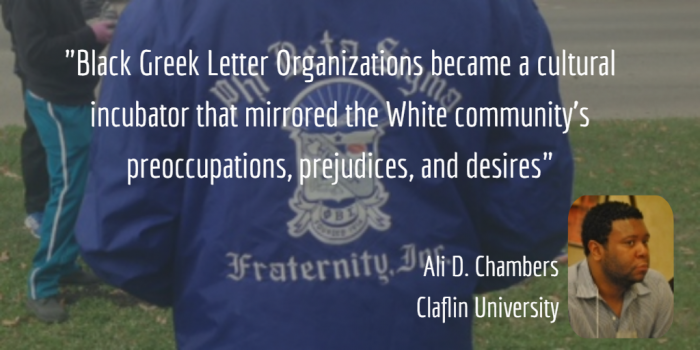

Now more than a century old, Black Greek Letter Organizations – fraternities – have more than 800,000 members. But are such organizations an asset or do they work against African American culture? Ali Chambers argues that rather than unifying the Black community against the effects of racial prejudice, they have merely become a vehicle for Blacks to assimilate into White culture and society, and a means to create a self-perpetuating Black oligarchy.

Now more than a century old, Black Greek Letter Organizations – fraternities – have more than 800,000 members. But are such organizations an asset or do they work against African American culture? Ali Chambers argues that rather than unifying the Black community against the effects of racial prejudice, they have merely become a vehicle for Blacks to assimilate into White culture and society, and a means to create a self-perpetuating Black oligarchy.

In the past 5 years, there has been a resurgence of research surrounding the philosophy and mission of the Black Greek Letter Organization (BGLO). While my work suggests that the rites of passage of the Black fraternity—which include ancestor veneration, rebirthing concepts, and dance performance—can mirror those characteristics found within traditional West African communities, new theories suggest that BGLOs should be critiqued as social movements

BGLOs are some of the most influential organizations in the country. Collectively, these organizations claim approximately 800,000 members, with many coming from the social elite of Black culture. Each year, they offer countless scholarships and conduct thousands of service programs. Accordingly, many of the staunchest supporters of BGLOs not only insist that their existence is a valuable asset to society but also stress that these organizations, which include writers, social activists, educators, and civil rights leaders, are historically linked to the success of the African American community.

Conversely, many of their harshest critics maintain that the activities of organizations that have included secret meetings, selective membership, and a preference for lighter complexions have allowed Black elites to create a separate privileged society based on snobbery and arrogance and have thus enabled these organizations to perpetuate the vicious cycle of racial prejudice and White supremacy.

Historian and sociologist W.E.B. DuBois at times openly condemned Black fraternities. During a 1930 commencement address at Howard University, DuBois stated, “Our college man today is, on the average a man untouched by real culture. He deliberately surrenders to selfish and even silly ideals, swarming into semiprofessional athletics and Greek letter societies…we have in our colleges a growing mass of stupidity and indifference”.

Consequently, it is the conformity to Western values and social norms that has created the controversy surrounding the initial purpose of the BGLO. Between 1906 and 1920, eight of the most prominent BGLOs were established. Many scholars have questioned whether these organizations were created in the hopes of unifying the Black community against the harmful effects of racial prejudice or whether they were formed by young African American students in order to gain acceptance into American society by emulating existing White organizations of the period.

The creation of the Black fraternity had a dual purpose. First, these organizations were established for the greater goal of pooling the resources of African Americans in the hopes of acquiring an education. Second, these organizations were formed as an attempt by Black students to gain acceptance into American society, that is, the campus community, by emulating or creating organizations that mirrored preexisting White organizations.

From as early as the 1700s, Blacks in America have believed that there were conditions placed on them to justify equality or citizenship. These included acceptance of Christianity, participation in the military, obedience to Republican or Democratic principles, and economic development. Taken together, these can be encapsulated as the “be like us” theory of equality—that Blacks would be equal to Whites when they become like Whites. Another approach was an attempt to adjust all thought and action to the will of the greater group—assimilation into White culture and society. A third path was a conscious effort at self-realization and agency.

