of black voters in Wayne County, Michigan and Milwaukee County, Wisconsin (a state Clinton did not visit once as Democratic presidential nominee) show the limitations of her campaign. This was perhaps a case of sheer complacency – but such mistakes are unforgivable in the context of the US Presidential Election. The over-dependence on anti-Trump campaigning to galvanise African-American voters is something to be learnt from this election.

The ‘Hispanic’ vote which was widely reported to be the section of the US electorate which would bring Trump’s downfall exposed itself to be one which is diverse, multi-dimensional and heterogeneous in terms of policy interests and concerns. Based on survey data on social attitudes towards immigration, deportation and border security, it is clear that Trump’s hardline agenda incorporating these issues would have resonated with a substantial proportion of Latino voters. Trump may even feel further emboldened to pursue his hardline agenda on border security in light of his higher-than-expected support among US Hispanic voters.

Clinton’s failures among traditional white working-class voters in the Midwest, college-educated white voters, African-Americans and Latinos show that she was simply unable to galvanise her targeted coalition. While this should not wholly detract from the fact that she won the popular vote by more than 2.5 million votes, the Democrats must better work with the mechanics of the Electoral College Voting system in the future and understand both the demographics and specific policy concerns in certain regions, states and counties.

In an election where both main presidential candidates were deeply unpopular, primarily relying upon anti-Trump sentiment was always a risk-laden strategy. How the Democrats, who are now faced with a Donald Trump presidency and Republican majorities in both houses of the US Congress, respond to this shock loss, remains to be seen.

However, it is important to acknowledge that this election also showed that the relationship between the Republican Party and many US ethnic minority voters remain significantly strained. How President Trump conducted his presidential campaign and chooses to manage community relations and address racial inequality issues during his presidency could yet have long-term electoral implications for the GOP as the face of America continues to change.

Featured image credit: Chris Goldberg (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2kk1Iid

______________________

Rakib Ehsan – Royal Holloway, University of London

Rakib Ehsan – Royal Holloway, University of London

Rakib Ehsan is a Doctoral Researcher at Royal Holloway, University of London, specialising in ethnic minority socio-political attitudes and behaviour in the UK. His PhD investigates the various inter-relationships between the ethnic composition of social networks, patterns of interethnic experiences, political-institutional and generalised social trust, and personal self-identification in regards to ethnicity, religion and nationality. He has had work published by Canadian independent think-tank MacKenzie Institute, British think-tank Bright Blue, and The Conversation. General research interests include ethnic minority voting behaviour and the social, economic, and political impact of racial discrimination.

The National Popular Vote bill is 61% of the way to guaranteeing the majority of Electoral College votes and the presidency in 2020 to the candidate who receives the most popular votes in the country, by changing state winner-take-all laws (not mentioned in the U.S. Constitution, but later enacted by 48 states), without changing anything in the Constitution, using the built-in method that the Constitution provides for states to make changes.

All voters would be valued equally in presidential elections, no matter where they live.