In states in the Rust Belt and the Southeast, many high schools emphasize courses related to local blue-collar work in order to better prepare students for careers in local industries. In new research, April Sutton, Amanda Bosky and Chandra Muller find that such emphases are often at the expense of college-preparation courses, which in turn has a knock-on effect for female employment rates. Women who are raised in blue-collar communities, and thus who missed out on college preparation courses, face a much bigger wage gap than those who attended high-school elsewhere.

In states in the Rust Belt and the Southeast, many high schools emphasize courses related to local blue-collar work in order to better prepare students for careers in local industries. In new research, April Sutton, Amanda Bosky and Chandra Muller find that such emphases are often at the expense of college-preparation courses, which in turn has a knock-on effect for female employment rates. Women who are raised in blue-collar communities, and thus who missed out on college preparation courses, face a much bigger wage gap than those who attended high-school elsewhere.

What should schools teach our nation’s youth? What type of training best prepares all students for labor market success? These questions have fuelled contentious academic, political, and public debates for over a century. While some argue that schools should prepare all students for a college degree, others advocate for a re-emphasis on career and technical training, especially in better-paying blue-collar jobs.

In the policy realm, states in the Rust Belt and Southeast have relaxed academic graduation requirements. Some states allow blue-collar-related training to satisfy math and foreign language requirements. Moreover, alongside his promises to revitalize US manufacturing, President Trump and members of his cabinet have pledged to strengthen career and technical education, dismantle Common Core, and allow local decision-makers to govern what schools teach.

Gender gaps and economic opportunities for women have been glaringly absent from this discourse. This is disconcerting given that blue-collar jobs—some of the few remaining sub-baccalaureate jobs that provide living wages—are highly male-dominated. What’s more, our estimates show that the small share of millennial women employed in blue-collar jobs earn wages that are only 78 percent those of their male counterparts.

In recent research, we add a gender and spatial perspective to reinvigorated high school training debates. Our study compares the outcomes of men and women who attended high school in blue-collar communities, places where blue-collar jobs remain prevalent. We found that schools in blue-collar communities emphasize courses related to local blue-collar work at the expense of college-preparatory courses that prepare students for four-year college.

Considering the male-dominated nature of blue-collar jobs and women’s greater returns to college, does this curricular trade-off in blue-collar communities have gendered consequences in the labor force? We find that it does.

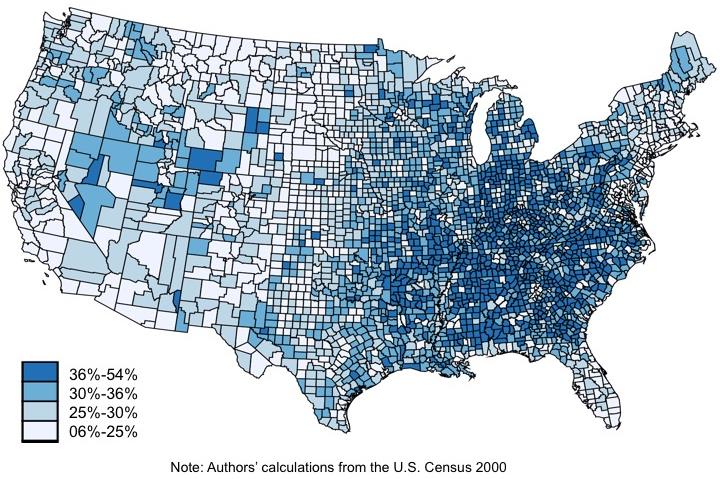

We used the Education Longitudinal Study of 2002, a nationally representative sample of high school sophomores collected by the US Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics. We linked these data to county labor market indicators from the US Census 2000 to examine whether high school training in blue-collar communities has gender-divergent consequences. We defined blue-collar communities as counties that fell in the top quartile (top 25th percentile) of our sample for the share of local workers employed in blue-collar jobs (i.e., production, construction and extraction, transportation and material moving, and installation, maintenance and repair).