Racial uplift was the Black elites’ response and challenge to White supremacy. It was both a contradictory position that sought to affirm that African Americans belonged to a racially subordinated caste while also serving as a model for African Americans aspiring to redefine themselves as members of a higher social class. Racial uplift sought to refute the view that African Americans were biologically inferior by incorporating the Black community into respectable categories of Western progress. Generally, Black elites claimed to possess class distinctions from other African Americans. Moreover, the presence of a “better class” of Black people indicated racial progress. They believed that the improvement of African Americans’ material and moral condition through self-help would diminish White racism.

“Chicago Urban Conservation Partnership – Phi Beta Sigma” by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Although the BGLO had the specific aim of liberating the Black community from inferior positions as second-class citizens, many viewed these organizations as a means for the Black bourgeoisie to create and maintain privileged status and recognition within the Black community. Nevertheless despite their use of elitism and snobbery, the popularity of the Black fraternity was furthered by both the exclusivity of these organizations and the notion that they helped to produce a better class of Black people.

Rather than adhering to their own traditions and cultural attitudes, many members of BGLOs abandoned traditional African views and adopted the views of the dominant Anglo culture. While it is true that BGLOs were social organizations that utilized some elements of traditional African culture and combined them with elements of European culture, these organizations, in the end, used their power and influence to create a self-perpetuating Black oligarchy.

Although the BGLO has served as a safe haven for Black thought and allowed for new attitudes regarding the future of the Black community, these organizations were conceived within Western culture, which over time reflected the views of a racist society and thus became a hindrance to the furtherance of the Black community. In this respect, the BGLO became a cultural incubator that mirrored the White community’s preoccupations, prejudices, and desires. As a result, the BGLO became an oppressive organization that was at times used to suppress African characteristics and uphold the ideals of White supremacy.

This article is based on the paper ‘The Failure of the Black Greek-Letter Organization’, in the Journal of Black Studies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2x3siQf

_________________________________

About the author

Ali D. Chambers – Claflin University

Ali D. Chambers – Claflin University

Ali D. Chambers, PhD is an assistant professor of African American Studies at Claflin University in Orangeburg, SC. His work and research is concentrated on the historical and cultural impact of the Black Greek-letter Organization. Currently Dr. Chambers is completing his book, Finding Consciousness in the Black Fraternity.

Thanks for the article Mr. Chambers. I definitely see W.E.B. DuBois views concerning Black Greek Letter Organizations today and agree somewhat with his condemnation of the groups about elitism that is often seen yet today. Yes each organization should believe in the order that caused them to exist but that should only be a part of it. For sure it’s a great thing that Blacks in America are no longer enslaved as the property of someone else. When slavery ended America did not see all efforts through to incorporate former slaves into society and today Black America’s short coming can be linked to the abuses from slavery. The lack of education, economic opportunities and social injustice still exist today for Black America. The words of inferiority still echo for many in the Black Community and so many in the community just do not even try for fears of failure. Now among some of those in the Black Community who try and meet resistance, they want to shout racism. The point of my post is Black fraternities and sororities should be about uplifting the next generation and not self glorification. Every city where there is an HCBU, outreach should be happening to support the community and Greek Organizations should be the leaders. Also graduates should be supporting their school financially if only with $100.00 year.

First I would like to thank everyone for their comments, they were well received. I encourage you to continue contributing to the issue at hand. Regarding the Black Greek-letter Organization, I think is important to understand that any organization and/or institution created within a Eurocentric society will over time reflect the ideals of that society. Hence if a society is racist, sexist, or homophobic these ideals will soon become ingrained within the social consciousness of the organizations created within that society. I think we can all agree that HBCUs were created to educate and uplift African-Americans. However there are some HBCUs that have become elitist and that have marginalized certain elements of the black community…in the past there were certain HBCUs that did not admit Blacks with dark complexions. Likewise there are some black churches who have marginalized and catered to certain elements of the black elite…remember the brown paper bag tests? Unless we are under the impression that the black church and the HBCU can do no wrong; if our olfactory senses have rendered us numb to the scent of our own malfeasance, we should allow these organizations to conduct their business without any criticism or oversight from the communities they were intended to serve.

Does this mean we get rid of all black churches or all HBCUs, certainly not. It does mean that we should be critical of these organizations; that we should question their activities, praise them when they do right, and condemn them when they do wrong. We as African-Americans should be critical of all institutions within the black community so that these institutions can continue to serve the greater good of providing support and resources for African-Americans.

