Are state unemployment benefits a safety net or a hammock for the lazy? In new research, Thomas Biegert explores the effects of benefits on job seekers in 20 European countries and the US. He finds that in some countries, generous benefits are linked with high unemployment rates, while in others, the opposite is the case. This difference, he writes, may be related to the setup of a country’s labor market; people are willing to work despite generous benefits if there are good job opportunities.

Are state unemployment benefits a safety net or a hammock for the lazy? In new research, Thomas Biegert explores the effects of benefits on job seekers in 20 European countries and the US. He finds that in some countries, generous benefits are linked with high unemployment rates, while in others, the opposite is the case. This difference, he writes, may be related to the setup of a country’s labor market; people are willing to work despite generous benefits if there are good job opportunities.

It is a commonplace in much research but also the media and the general public that a generous safety net provided by the welfare state to those without work is quickly turned into a hammock for the lazy. The underlying claim is that people will not actively look for a job if the state provides them with a sufficient income.

The notion that benefits for the unemployed eventually lead to higher unemployment has justified welfare state retrenchment in many countries over the past decades. In the United States, for instance, benefits cuts and the introduction of an earned income tax credit were deemed to have been a success as they were seemingly associated with an increase in single mothers’ employment during the late 1980s and early 1990s. More recently, the Emergency Unemployment Compensation program, which in 2008 extended the period of potential unemployment benefits to buffer income loss in the economic crisis, was discontinued in 2013 based on the same reasoning. As Senator Jon Kyl of Arizona put it, generous unemployment insurance “doesn’t create new jobs. In fact, if anything, continuing to pay people unemployment compensation is a disincentive for them to seek new work”.

Yet, digging a little deeper, the relationship between benefit generosity and unemployment is much less clear-cut than suggested. We might ask the – maybe naïve – question: If it was true that receiving generous benefits from the state keeps unemployed people from looking for a job, why does a country with generous benefits such as Denmark not have dramatically higher unemployment levels than a country with stingy benefits such as the United Sates? The answer, as some research suggests, is that rather than only providing disincentives to work, benefits can also help unemployed people find a better job. This happens in two ways. First, having a financial buffer for themselves and their families enables jobseekers to wait for a job offer that matches their skills and requirements instead of having to take the first offer that comes their way. Eventually that means that jobs and employees have a better fit, which reduces the likelihood of quick employee turnover. Second, benefits provide jobseekers with the time and means to invest in their human capital. This increases their skill level and their employability which again will enable them to find a good job that they can and will keep for a longer time. Through these mechanisms, the safety net of the welfare state thus can be seen to work as a trampoline rather than a hammock.

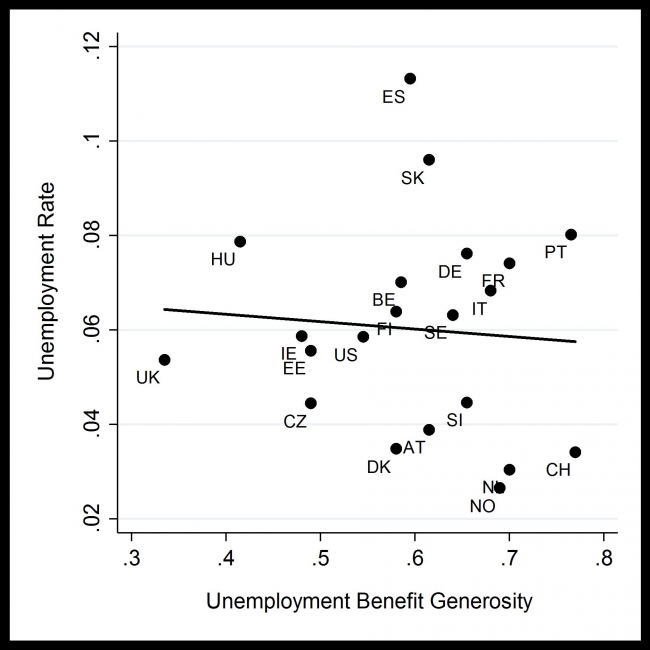

The question is under which conditions we can expect generous benefits not only not to harm but even boost employment. As can be seen in Figure 1, in 2008 there was wide variation in the association between generous benefits and unemployment rates. In some countries such as Germany, Portugal, Spain, or Slovakia comparative generosity seems to come with high unemployment levels. In others, such as Switzerland, Norway, the Netherlands, Denmark, the opposite is the case.

