Scholarly work has found that there is a consistent gap in political campaign activism between men and women. One potential explanation, grounded in social psychology, is that women have greater exposure to disagreement and resource disparities, which makes them less likely to participate politically. In new research, Paul A. Djupe, Scott D. McClurg, and Anand E. Sokhey examine social networks and political participation over time, finding that while women can be less likely to campaign if exposed to political disagreement, this effect is not consistent over time. They also find that access to social expertise – usually from men – can help women to overcome the effects of resource disparities on their political activity.

Scholarly work has found that there is a consistent gap in political campaign activism between men and women. One potential explanation, grounded in social psychology, is that women have greater exposure to disagreement and resource disparities, which makes them less likely to participate politically. In new research, Paul A. Djupe, Scott D. McClurg, and Anand E. Sokhey examine social networks and political participation over time, finding that while women can be less likely to campaign if exposed to political disagreement, this effect is not consistent over time. They also find that access to social expertise – usually from men – can help women to overcome the effects of resource disparities on their political activity.

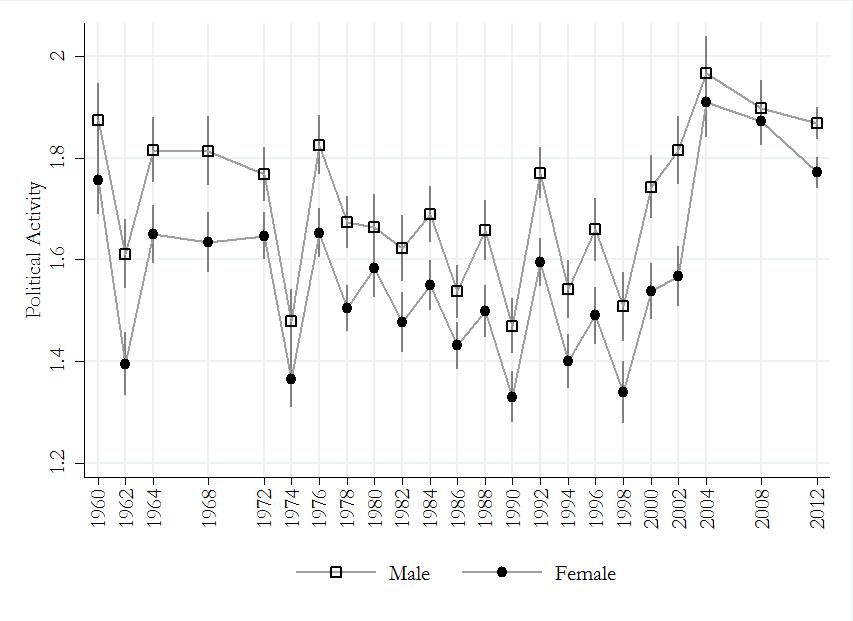

Looking at American politics across the last half century, scholars have consistently found that there is a gender gap in campaign activism (how much people participate in political campaigns). Figure 1 illustrates this, drawing on the American National Election Study time series. As we can see, the average number of activities people engage in has varied by campaign, but the gap between men and women has seldom closed. The gap did close to an insignificant level in 2004 and 2008, but it reopened in 2012. It is against this backdrop that we consider the different roles that social networks may play in shaping the political activity of men and women. Given the social psychology of gender, social exposure to disagreement and expertise should affect men and women differently. We find that despite theories to this effect, such exposure to disagreement does not consistently affect women’s political participation, but that access to social expertise in their political networks can help women to overcome the negative effect of resource disparities.

Figure 1 – The consistent gender gap in campaign activism in American politics, 1960-2012

Note: The ANES summary measure includes giving money to a party or candidate; displaying a button, sticker or sign; work for a campaign; attending a rally; and attempting to influence someone.

Research from across the social sciences has observed different social psychological profiles for men and women, though not all of this work is in agreement or necessarily consistent. For example, some have argued that women speak with a different, more caring and nurturing voice than men’s, perhaps rooted in differences in child development. Some have suggested that women are more likely to “tend and befriend” – rather than engage in “fight or flight” – when subjected to stress. A number of studies have demonstrated that women are more conflict avoidant and tend to give fewer opinions (which can be seen as another way of avoiding conflict).