Fabulous article sir! The bottom line is greek organizations are self-aggrandizing and ignorant. You can’t be truly pro-black and subscribed to these groups … it’s a contradiction which unfortunately is the norm in tragic modern society.

Your research on BGLOs are identical to mine. I wish you would’ve dived into the damaging effects of hazing and the collective embarrassing academic achievement of BGLOs … especially amongst BGLO fraternities. It’s funny how they claim to be the “cream of the crop” but more often than not they struggle to maintain the lowest possible respectable GPA (3.0).

And of course, most BGLO members are going to denounce the article b/c their identifies and self-worth is wrapped into those greek letters. You exposing the BGLO for what it really is, is seen as a personal attack. But if they don’t like the truth then that’s their problem no one elses … let them whine.

But I loved it, I’m gong to share it, and I’m happy to see there are other black people who did not drink the “BGLO kool-aid” LOL.

Now moving away from BGLOs, to HBCUs. I’ve always heard that some HBCUs practiced the Brown Paper Bag Test but there’s not enough evidence to suggest that was definitely the case. The place where it’s said to be the most prevalent was “The Mecca” (Howard University) but Howard has always had people of darker hues on campus just by looking at archive pictures (I did the research). BGLOs definitely practiced the Brown Paper Bag Test b/c my Creole grandmother told me she was shown preferential treatment by AKAs when they were recruiting b/c she was one a few girls on her HBCU campus to have strong Eurocentric features with hazel eyes, dirty blonde hair, pale skin. Please keep in mind her grades were subpar and she was a loner, she only went to college to find a college educated husband which she did. But again there’s not enough evidence to suggest HBCUs barred dark skin people from entering … plus it doesn’t make financial sense. They would be turning away NEEDED tuition dollars that would help run schools that were underfunded.

WHY IS DuBOIS SO CRITICAL OF A SYSTEM THAT HE LATER BECOMES A PART OF??? TO QUESTION THE SYSTEM IS LIKE QUESTIONING THE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM, BECAUSE MOST OF YOUR INSTITUTIONS ARE RAN BY THESE PEOPLE…

This is unfortunate–and very misleading. In all honesty I stopped and skimmed after I read “between 1906 and 1920, eight…” Bruh!!!!! How can you pen this article and be so lazy to know when these organizations were founded. The Sigma Ladies of Sigma Gamma Rho were founded in 1922. Of the nine members of the NPHC six were founded at Historical Black Colleges and Universities. (Howard University and Morgan State University respectfully) Kappa Alpha Psi was founded at Indiana University, Sigma Gamma Rho was founded at Butler University, and Alpha Phi Alpha was founded at Cornell University. These organizations have given more of themselves in their existence than they have ever glorified themselves due to the success of their efforts. Your entire premise is intellectually dishonest. No organization is the panacea for all the ails of the Black Diaspora. You state that Black Fraternities claim 800,000 in membership–I can insure you that is since 1906 and not the living membership today.

But who said that you and your opinion and critique of the historic civil rights organizations that have branded themselves as Fraternity or Sorority was warranted? How are you qualified to cast such aspersions in a reckless and inaccurate manner? I have been a member of my fraternity for over 28 years. The only people I have ever heard claim BGLO’s are divisive are divisive individuals. It seems that your premise rest solely on the notion that 1 cure fixes the ailments of our society. You speak as if having variety is a bad thing. I most certainly believe that each of our BGLO’s has a character, and that character fits the personality and style of it’s members. Just like a church–you join where you feel you belong and where you are most apt to do your best work. We are all working for causes that impact our community–we need each other and our community needs all of our efforts. But those causes are not the burden solely of the BGLO or the Black Church, or the NAACP or the Urban League or the Council of Negro Women -we are not in competition.

My suggestion to you Sir, is support those entities doing work in our communities. Pray for their success or simply let them be. Just because it’s not for you doesn’t mean it’s not being impactful to some within our Diaspora. You do more damage opposing organizations that earnestly are trying to do governments job with a zero guaranteed budget. 800,000 members–even if that were true, you do realize that there are over 48,000,000 Blacks living in America?

You spoke with the dopeness!

