Fact-checking of political events has become an important component of 21st century political campaigns. But does fact-checking actually influence how people vote? In new research, Amanda Wintersieck finds that voters’ evaluations of a candidate’s debate performance – and the chances that they will vote for them – are improved when fact-checks confirm they are making accurate statements. “Half-true” fact check ratings, on the other hand, had no impact on voters’ support for candidates.

Fact-checking of political events has become an important component of 21st century political campaigns. But does fact-checking actually influence how people vote? In new research, Amanda Wintersieck finds that voters’ evaluations of a candidate’s debate performance – and the chances that they will vote for them – are improved when fact-checks confirm they are making accurate statements. “Half-true” fact check ratings, on the other hand, had no impact on voters’ support for candidates.

Political debates are an important part of modern campaigning. These events allow candidates to make their case to a large viewing audience, and to persuade voters to support their candidacy. Today, political debates are often pored over by fact-checkers in real time. Fact-checking organizations, such as FactCheck.org and PolitiFact, as well as more traditional journalist fact-checkers like the New York Times, offer citizens assessments of the accuracy of a candidate’s statements within moments of those statements being made. Despite the rise of fact-checking in recent elections, we know very little about how fact-check messages and source cues impact voters’ assessments of political candidates.

I conducted an experiment utilizing one political debate from the 2013 New Jersey Gubernatorial race between Chris Christie and Barbara Buono in combination with fact-checks that offer either confirming information (a fact-check that states the information in the debate message is accurate), corrective information (a fact-check that states the information in a debate message is inaccurate), or a mix of confirming and corrective information. In addition, the fact-checks source varied (FOX, MSNBC, PolitiFact). Three hundred twenty-one subjects participated in the experiment.

In each condition, participants were first exposed to an edited version of one of the 2013 New Jersey gubernatorial debates. The edited version included both candidates’ opening and closing statements and three issue areas. In nine of the conditions, a fact-check was added as a banner at the bottom of the screen.

The results from my experiment show that fact-check messages influence citizens’ evaluations of candidates and their vote intentions. Specifically, in conditions where the fact-check indicates that a candidate is being honest, people’s evaluations of the candidate’s debate performance are improved. Respondents are also more likely to indicate that the candidate won the debate. However, these evaluations flip when the fact-check indicates that the candidate is lying. Respondents were less likely to say the candidate won the debate and gave lower performance evaluations in these conditions.

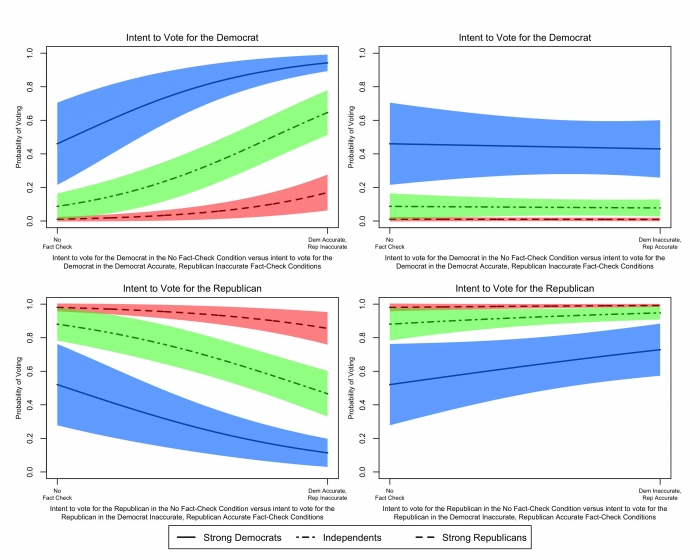

While partisans were more likely to indicate their intent to vote for the political candidate of their preferred party, this intent was affected by exposure to the fact-check. As Figure 1 shows, strong Democrats were 47 percent more likely to vote for the Democrat in the race when they were exposed to a fact-check highlighting the candidate’s honesty. Independents and strong Republicans were 54 percent and 16 percent, respectively, more likely to vote for the Democratic candidate. Additionally, strong Republicans, Independents, and strong Democrats were 12 percent, 40 percent, and 40 percent, respectively, less likely to indicate a willingness to vote for the Republican candidate in experimental conditions where the Republican candidates’ statements were described as mostly false.

When the Democratic candidate’s statements were described as mostly false, Independents and strong Democrats were 7 percent and 20 percent more likely to indicate that they would vote for the Republican candidate in the race.

Figure 1 – How exposure to a fact-check message influences partisan’s intentions to vote

However, the results from mixed accuracy fact-check conditions are much more similar to the no fact-check condition. That is, half true fact-check ratings do not improve assessments of the candidate’s debate performance, evaluations of the debate winner, or intentions to vote for either candidate. Receiving a half true fact-check is the same as receiving no fact-check at all. This observation calls into question the usefulness of the “half true” fact-check ratings that are so popular with major fact-checking outlets like PolitiFact. Additionally, I found no evidence that the source of a fact-check (PolitiFact, FOX, or MSNBC) influenced a citizen’s opinion of political candidates.

My results suggest that fact-checking has the power to move assessments of candidates by providing instant analysis of candidates’ political statements. Fact-checking in this new form of instant media analysis is growing, with most major political events being fact-checked as they progress. Just a decade ago, we were able to gauge citizens’ opinions of political events pre and post media analysis, however, with the instant fact-checking of today, it will become increasingly difficult to separate citizens’ attitudes without the media’s influence.

That fact-checking, regardless of source, has the power to move assessments of candidates for political office may be of some concern in light of the new fact-checking that emerged in the 2016 election. During the course of the 2016 election, candidates, parties, and partisan media sources all produced their own fact-checks. These new fact-checkers are driven by partisan goals and have contributed to the emergence of so called “alternative facts”. Given my findings, this new type of fact-check puts citizens at risk of being misinformed about politics by these new fact-check sources.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Debating the Truth: The Impact of Fact-Checking During Electoral Debates’, in American Politics Research.

Featured image credit: Jason Taellious (Flickr, CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2nashVT

_________________________________

Amanda L. Wintersieck – University of Tennessee at Chattanooga

Amanda L. Wintersieck – University of Tennessee at Chattanooga

Amanda L. Wintersieck is an assistant professor of Political Science at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. Her research interests lie in political behavior and political communication. Specifically, she is interested in the effects of political campaigns on voters’ evaluations of candidate, on the role the media plays in citizen’s vote choice, and the conditions that advantage a candidate’s campaign.