Figure 1 – Unemployment Benefit Generosity and Unemployment Rates in 20 European Countries and the United States in 2008

Note: Unemployment benefit generosity is measured as net replacement rates, which indicates the average amount a worker can receive from unemployment benefits expressed as a percentage of their former income.

In new research, I analyzed 20 European countries and the United States between 1992 and 2009 to demonstrate that whether generous benefits help job seekers find better jobs or whether they create an incentive to stay at home strongly depends on the availability of said better jobs. Their availability is determined by the institutional context of the labor market. More specifically, it depends on the chasm between those in good jobs – so-called insiders – and those in precarious jobs or unemployment – so-called outsiders. If the insiders’ positions are strongly protected by employment protection legislation and the wage bargaining process is set up so that unions mostly fight on their behalf while those at the fringes of the labor market are left out, employers will be more hesitant to offer these good jobs to outsiders. Rather they will offer them less protected and worse paid jobs at the labor market margins. In such a situation, only stingy benefits will force the unemployed take up these jobs. By contrast, when all jobs enjoy similar protection and wage bargaining outcomes take into consideration the whole economy, there will be more attractive job opportunities and generous benefits can work their magic and improve job to worker matches.

An example of this is the development of German unemployment support. The German government famously tightened welfare benefits in the so-called Hartz reforms in the early 2000s in order to increase incentives to work. At first sight, this strategy worked very well as Germany saw a drop in unemployment that even persisted through the economic crisis. In line with my argument, however, this is not at all surprising because Germany has a strongly segmented labor market and thus needs to force jobseekers to take less attractive jobs. No wonder that there has been a noticeable rise in atypical jobs in Germany, most prominently in fixed-term contracts and so-called mini-jobs (jobs with low working hours, low wages, and no benefits).

“Unemployment Office” by Bytemarks is licensed under CC BY 2.0

By contrast, Denmark is prominent for its “flexicurity” strategy that combines generous benefits with a labor market that does not create a strong divide between insiders and outsiders. Despite moderate welfare cuts, Denmark is able to maintain consistently high levels of employment and job quality.

The fact that cuts to welfare spending were associated with lower unemployment in the United States in the early 2000s does not fit this narrative. Especially, because the American labor market, too, does not create a deep divide between insiders and outsiders. On the other hand, the cross-national comparison indicates that the decrease in unemployment might have been due to other factors coming into play and that generous benefits would not have hurt this development. Similarly, the quick recovery in US unemployment after the economic crisis was aided rather than hindered by the temporary increase in the generosity of the Emergency Unemployment Compensation measure.

Returning to the question whether the welfare state’s safety net is a hammock or a trampoline, the answer is that this depends on the poles from which the net is spanned – the poles representing the setup of the labor market. People are willing to work despite generous benefits if there are good job opportunities. That means it is possible to achieve low unemployment while at the same providing high levels of social security for periods of unemployment. There are ways to combine high levels of economic security with better working conditions and income equality, without excluding sections of the population from gainful employment.

- This article is based on the paper “Welfare Benefits and Unemployment in Affluent Democracies: The Moderating Role of the Institutional Insider/Outsider Divide” in American Sociological Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2fIUQqo

_________________________________

About the author

Thomas Biegert – LSE Social Policy

Thomas Biegert – LSE Social Policy

Thomas Biegert is a Fellow in Social Policy at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He studies social inequality and stratification, labor markets, and welfare states, with a strong interest in quantitative methods. Other work on insiders and outsiders on the labor market authored by him has been published in Journal of European Social Policy and is Socio-Economic Review.