I agree ! The same ole anti-BGLO sentiment and it’s gotten very old…..

Very well articulated Brother Hicks. Yet another BGLO attack from those that have not pledged or been initiated. As a fellow greek and proud member of The Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Incorporated, you and I know, our BGLO’s at the core were ALL created with one common goal – the edification and uplift of our race and communities. We all need to read Bro. Dr. DuBois’ essay, “The Talented Tenth”. It is quite clear that he was referring to the BGLOs as the subject of his thesis.

Kevin D. Brown

Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Incorporated

Dallas, Texas

I have to respectfully disagree to a large extent with this article. I believe that there are “pockets” in every BGLO that may possibly show what the writer is referring to but in large, I see plenty of mentoring and various community projects that BGLOs do on a constant basis. From financial seminars to college tours, tutoring, mentoring and scholarship drives for high school kids just to name a few. As a proud member of Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity, Inc., we are constantly working in the mentoring department with young men (middle school and high school). I read on a consistent basis of various chapters all over the country mentoring young men, having back to school functions, leadership and team building projects and providing exposure to various schools, jobs and other opportunities that these young men may not otherwise get a chance to experience. The elitism, if any, is so small in comparison to the rest of the chapters and provinces that make up the Fraternity. We are constantly uplifting the future generations socially, financially, morally, spiritually and through education. Ultimately, all I’m saying is, the over generalization that this article appears to cast is not accurate. Overall, I KNOW what Kappa does but I would also dare to venture out and say that AS A WHOLE………..the BGLOs do quite a bit in their respective communities. I would invite the writer of this article to investigate and reach out to the BGLOs and have them show him what’s really going on. He may write about the BGLOs in somewhat of a different light afterwards

Mr. Chambers:

In your article, you equate Black fraternities and sororities with the White ones.

Is that merely because they all use Greek letters?

Having a PhD, you should at least know that’s about ALL that they have in common.

I suggest that you dig much, MUCH deeper than the surface to see that there is no comparison between the 2.

For example, one of my White co-workers recently mentioned that “he USED TO BE a member of “ABC Fraternity” (I can’t recall the name of his FORMER frat). But the only time a Black person refers to a FORMER NPHC fraternity of their, is because they were EXPELLED from it.

I am very disturbed of the depiction of BGLO’s as described by this PHD.. I find his research flawed and inaccurate. I am a first generation college graduate from a family of 7 brothers and 4 sisters, where both my father,s and mother’s family did not complete high school. Elitism has never been a goal; however, service and duty to uplift mankind has been instilled. During service and duty to mankind through an organizational structure is far better than individual self gratification. Even, DuBois was part of an organization to uplift mankind, the NAACP that was founded by Jewish folk and he being invited to head up the “Crisis Magazine after the failure of the Niagra Movement.

“Between 1906 and 1920, eight of the most prominent Black Greek-letter organizations were established.”

You should ALSO realize the the “Great Eight” were ACTUALLY founded between 1906 – 1922, not 1906 – 1920 (Sigma Gamma Rho Sorority, Inc. was founded in November of 1922).

With all of the community service which is completed by each organization, how does one come to this assumption? With young African American male mentoring occurring in the community, how do you assert any separation between community and fraternity? Now, I can see how a PhD no longer has his ear to the ground of a community, because he is locked in his ivory towers of academia… that makes sense.

You take a DuBois piece, which speaks towards the stupidity of the college student because they want to partake in a system created to provide support for others. See, the American Negro was not all in a great financial place. Some achieved, but a Mass. negro did not live the same as a Miss. negro. People needed a support system, and these orgs provided such a system for these men/women. Now, not all fraternities were founded on HBCU’s and sometimes, “we are all we got.”

Dubois used a thought which was not his own. Henry Moorehouse propagated his theory of the talented 10th Tenth, not DuBois. But yet, his claim was to take the smartest and brightest to promote the Africans cause during that period. Yeah, wake up your consciousness Mr. Author and rethink your thesis. People of color have always looked to move up and out. This started more-so in the “Silk Stalkings Churches” and not via the frat/sorority.