Consistent results have been documented using the “Big 5” inventory of personality, on which men tend to score higher in assertiveness and openness to ideas, whereas women tend to score higher on agreeableness, extraversion, openness to feelings, and anxiety. Important for motivating our inquiry, the traits on which women score higher – especially agreeableness and extraversion – are just those that would predict sensitivity to social pressure. Personality differences between men and women have also been found to affect such things as earnings, helping to explain wage gaps across decades. One of the mechanisms found to affect wages is the differential experience of men and women in negotiations, which jells with findings concerning women and conflict avoidance. It is little stretch to link these ideas to political activity.

Given that these are fairly well-supported ideas, we found it surprising that research about the effects of social exposure to disagreement on political activity has not considered gender more often. In fact, some of the most cited works on network disagreement and political activity do not engage in a discussion of gender. If women tend to register as more conflict avoidant and more agreeable (to use two closely linked concepts), then we might expect that they would react to social exposure to interpersonal disagreement in ways that would reduce dissonance. That is, interest and engagement in politics should decrease in response to exposure to disagreement in social networks.

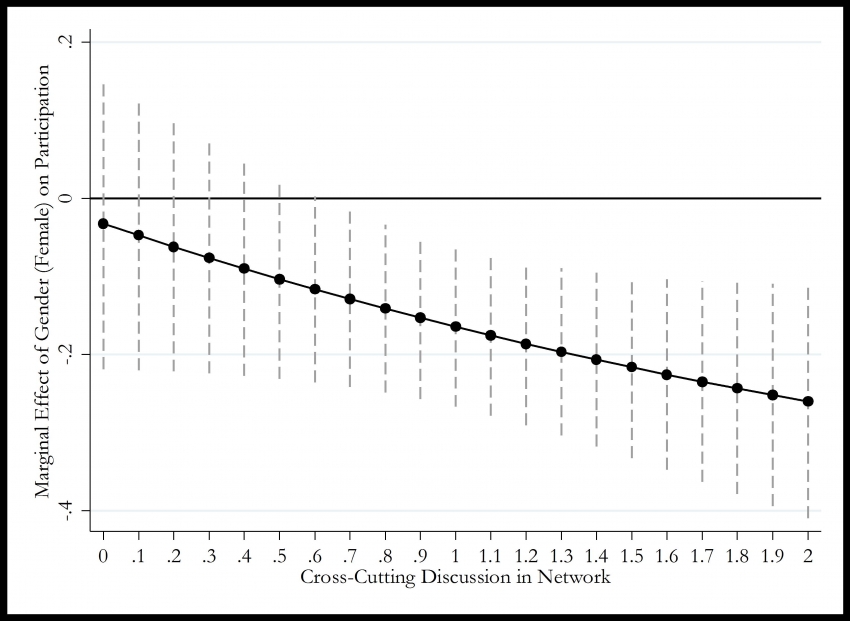

In new research, we focused on these ideas using several familiar studies of the American public. And, as it turns out, several well-known results concerning social networks and political participation are hiding gendered patterns. Figure 2 shows that there is not an even effect of disagreement across the population – instead, women are demobilized by disagreement (relative to men) in a way that is consistent with the aforementioned literature. However, we found that these results from 1992 were not upheld in other years. In fact, in 1996 and 2008, we found evidence that men were particularly demobilized by disagreement (relative to women). In none of the years of our analysis was there a consistent effect across the sexes, which suggests that a simple application of social psychological work to political action is not appropriate.

Figure 2 – Women are demobilized by social exposure to political disagreement

Note: Reexamination of the results of Mutz 2002, using the 1992 Cross-National Election Study

Of course, the importance of social networks for political activity is not limited to disagreement; networks also supply more or less high quality information that can subsidize the costly search for opportunities to participate (and the choices that individuals need to make). Since women have suffered from resource disparities (wage discrimination, and – at least until very recently – more restricted access to/obtainment of higher education), they have tended to have fewer politically-relevant resources than men (i.e., income and education).

