In late January, President Trump stated that he would be pushing for new “one-on-one” trade deals with specific countries to replace multilateral agreements; exploiting US economic clout to negotiate deals which benefit the US the most. Markus Gastinger has created an index of trade and economic power in order to determine which countries Trump might try to target. He finds that countries and blocs with which the US has a large trade deficit, such as China and the European Union are too powerful to make good targets. On the other hand, less powerful countries, such as Vietnam and Japan could simply refuse to negotiate. Either way, Trump’s trade policy may well end up being a continuation of the status quo.

In late January, President Trump stated that he would be pushing for new “one-on-one” trade deals with specific countries to replace multilateral agreements; exploiting US economic clout to negotiate deals which benefit the US the most. Markus Gastinger has created an index of trade and economic power in order to determine which countries Trump might try to target. He finds that countries and blocs with which the US has a large trade deficit, such as China and the European Union are too powerful to make good targets. On the other hand, less powerful countries, such as Vietnam and Japan could simply refuse to negotiate. Either way, Trump’s trade policy may well end up being a continuation of the status quo.

One of the best predictors of future behavior is past behavior. The same has been true, in sufficiently broad terms, for US foreign policy since World War II. But President Trump is trying to break with this tradition, as with many others. To learn more about his trade policy, I have turned to his words. While political rhetoric can be an imperfect proxy for future government action, Mr. Trump’s words seem quite close to his true intentions as the erection of a wall – literally, not figuratively – along the border with Mexico illustrates. The focal point for my analysis are his remarks at the Republican retreat in Philadelphia of January 26, which give us better insight into his future trade strategy than the policy statement on the White House homepage, his joint address to Congress or even the President’s Trade Policy Agenda 2017.

We have also withdrawn from the Transpacific Partnership, paving the way for new one-on-one trade deals that protect and defend the American worker and we will have a lot of trade deals … But they will be one-on-one. They will not be whole big mashed pot. They will be one-on-one deals. If that particular country does not treat us fairly, we send them a 30-day notice of termination and they will come and say please do not do that and we will negotiate a better deal. Source

Let us first focus on President Trump’s claim that the US can send 30-day termination notices to ratchet up pressure on other states. Obviously, this refers only to existing Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). The US has fourteen FTAs with twenty countries. In thirteen cases, the notice of termination becomes effective after 180 days (Bahrain, Chile, Korea, Morocco, Oman and Panama) or six months (Australia, Colombia, DR-CAFTA, Jordan, NAFTA, Peru and Singapore). In the case of Israel, the period is even longer (12 months). While Mr. Trump might have gotten the timeframe wrong, the general argument that he can place pressure on countries with which the US has concluded FTAs is not implausible as it would radically alter their Best Alternative to Negotiated Agreement (BATNA). But it would also increase pressure on Mr. Trump to strike a follow-up deal to protect American exports to these countries.

Furthermore, Mr. Trump’s reference to the “American worker” and, more generally, his impassioned rhetoric about the plight of the American manufacturing industry shows that his primary concern will be with trade in goods. This deficit typically reduces when accounting for trade in services, as the Congressional Research Service (pp. 4–5) points out. But when focusing on merchandise trade exclusively, which countries will Mr. Trump target? To answer this question, we also need to factor in the other country’s power. President Trump clearly hopes to exploit power differentials by negotiating bilateral trade deals “one-on-one” (repeated three times in a quote the length of about three tweets).

