A key aim of public policymaking is to change public behavior in one way or another. In new research which focuses on voting patterns in Colorado, Andrew Menger and Robert M. Stein tested a number of ways of encouraging people to return their mail-in ballots early. They find that only message which increased early voting was one which explained that it had been introduced as a response to citizens’ demands. With this in mind, they argue that when public officials are trying to “nudge” public behavior, messages centered on how government is responding to the people can be useful for influencing how the public acts.

A key aim of public policymaking is to change public behavior in one way or another. In new research which focuses on voting patterns in Colorado, Andrew Menger and Robert M. Stein tested a number of ways of encouraging people to return their mail-in ballots early. They find that only message which increased early voting was one which explained that it had been introduced as a response to citizens’ demands. With this in mind, they argue that when public officials are trying to “nudge” public behavior, messages centered on how government is responding to the people can be useful for influencing how the public acts.

In new research, we demonstrate that a “responsiveness” message from election officials can affect voters’ method of balloting. Although our finding specifically concerns voting behavior, we believe that messages emphasizing how government is responding to citizens’ demands can be effective at nudging public behavior in a variety of settings.

In Colorado, which adopted universal vote-by-mail elections in 2013, election administrators found many voters returned their ballots close to or on Election Day. Since ballots needed to be verified and counted by the end of Election Day, these later ballot returns created a last minute rush of counting ballots, adding to the personnel costs and stress levels of administrators. In El Paso County, election officials sought to encourage the timely return of ballots through messages aimed at increasing early ballot return and in-person ballot drop-off (to avoid postal delays). We worked with the El Paso County Clerk’s office in the 2015 coordinated elections to examine the effects of different messages on voters’ timing and method of ballot return.

We developed the messages together with the County Clerk’s office and tested some of their ideas as well as ours. Using the registered voter file for the county, we randomized all the active registered voters by household into five treatment groups. We delivered the messages by inserting a sheet of paper containing the text into the official mailed ballot packet sent to each voter. The control message contained informational text that simply described how to return the completed ballot. The remaining – what we called the “treatment” – messages included the control text, but also inserted an additional paragraph with the treatment text.

“I Voted (Early)” by ep_jhu is licensed under CC BY NC 2.0

We tested two messages intended to increase early ballot return. The first message was called “stop the calls” and included this text:

If you are like many voters in El Paso County you may receive numerous calls, mailings, and other communications from campaigns. By returning your ballot early, campaigns will see that you have already voted and will have no reason to contact you. Help stop the calls by returning your ballot as soon as you have marked your choices!

The next message was called “voter confidence” and included these sentences:

You can help ensure that election results are reported as early as possible on Election Day by returning your ballot as soon as you have marked your choices. By returning your ballot early, you can be confident that your vote will be included when the first unofficial election results are announced.

We also tested two messages intended to increase the proportion of ballots returned in-person. The first message, intended to test the importance of voting together with other people, was called “social benefits” and included this text:

For some people, mailing off a completed ballot doesn’t give them the same voting experience as casting a ballot in person with other people. However, many voters find that dropping off their completed ballot provides a similar experience of traveling to a Voter Service and Polling Center, with the added convenience of filling out their ballot at home.

The final message was inspired by a previous study that found a message stating that early voting was adopted in response to citizen demand increased voters’ use of early voting. This message, which we termed “responsiveness,” included this paragraph:

An increasing number of El Paso County voters prefer to return their ballot in person rather than mailing their ballot to our office. In response to changing voter demand we have increased the number of convenient 24 hour secure ballot drop-off locations which are listed on the enclosed secrecy sleeve.

Following the 2015 local and coordinated elections, we examined the voter history file to observe whether voters cast their ballots early (which we defined as more than four days prior to Election Day) and in-person vs. by mail. These became the dependent variables in our analysis, which used logistic models with clustering by household to statistically estimate the effects of the treatment messages.

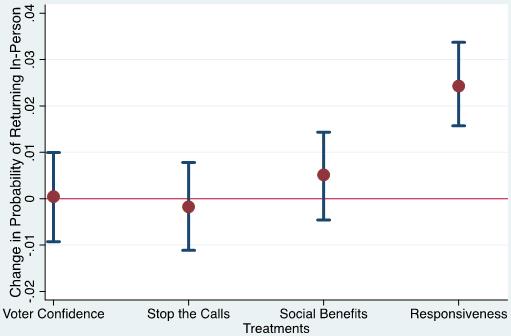

Figure 1 shows the effects of the messages on in-person ballot return. The only treatment that showed a statistically and substantively significant effect on in-person return was the responsiveness message. Telling voters that more in-person drop-boxes were added in response to their preferences caused them to be 2.4 percent more likely to return their ballots in-person.

Figure 1 – Effects of messages on in-person ballot return

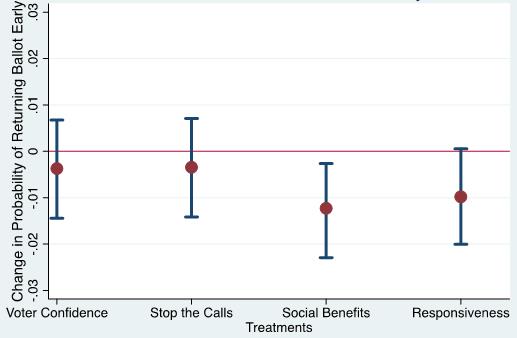

Figure 2 shows the effects of the messages on early return of ballots. The two messages we predicted to increase early ballot return had no discernable effect. Surprisingly, the messages aimed at increasing in-person balloting had the unexpected effect of decreasing early return! Both the social benefits and the responsiveness treatments decreased the proportion of ballots returned early, by 1.2 and 1 percent respectively.

Figure 2 – Effects of messages on early return of ballots

This experiment showed that a message emphasizing how policy changes were made in response to citizen demand can sway some voters’ method of balloting. We also found that increasing in-person return proved counter to the ultimate goal of increasing early balloting. Although the effect we observed was relatively small, we attribute this to the election setting and the experimental context. The electorate in local elections is predominately composed of frequent voters who have stronger habits of voting methods and may be less susceptible to messaging. Our effect was also limited because we did not send the messages across multiple media and at multiple times. We expect administrators who combine mailed messages with TV or newspaper ads should see a larger effect from a responsiveness message.

We think the results from this experiment are generalizable to the larger public administration and policy community. In any area where public officials are trying to “nudge” public behavior, messages centered on how government is responding to the people can be useful for influencing how the public acts.

Finally, we believe this project is a good example of how academics can work with public officials to provide scientific analysis of their public outreach strategies. These academic-practitioner partnerships can benefit both groups by providing important data to the researchers and answering practical questions for administrators.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Enlisting the Public in Facilitating Election Administration: A Field Experiment’, in Public Administration Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics, nor the authors’ institutions.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2Abrpca

_________________________________

About the authors

Andrew Menger – Rice University

Andrew Menger – Rice University

Andrew Menger is a Ph.D. candidate at Rice University, where he conducts research on the effects that election laws and administration have on political participation and voter behavior. He has several forthcoming publications on election administration as well as statistical methods used in Political Science. He expects to complete his dissertation on voting laws and the costs of voting in April 2018.

Robert M. Stein – Rice University

Robert M. Stein – Rice University

Robert M. Stein is Lena Gohlman Fox Professor of Political Science at Rice University, faculty director of the Center for Civic Engagement, fellow in Urban Politics at the Baker Institute, and former dean of the School of Social Sciences (1996–2006). His research focuses on election sciences, public policy, and public opinion. His research has been supported by the National Science Foundation, Pew Charitable Trusts, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, and Kinder Foundation.