Pundits appear eager to portray the partisan battles waged during the 2016 U.S. presidential election as reaching new lows where dirty politics were concerned. Yet despite massive media interest in dirty politics and academic investigations into many aspects of this soft underbelly of democratic elections, very little is known about the way the public responds to news about dirty politics—whether the misdeed is a stolen yard sign or a more serious allegation of election fraud. Research by Ryan L. Claassen and Michael J. Ensley reveals good reasons for monitoring public reactions to dirty politics. The public are not neutral when news about a political misdeed surfaces—instead the public see the misdeed through partisan lenses. This research raises new and interesting possibilities regarding the implications of Trump’s allegations of election fraud and likely public response to ongoing reports about investigations into alleged collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia.

Pundits appear eager to portray the partisan battles waged during the 2016 U.S. presidential election as reaching new lows where dirty politics were concerned. Yet despite massive media interest in dirty politics and academic investigations into many aspects of this soft underbelly of democratic elections, very little is known about the way the public responds to news about dirty politics—whether the misdeed is a stolen yard sign or a more serious allegation of election fraud. Research by Ryan L. Claassen and Michael J. Ensley reveals good reasons for monitoring public reactions to dirty politics. The public are not neutral when news about a political misdeed surfaces—instead the public see the misdeed through partisan lenses. This research raises new and interesting possibilities regarding the implications of Trump’s allegations of election fraud and likely public response to ongoing reports about investigations into alleged collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia.

The Trump Administration has challenged traditional American democratic norms in multiple ways. Near the top of this list is the Administration’s challenge and rejection of facts and information that is generally accepted, coupled with disdain for the mainstream media. Now many in the media and the public are discovering what psychologists and political scientists have long known: people engage in motivated reasoning, which means that citizens are biased information processors who uncritically accept favorable information about their party or team, but discount or reject unfavorable information about their side. We have concern that runs deeper than this regarding motivated reasoning. While it is not new nor very surprising that people interpret the meaning of facts and deem their importance according to their partisan orientations, it is rightfully concerning that the facts themselves are a matter of debate. Does this tendency towards motivated reasoning extend to areas where clear ethical norms define what is acceptable behavior in democratic politics?

To gain leverage on this question we studied individuals’ reactions to “dirty” campaign tricks through a survey experiment, which is presented in our recently published article in Political Behavior. We define ‘dirty tricks’ as actions taken to undermine the opponent’s electoral chances through tactics that would be deemed unethical (and typically illegal). The survey experiment was part of the 2010 Cooperative Congressional Election Study, which provided a nationally representative sample of one thousand American voting age citizens. Survey respondents were exposed to one of two brief news story vignettes about a dirty political campaign trick (there was also a control group that did not see any story). One story involved stolen campaign yard signs, while the other trick involved an automated phone call scheme wrongly informing the opponent’s likely supporters about when the polls were open. We chose these treatments since one trick (the phone calls) seems seriously more damaging to the electoral process than the other trick.

To investigate whether partisans apply different standards to dirty tricks perpetrated by co-partisans, the experiment also manipulates the party of the perpetrator of the dirty trick. Respondents were randomly assigned to hear a story where the campaign that authorized the phone calls or stole the yard signs was affiliated with the Republican or Democratic Party. After the respondents were asked to read the story about the dirty trick, they were asked to evaluate the seriousness of these types of actions and whether the actions were justifiable.

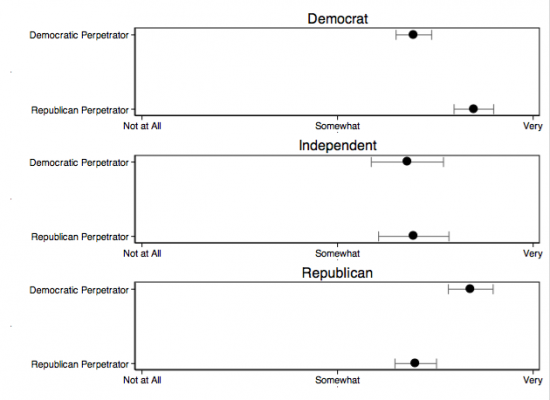

The experimental results reveal that motivated reasoning is present even when it pertains to ethical issues. When a citizen that identifies as a Republican sees a story where the Democratic Party is the perpetrator of a dirty trick, he or she is less likely to feel the tactic is justified and views the offense as more serious than a citizen who identifies with the Democratic Party (see Figure 1a and Figure 1b below). The same is true for Democratic identifiers who see a story where the perpetrator is the Republican Party: they see the trick as more serious and are less likely to feel it is justified. Bear in mind, the descriptions of the dirty tricks are identical, save the description of the partisanship of the perpetrator.