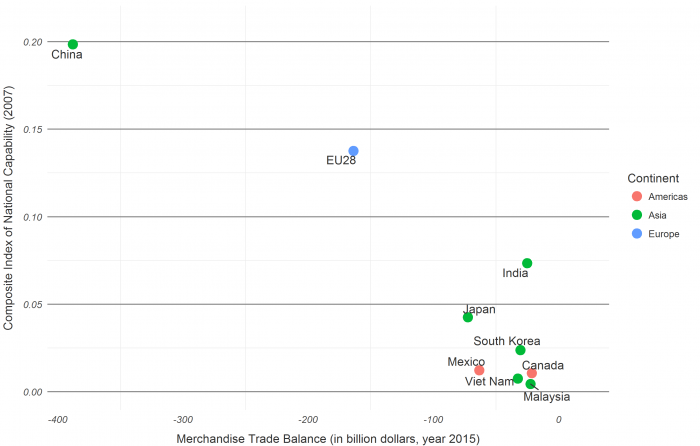

To measure the merchandise trade deficit, I use import and export data from the United Nations Comtrade database. We can account for power through the Composite Index of National Capability (CINC) of the Correlates of War Project, which uses demographic, economic and military indicators to measure power. While the CINC is far from a perfect measure for power, it provides us with a useful metric to plot differences between countries. The lower the CINC for a country, the higher the chances the US will get a “fair” deal.

Figure 1 – Power and the American Merchandise Trade Deficit

Sources: UN Comtrade; Correlates of War Project; own calculations and illustration.

President Trump’s dilemma comes out clearly in Figure 1. Ideally, he would need a country in the lower-left quarter where the merchandise trade deficit is high but power low. But there is no country even close to that area. China individually contributes almost half of America’s trade deficit, but it is by no account a weak country and even tops the power index. The next best target would be the European Union (EU), which accounts for twenty percent of the US trade deficit. Apparently, the EU is one of the “big mashed pots” President Trump would prefer to do away with. Even though Trump wanted to negotiate with EU member states bilaterally, negotiating one-on-one trade deals in the EU is impossible since trade is an exclusive EU competence. Collectively, the EU is too powerful to make a good target. For power considerations, India should also not make it on Mr. Trump’s shortlist.

This leaves less powerful countries in the bottom-right corner. Individually they contribute little to the American trade deficit but taken together they account for over one quarter of it. Given the ability to turn up pressure by sending out written notices of termination, South Korea is a most likely target for the reorientation of US trade. Interestingly, it has not yet been singled out by President Trump. Mexico’s fate is tied to Canada and if the US leaves NAFTA, it would stay behind with Canada. Since Mr. Trump could only give up free trade with Mexico and Canada, he is unlikely to withdraw but will probably renegotiate NAFTA in the shadow of this threat.

Japan, Vietnam and Malaysia would make relatively decent targets, too. However, Trump’s dilemma with states that have no FTA is that they can always choose to keep the status quo and refuse to negotiate, especially if they expect future administrations to show a greater appreciation for their own domestic concerns. Mr. Trump can try to manipulate their BATNA by changing the status quo and attempts to introduce a “border adjustment tax” are best viewed from this perspective. At any rate, any country’s best course of action is to accept starting negotiations with the US but to strike a deal only if it is in their national self-interest. If they do not find sufficient common ground with Mr. Trump’s trade negotiators, they will have at least run down the clock on his administration. Furthermore, by promising to “have a lot of trade deals” (see quote) Mr. Trump even weakens his hand and he may have to conclude deals to meet public expectations rather than substantive demands.

Finally, it is far from certain that this more conflictual approach will pay off and other countries will bow to threats. For example, Mr. Trump’s plans to build a wall and force Mexico to pay for it may make, strictly speaking, economic sense to keep the US in NAFTA, but it has achieved the opposite by galvanizing public opposition to Trump in Mexico. There are numerous examples of how much hardship – even draconic sanctions – states can endure if only they consider themselves on the right side of an argument. President Trump’s trade policy might thus prove more traditional than anticipated and withdrawing from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) may remain his sole signature policy to prove to his supporters that his trade agenda differs radically from that of his predecessors.

Image credit: Human rights trump trade deals by Alisdare Hickson is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2m2dH1n

_________________________________

Markus Gastinger – Technische Universität Dresden, Germany

Markus Gastinger – Technische Universität Dresden, Germany

Markus Gastinger holds a PhD from the European University Institute and is currently research associate at the Chair of International Politics of the Technische Universität Dresden, Germany. His research interests include bilateral trade agreements and international negotiations. He has recently published in the Journal of European Public Policy on the negotiation of bilateral trade agreements in the European Union and in European Political Science on negotiation simulations in higher education teaching. To learn more about him, please visit http://markus-gastinger.eu/ or follow him on Twitter (@MarkusGastinger).