I believe this analysis of BGLOs is not accurate. We are not imitators of white Greeks because our mission and purpose extends beyond the college campus. BGLOs are a support system to the Black community and to individual members of their BGLO. As a proud member of Alpha Kappa Alpha my sorority sisters have assisted me financially and when I needed them the most. Moreso than my own family or church. Not all BGLO members are of the elite. I am a first generation college student from a working class background where my mother nor father attended college. We are not monolithic and the stereotypes need to cease about BGLOs.

I agree with the comments that spoke positively about BGLO’S. So maybe the color thing was used during a certain Era but I am a Black Nubian Cushite and in a fraternity. Most of us joined probably as undergrads and became members of the BGLO that best fit our personality. Going to a predominately “W” University what u missed in your article is that we were a tight knit inclusive community. We were not elitist because we couldn’t afford to be. We weren’t trying to assimilate to the “W” culture, we were trying to make it by helping each other. Being there for each other and building our own community. Even within the 2000 Blacks at the school only 8-10% were in BGLOs. Who do u think came out to our parties? Yeah we did, but it was the majority of the Non-BGLO’s.

You quickly scathed past the good that we do. You failed to mention the entire context in which Mr. Dubois was soeaking. As a scholar how could you only pick a soundbite, even you should know better?

Oh and by the way when I entered the university it was the Black Brothers in the BGLOS who navigated me through. Not to pledge their frat but to set my course so that I may do the same for new students and pass that tradition down.

When I see some of these guys at Homecoming every year, though it has been almost 38 years since I crossed the burning sands I almost stand in tears as I see their faces and reflect on how they helped shape me into the man I am today. Why did u not mention the bond we have not just in our own organization but with each other? I had three best friends in college and all four of us pledged a different frat. To this day we can be with our own Bros, but when we see each other it’s a beautiful thing! So it is with the sororities

To be an oligarchy you have to be an oligarch which translates into the wealth few Blacks see individually. We r not an olgarchy!

As a member of Omega Psi Phi, for 30 years, and having pledged at the Oldest HBCU, Cheyney University, I can assure you the “one size fits all” characterizations are not even close to my experiences with dozens of national and international chapters.

I can also confirm that millions in scholarship money is given to aspiring black students attending colleges & universities all over the world. Also millions more in time and money are given to black communities, every year through Thanksgiving Turkey give aways, Talent hunts, mentoring, sports and academic programs, Civillian Achievement Ceremonies and many more events, by my fraternity alone.

I read and then scanned after becoming quite annoyed. If this man has a PHD he should understand the need to research and then look at his data in a subjective manner. He is wrong on so many levels. The idea that Black Greek Organizations resulted from the need to be like ‘whites’ is ludicrous. Completely opposite of the reasons for our inception. His report is subjective and false.

I am a proud member of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority Inc. I know why and how we began our endeavors of service, academic excellence and sisterhood.

You start out your article by quoting a member of a BGLO out of context. You seemed to have failed to review the histories of the BGLO’s, the reasons advanced by their founders for their founding and the ideals upon which they were founded, but most of all, you have completely ignored the significant accomplishments of the members of these organizations and their contributions to the advancement of black people. The major civil rights figures who fought to advance black people and to overcome oppression were all members of BGLO’s — every one of them. Martin Luther King, DuBois and Thurgood Marshall were Alphas. J Phillip Randolph, Jessie Jackson and Vernon Jordan were Ques. Abernathy and H. Rap Brown were Kappas. Huey Newton was a Phi Beta Sigma. And those are just the men. The black women who led the struggle were also members of black sororities. Moreover, the one thing that has been most impressive to me about the founders of these organizations has been the high ideals and principles that they established as guides to success in life. The brilliance in expression of these ideals and principles by young college students who founded these fraternities and sororities is unparalleled today. Their academic achievements as well as extra curricular accomplishments and, upon graduation or leaving college, their achievements in all walks of life have been the rule not the exception. And where did you get that “light skinned” members is the norm thing? Dark skinned people, like me, joined BGLO’s as well. There are legitimate criticisms of BGLO’s from within as well as without; but your points were not well taken.

These comments show just how a hit dog will holler. Erosion of the individual is a sad thing to see. Cognitive dissonance and denial seem to cloud any true progressive dialogue as soon as you criticize BGLOs. They are problematic in ways that if the grievances were addressed and corrected, instead of met with defense, we might not continue to have these conversations. I wonder how sustainable this model is in this social climate. I think this generation values individuality immensely. We see socially conscious and engaged youth operating without membership to any organization (not just Greek.) We also see youth with artistic expression who may not fit the Greek mold. Where do they anticipate cultivating future membership.

