While the American political party system seems entrenched at the national level, can other parts of government escape it? In order to encourage elected officials to pursue policies in the public, rather than partisan, interest, some local governments have adopted non-partisan elections. In new research, Craig Burnett, examines the partisanship of votes made by nonpartisan lawmakers in San Diego’s city council. He finds that, despite non-partisan elections, partisanship is still the strongest predictor of voting behavior.

While the American political party system seems entrenched at the national level, can other parts of government escape it? In order to encourage elected officials to pursue policies in the public, rather than partisan, interest, some local governments have adopted non-partisan elections. In new research, Craig Burnett, examines the partisanship of votes made by nonpartisan lawmakers in San Diego’s city council. He finds that, despite non-partisan elections, partisanship is still the strongest predictor of voting behavior.

Fed up with party bosses and machine-style politics, Progressive reformers of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries argued that a batch of reforms would break the grip of entrenched political parties. One of their primary goals was to minimize partisanship in elections. Nonpartisan elections seemed to be a natural way to achieve that goal: without an overt partisan affiliation, the political machine would break down. Instead of mindlessly voting for partisan candidates beholden to the parties who endorsed them, voters would evaluate party-free candidates based on their merits. The lack of a party label, in turn, would empower elected officials to pursue policy in the public interest, rather than their respective party’s interests. In new research, I found that the impact of nonpartisan elections is far from the Progressive’s ideal outcome. Party still matters and legislators vote precisely how we would predict based on their partisan affiliation.

There are good reasons to expect that nonpartisan elections would not achieve this Progressive reformers’ goal. After all, nonpartisan-elected city councilors are still members of a political party — the law simply prohibits them from broadcasting this affiliation on the ballot. Using roll-call voting data from San Diego’s City Council, I examined the voting behavior of city councilors. I found that party coalitions are still an important part of the legislative process, despite the fact that San Diego uses nonpartisan elections.

“IMG_4028-1” by Bengt Nyman is licensed under CC BY 2.0

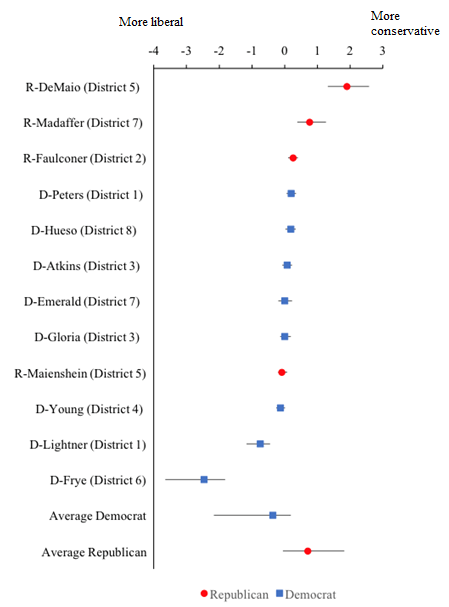

Using a statistical procedure to determine how liberal or how conservative an individual lawmaker is with respect to other members on the council (their ‘ideal point’), I analyzed 346 contested votes on the San Diego City Council from 2008-2009. With these estimates, I can place each councilor on a single scale to examine where each member falls relative to each other. Congressional scholars — who developed these tools — have been using this method to analyze voting behavior in both houses for quite some time, though my application is the first to look at a city council.

My analysis shows that partisanship is still the strongest predictor of voting behavior on a city council, even though the members compete in nonpartisan elections. Consider Figure 1, which maps the ideal points (and credible intervals of those estimates) of each legislator on the council from 2008-2009. With the exception of one legislator (Brian Maienschein, who has a longer backstory that his ideal point does not capture), there is a clear divide between Democratic and Republican members on the council. Put another way, if one were trying to explain the voting behavior of legislators on a nonpartisan-elected city council, one could do no better than to use the partisanship of those elected officials.

Figure 1 – Ideal Point Estimates of Legislators on the San Diego City Council, 2008-2009

While finding that partisanship matters in legislative voting is hardly new, finding that it matters in a nonpartisan environment at the local level is novel, and has important implications. These implications are either good news or bad news, depending on your perspective. This result is good news if you are worried that local elections do not garner the requisite attention from voters to cast an informed enough vote in nonpartisan elections ensure adequate representation. That is, if local elected officials mimic what happens at the national level — an arena that voters follow at least somewhat more closely — then this is probably good for local democracy. By contrast, this result is bad news if you are a reform-minded individual who would prefer that party politics has little or no impact on policymaking. At the least, nonpartisan elections do not seem to achieve that goal.

Extricating party from politics is a nearly impossible proposition in American politics, even at the local level. This is especially true in San Diego, which uses district-based elections. Given the continued level of political segregation across the United States — a phenomenon that we can observe at the local level — districts often produce ideologically minded representatives who are going to vote on legislative matters in a partisan way. Gerrymandering and polarization up and down the electoral system in the United States only contributes to this outcome. Additionally, political parties remain an important force in helping get their members elected, even in nonpartisan contests. Parties retain the ability to endorse candidates and campaign on their behalf. While nonpartisan elections can weaken the connection between elected officials and political parties, it is naïve to assume this reform can break the connection completely.

Finally, my analysis increases our scholarly understanding of what happens in local legislatures. The old scholarly canon argues that parties had a limited impact on politics. Prominent researchers have argued that local legislatures did little legislating of substance. My research paints a different picture of politics at the local level: Parties are an important force in shaping policy, even when the elections are nonpartisan. Along with other scholars researching in this area, the emerging literature in urban politics paints a picture of local democracy that establishes not only a clear electoral connection between voters and their representatives, but a government that is responsive to citizens’ preferences.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Parties as an organizational force on nonpartisan city councils’, in Party Politics.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2nnPjwf

_________________________________

About the author

Craig M. Burnett – Hofstra University

Craig M. Burnett – Hofstra University

Craig M. Burnett is assistant professor of political science at Hofstra University. His research focuses on state and local politics, urban politics, direct democracy, and electoral institutions. His recent publications have appeared in the Journal of Politics, Political Communication, and Electoral Studies.

1 Comments