Figure 1 – County variation is shares of Blue-Collar workers

As the map shows, these are communities as diverse as Conecuh County in Alabama, Potter County in Pennsylvania, and Lincoln County in Wisconsin, but they share the trait that blue collar jobs make up a sizable share of the local labor force.

Our analyses adjust for factors that may confound the relationships between the local labor market and our education and labor force outcomes, including students’ socioeconomic and academic background, school characteristics, and local labor market traits (e.g., unemployment rate).

Gender-divergent outcomes

We found that both men and women who attended high school in blue-collar communities were less likely to attend a four-year college relative to their counterparts from communities with the lowest concentrations of blue-collar workers (which we refer to as non-blue-collar communities). Importantly, only women from blue-collar communities appeared to suffer labor force penalties.

Men from schools in blue-collar communities had higher rates of blue-collar-related course-taking and blue-collar employment relative to their male counterparts elsewhere, partially due to differences in their high schools’ course offerings. At around age 26 these men earned wages similar to men who attended high school elsewhere.

In contrast, women from high schools in blue-collar communities were less likely to be employed in professional, managerial, and finance occupations than their female counterparts elsewhere. In fact, they were less likely to be working at all. And when they did have jobs, they had higher wage penalties compared to their male peers in blue collar communities and women from non-blue-collar communities.

In other words, women who were raised in blue collar communities faced a wider gender wage gap in early adulthood (15 percent) compared to women who attended high school in non-blue-collar communities (2 percent).

Our study shows that women in blue-collar communities faced worse outcomes not due to their high schools’ blue-collar curricular focus as such, but because it came at the expense of the college-preparatory courses that encourage four-year college enrollment and completion. With weaker college preparation and fewer attractive options in the sub-baccalaureate labor market than their male peers, we found that high school training in blue-collar communities left young women in the lurch.

Implications

In sum, we found that high school training in blue-collar communities disproportionately penalized women and exacerbated gender inequality in the labor force. The patterns we observed in blue-collar communities point to times of yore. Young women’s education and labor market outcomes in these places misalign with many national trends that show narrowing or reversed gender gaps, and this is partially because their schools’ course offerings aligned with the local economy.

As for young men, our results may provide some support for some scholars’ and policymakers’ promotion of blue-collar jobs as pragmatic alternatives to the kinds of jobs often obtained after attempting a bachelor’s degree.

At the same time, our labor market snapshot is in early adulthood, and college graduates’ wages will rise steadily across the life course while blue-collar workers’ wages are likely to stagnate. Given that men in blue-collar communities were less likely to attend a four-year college, they may also have few options to obtain other well-paying jobs in the face of economic downturns and looming automation.

Overall, our research shows how gender and the (gendered) labor markets where students attend high school complicate college-for-all debates. While the image of disenfranchised men in blue-collar communities has been unremittingly promulgated over the last several months, the results of our study call for a concern about women in these places. High school training debates and efforts to revive manufacturing must consider the effects on women and gender inequality in the labor force.

Featured image credit: Flip Schulke, 1930-2008, Photographer (NARA record: 2435383) (US National Archives and Records Administration) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

A version of this article first appeared on the Work in Progress blog and is based on the paper, “Manufacturing Gender Inequality in the New Economy: High School Training for Work in Blue-Collar Communities” in the American Sociological Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2obkev3

_________________________________

April Sutton – Cornell University

April Sutton – Cornell University

April Sutton is a Frank H.T. Rhodes Postdoctoral Fellow at Cornell University. In the summer of 2017, she will begin her appointment as Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at UC San Diego.

Amanda Bosky – University of Texas at Austin

Amanda Bosky – University of Texas at Austin

Amanda Bosky is a graduate student in the Department of Sociology and a NICHD Pre-Doctoral Trainee in the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

Chandra Muller – University of Texas at Austin

Chandra Muller – University of Texas at Austin

Chandra Muller is Alma Cowden Madden Professor of Liberal Arts in the Department of Sociology at the University of Texas at Austin and a visiting scholar at the Russell Sage Foundation in New York during the 2016-17 academic year.