Its other bglo organizations our there besides the Devine Nine I’m a member of Beta Phi Pi Inc. Founded in 1986 we do alot of community service projects and mentoring in the community

The claims in this article are laughable. There is an incredibly negative perception of BGLOs by people who are not in them. Striving to maintain high scholastic standards, mentoring youth, giving back to the community and becoming the very pioneering doctors, lawyers, educators and scientists our children learn about in school is why these organizations are important. As a proud member of Alpha Kappa Alpha, Inc., being a positive example, making strides in my career and being giving back to our community theough mentorship and service is exactly why I joined. So many great black historical figures were members of a BGLO – including DuBois – yet you focus on one aspect of the past. As long as we ALL are working to empower our community – greek or not – it shouldn’t mattter. Joining may not have been your cup of tea, and that’s absolutely fine. Just understand that diminishing the efforts men and women who want whats best for our community just like you do is more divisive than anything.

Big picture wise, If you BGLO members defending your orgs use this same energy to oust out the “boujee” and “elitist” members of your respected organizations, then this critical article would not have to exist at all.

Bottom line

Yea Chuck…and they should let YOU go through all of the organizations and pick out who YOU think is ‘boujee’ and ‘elitist’. Yup. Great idea.

If you Non BGLO members would focus your time and energy on what YOU are doing for your community, we could have more positive articles.

So, because an individual reached high class and is now successful through hard work, generational wealth, and etc, they should be removed from the organization. That defeats the main purpose of these organizations, which is to help alleviate problems concerning young men and women to help improve their social status. People want don’t want to stay in low class forever.

Dr. Chambers,

I am not a member of a BGLO but I am a Howard Grad and a member of a black fraternal organization (Prince Hall Freemasonry).while I don’t totally agree with your critique, I would sum up my thoughts to be:”Even a broken clock is right twice a day”. Meaning that there is truth in what you’ve said, at least somewhat. What you’ve written as I see it, even if some of it is opinion or flat out wrong. From my recollection as a child I didn’t really see BGLO members do anything in my neighborhood which was in the poor areas of Newark, NJ and the surrounding area until I got ready to go to college. Thankfully a local Omega chapter gave me some scholarship funds to go to Howard (though I never aspired to join their organization). That said, it doesn’t mean they weren’t doing anything, but I do think they cater to the upwardly mobile. Is that wrong? Not necessarily, but if I’m right, such behavior is not above critique either.

I felt this article was rather disingenuous, especially the reference to WEB DuBois who actually was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha.

The speech quoted was not about black Greek organizations and how they were harmful and DuBois did not condemn them in that speech. The speech was about the need of black college students to not be like white college students – believing that college should be “fun” and students should not be engaged in frivolous activities like white students were who played athletics and who were members of their own Greek societies.

Black college students, he mentioned in that speech, should be working hard to solve the problems of our demographic. Our organizations – like BGLOs should also be working hard as a cultural institution of black America to solve our problems as demographic. By many measures BGLOs are nothing like their white counterparts. Our organizations have many more lifetime members, and as the author noted they are also dedicated to providing community service and scholarships to black communities/students.

I felt many of the items mentioned in this piece are rather outdated for BGLOs especially the relation to “colorism” as these organizations today, and even when I was in college at an HBCU over 20 years ago – they did not have only light skinned members, most of us were not from wealthy/bourgeoisie backgrounds, etc.

I’ll note I decided not to join a BGLO but many of my former classmates and family members are and they run the gamut of economic backgrounds and skin colors.

I think it is important for us not to put our black historical leaders in a specific box. DuBois did not blatantly criticize the existence of BGLOs and this piece doesn’t really speak on what the writer sees/defines “black culture” to be.