Figure 1. Assessments of the seriousness of the dirty trick described in the vignette

Figure 2. Assessments of whether the dirty trick described in the vignette was justified

Apart from demonstrating partisan motivated moral elasticity, the results also shed new light on the mechanisms behind motivated reasoning. Independents who are exposed to a dirty trick vignette respond in the same ways as Republicans that see a story with a Republican perpetrator and Democrats that see a story with a Democratic perpetrator. In other words, partisans deviate from the behavior of Independents when exposed to news of the opposing party committing a dirty trick. There seems to be a strong dose of negative partisanship – when the opposing party commits a dirty trick, individuals arrive at exceptionally negative judgments.

According to the theory of motivated reasoning, subjects typically “discount” information that causes cognitive dissonance (good news about the opposition or, in our experiment, bad news about one’s party). We note that partisans respond to bad news about their party in the same way as Independents. If “discounting” means actively doing something, then they should deem the trick less serious and more justified when it is done by their party than independents do. We find little evidence of discounting in our experiment. In some ways this is good news. Partisans do not appear to “acquit” their candidates in the court of public opinion for misbehavior on the campaign trail.

However, we do find that partisans respond in a motivated way to bad news about their partisan opponents—consistent with expectations about how subjects will deal with news that follows a congenial cognitive pattern (good news about one’s party or, in our experiment, bad news about the opposition). Unfortunately, this pattern of motivated reasoning has more ominous implications when it comes to dirty political tricks. If negative reactions to cheating are so demoralizing to opposition partisans (relative to the partisanship of the perpetrator) that they disengage from politics, the cheater reaps a perverse public opinion reward for cheating as opposition voters stay home. However, we hasten to add the link between victim partisans’ reactions to dirty tricks and demobilization is not well established empirically. In fact, if reactions to dirty tricks have a mobilizing effect on victim partisans, a candidate would benefit from accusing the other side of foul play—equally troubling if the accusation is unfounded (more on this in a moment).

Two additional results are noteworthy. First, there were not any appreciable differences between the two types of tricks, even though we expected individuals to react differently to the automated phone calls because such robocall operations are a much more serious offense. Second, we did not find that overall trust in government is severely affected by these political tactics. When we compared individuals that were exposed to a dirty trick to the control group that did not see a vignette about a dirty trick, there were only minor differences in the levels of trust between the two groups.

Returning to ongoing developments, what does one make of public reactions to Trump’s pre-election accusations of impending election fraud? First, we would like to note that our experimental treatment falls well short of stealing elections. While we were heartened to find that Americans’ general attitudes, such as trust in the government, were unfazed by news of a dirty trick on the campaign trail, we recognize that trust could be more vulnerable in the face of more serious problems. If accusations of Democratic Party cheating undermined Republicans’ trust in the system to the point of disengagement, then the ploy would have backfired. On the other hand, if exceptionally negative reactions to such accusations were motivating to Republicans (e.g. stimulated turnout), then Trump’s effort to fire up his base would have been successful. Our experiment reveals that Republicans would deem Democratic cheating to be exceptionally serious and unjustified and that it is unlikely to undermine more basic orientations toward the political system. Additional study is needed to assess whether negative reactions to news about dirty tricks perpetrated by opposition partisans stimulates political participation.

Finally, we also think our results can inform expectations about public response to the unfolding allegations of collusion between the Trump campaign and the Russians. Once again we can be confident that the opposition (in this case Democrats) will be exceptionally incensed. However, in this case the experiment also points to outrage among Republicans, assuming they do not discount. In any case, we note that news of dirty tricks is not the be-all-end-all — the public response can be every bit as titillating.

This article is based on the paper Motivated Reasoning and Yard-Sign-Stealing Partisans: Mine is a Likable Rogue, Yours is a Degenerate Criminal in Political Behavior.

Republican election yard signs by TheDigitel Beaufort is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2vxjsYY

_________________________________

Ryan L. Claassen – Political Science at Kent State University

Ryan L. Claassen – Political Science at Kent State University

Ryan L. Claassen is Professor of Political Science at Kent State University in Ohio. He teaches a variety of courses in the areas of quantitative research methods, American politics, and political behavior – at both the doctoral and undergraduate levels. He is the author of “Godless Democrats and Pious Republicans? Party Activists, Party Capture, and the ‘God Gap’” (Cambridge University Press) and his work work has appeared journals such as American Politics Research, The Journal of Politics, The Journal of Political Science Education, Political Behavior, Political Research Quarterly, Public Opinion Quarterly, and PS: Political Science and Politics.

Michael J. Ensley – Political Science at Kent State University

Michael J. Ensley – Political Science at Kent State University

Michael J. Ensley is Associate Professor of Political Science at Kent State University in Ohio. His research and teaching interests include the U.S. Congress, elections, voting behavior, and statistical methodology. He has published journal articles in many different journals including The American Journal of Political Science, Political Behavior, Legislative Studies Quarterly, American Politics Research, and Public Choice and is currently working on a book entitled Beyond the Left-Right Divide (with Edward Carmines and Michael Wagner). He received his Ph.D. from Duke University in 2002.