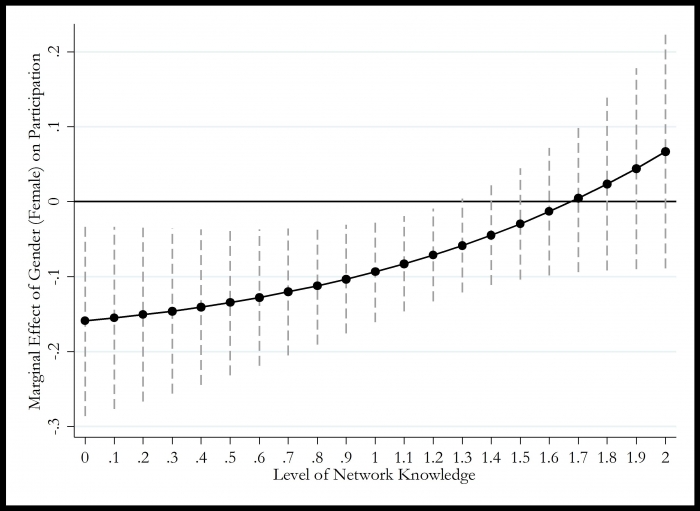

However, if women can borrow the network of a “strategic partner,” they can still gain access to participatory resources. Looking again at these data sets, we found evidence of such “social subsidizing.” Figure 3 highlights one of these findings: that social access to “expertise” in their political networks returns special benefits to women. Without access to expertise (left side of the graph), women participate at lower levels given their resource deficits. However, with more expertise in their networks, women’s political activity becomes indistinguishable from men’s. This effect was consistent across the three years of data (each with somewhat varying study designs) we examined. One thing we would note about this process is that since so many of these (perceived) experts – at least in these data sets – are men, the observed pattern raises additional questions about advocacy and voice. It would be hard to imagine that information exchange with “experts” in networks would not come with social influence/bias. However, this notion has also received little attention from those who study interpersonal political networks.

Figure 3 – Social access to expertise helps women’s political activity rates become equal to men’s

Note: Reexamination of the results of McClurg 2006 using the 1996 Indianapolis-St. Louis study

The degree of polarization among political elites, compounded by the rise of “fake” news, has raised grave questions about the health of democracy at the grassroots of American politics. A robust citizenry should be able to acquire high quality information, withstand exposure to/engage with disagreement, and convey views to government through various modes of political activity. Against this back-drop, the good news is that Americans still talk across lines of disagreement, and in these (now slightly older) data sets we see little evidence that any demobilizing effects are owned by any one group.

Our results cast doubt on any blanket social psychological theory of political activity. Instead, going forward we would stress that there are social logics for men and women that do not line up neatly with “gender psychologies.” We are reminded that we need to think about differences within groups, and are sensitive to concerns about studying “men” and “women.” Still, if we take past literature on its terms (and are willing to overlook some over-simplification), we see that despite expectations that women might step back in the face of interpersonal disagreement, we find a part of American society that is equally resilient and able to draw on available information to communicate with government.

This article is based on the paper “The Political Consequences of Gender in Social Networks,” in the British Journal of Political Science. An online appendix with supplementary discussion and analyses is available here. Original data and do files sufficient to build working data files and replicate the analyses are available at the Harvard Dataverse.

Image credit: We the people by Alice Donovan Rouse from Unsplash

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2o9Va85

_________________________________

Paul A. Djupe – Denison University

Paul A. Djupe – Denison University

Paul A. Djupe, Denison University Political Science, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI and the series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple). He is the editor of Religion and Political Tolerance in America: Advances in the State of the Art (2015) and coauthor of God Talk: Experimenting with the Religious Causes of Public Opinion (2013). Further information about his work can be found at his website, religioninpublic.blog, and occasionally on Twitter.

Scott D. McClurg – Southern Illinois University-Carbondale

Scott D. McClurg – Southern Illinois University-Carbondale

Scott D. McClurg, Professor at Southern Illinois University-Carbondale, holds joint appointments in Political Science and Journalism. His general areas of research focus on political communication, campaigns and elections, public opinion and voting behavior, and American politics. He has published numerous articles in journals such as the American Journal of Political Science, the Journal of Politics, Public Opinion Quarterly, and Social Networks, and is currently an editor of the journal Research & Politics.

Anand Edward Sokhey – University of Colorado at Boulder

Anand Edward Sokhey – University of Colorado at Boulder

Anand Edward Sokhey is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Colorado at Boulder, where he is the associate director of the American Politics Research Lab, and the incoming director of the LeRoy Keller Center for the study of the First Amendment. Anand specializes in American politics, and his work examines the role that social influence plays in voting behavior, political participation, and opinion formation. He has published articles in journals such as the American Political Science Review, American Journal of Political Science, and Journal of Politics.