I agree with many aspects of this piece at it relates to white supremacy and the desire of many black people to prove they are “different’ and “better” than other black people – I agree that this is a symptom of blacks buying into the idea of our own inferiority. However, this is something that spans the demographic and is not specific to BGLOs. Personally, I feel this inferiority complex is our biggest issue as black Americans and that we do need to focus on our historical cultural attributes – our black American cultural attributes that have an historic basis from the 1700s forward. That cultural history does include forming our own organizations, churches, and fraternal organizations. They may seem to mirror more white organizations but once you look at their activities/traditions, they are very different and this is e specially the case for BGLOs.

I enjoyed the piece though and will check out the book.

After doing a system analysis of our people in America it would be better to do a 10 year transition from Black Greek organizations to African (scripted) organizations, to phase out the Greek connection. The mission and vision of the Black (Greek) organizations can remain the same but eventually take on a more fitting name – African.

There are so many ancient African scripts, thousands of years older than Greek, which itself finds it’s roots in ancient African scripts. Tifinagh, Osmanya, Nsibidi (this is where the Black Panther script was derived from), Meroitic and Proto-Saharan are just a few beautiful scripts that we could transition.

We have such a rich and diverse culture that has been hidden and largely forgotten. Who shall revive our knowledge of self and the work of our ancestors, unless WE DO IT OURSELVES.

Please Black Greek organizations, keep doing your wonderful work in our communities but let us step back and realize that we can do better to set our foundation in our own wonderful culture with our own remarkable scripts.

Nope, nope and nope. Article is so off-base. I would give it credit but it lacks honesty on so many levels.

If you are on the outside looking in, you have no clue. Your are making assumptions based on “surface” culture. And you are mistaken “why” these organizations were founded and it had nothing to do with assimilating within white culture in the early 1900’s…lol.

In total, this is a disingenuous look at BGLO life and culture. If you are not a part or don’t understand it, you really are in no position to criticize.

Do your research…find out the contributions of BGLO orgs and WHERE they were established and WHY. Do your research to find the 100’s of BGLO members who have impacted society in various ways…leading in the sciences, politics, education, entertainment, sports, etc.

If you are a member of a BGLO, I wonder where you get your information. If you are young in a BGLO, you need to give it some more time and become more aware of BGLO history before writing a condemning article..

Rest in Peace Dr. Chambers you are missed

How do you uplift a community and community economic development is not mentioned in your missions? In fact find me any historical black organization (church, Urban League, NAACP etc) that specifically states that community economic development and community wealth-building is a primary focus of their mission and purpose. I’m waiting

This can be said of just about “black” anything. Hence the rise and fall of Civil Rights. The problem is NOT BGLO’s, but Black People. Many often criticize what they don’t understand or more importantly what has been extorted and distorted into something completely contrary to the principles of its founders. I would agree that CURRENT BGLO’s have issues, but those issue come not from the organization, but from the assimilation of people with issues into the organization. Exclusivity is not the same as exclusion. The issues of self loathing, elitism, color selectivity, superiority are psychological and social issues that individuals have brought into the organizations and they have been erroneously branded as stereotypes onto the organizations. For every “is” there is an “isn’t”, but preconceived judgements won’t allow for the isn’t. People are fickle and find themselves more loyal to people than principles. Look at your president and the constitution. People would rather hold allegiance to him than the founding principles of a document that was set to cohesively bond. That is the fallacy of human nature and as you can see is not limited to a culture or demographic.

NOBODY knows the reason someone may join a sorority or fraternity but we all signed ourselves over to allegiance to founding principles that look nothing like what you see today in some chapters. It is hard to not fall prey to the stereotypical lure of the shallow representation that organizations present today, but some do manage it by holding true to their founding principles with pride. The things that would vindicate BGLO’s from these judgements are the very things that we pledge in secrecy, so more often than not there is no viable defense, especially when the “is” looks as bad as it does sometimes.

You will never please everyone and many times we must consider the source. God is no respecter of persons, so neither should we be. These continued jabs at organizations that are rooted in and founded on the very principles that they are judged for not representing is ludicrous. I would dare to say that the individuals within these organizations who fit these judgements would fit them with or without a Greek Letter behind their name, so its not the system but the people in the system.

To simplify this in basic terms, I would have to rely on an urban colloquialism and reverse it. “Hate the player, not the game.”

Please note that the author of this article, Professor Ali Chambers, sadly passed away earlier this year. With this in mind, comments on this article are now closed.

– Chris, LSE USAPP Managing Editor