On February 1st, the US District Court for the Northern District of Florida ruled that the state’s process of vote-restoration for those convicted of a felony violated the US Constitution. Sarah Shannon and Christopher Uggen write that Florida is one of the few states which still prevent felons from voting after they have completed their sentences. And while this ruling may signal that change is coming for those in the Sunshine State who are seeking re-enfranchisement, they remind us that restoring felon voting rights beyond Florida would give voting rights back to millions as well as enhancing public safety and community cooperation.

On February 1st, the US District Court for the Northern District of Florida ruled that the state’s process of vote-restoration for those convicted of a felony violated the US Constitution. Sarah Shannon and Christopher Uggen write that Florida is one of the few states which still prevent felons from voting after they have completed their sentences. And while this ruling may signal that change is coming for those in the Sunshine State who are seeking re-enfranchisement, they remind us that restoring felon voting rights beyond Florida would give voting rights back to millions as well as enhancing public safety and community cooperation.

Florida’s felon disenfranchisement laws are among the strictest in the nation, barring people with felony convictions from voting even after they have completed their sentences. On February 1, the US District Court for Florida’s Northern District ruled that the state’s process of vote-restoration for people with felony convictions is “crushingly restrictive,” arbitrary, and discriminatory in ways that violate the US Constitution’s First and Fourteenth Amendments. In the court’s summary judgement, Judge Mark E. Walker stated, “If any one of these citizens wishes to earn back their fundamental right to vote, they must plod through a gauntlet of constitutionally infirm hurdles. No more.”

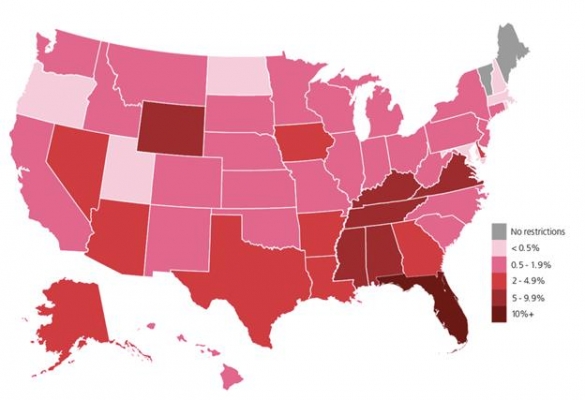

The court’s ruling cites our 2016 Sentencing Project study of felon disenfranchisement across the nation. We estimated that more than 6 million US citizens were barred from voting in the 2016 election because of a felony conviction. As Figure 1 shows, in Florida, this means that 10 percent of all people of voting age and more than 20 percent of voting-age African Americans cannot vote. Florida accounts for 27 percent of all people disenfranchised for felony convictions nationally. These numbers are so high in Florida because it is one of the few remaining states that bar voting after people have served their time, so that people convicted decades ago could remain disenfranchised for the rest of their lives. The 1.5 million people disenfranchised post-sentence in Florida account for nearly half (48 percent) of all people disenfranchised in the 12 states that have such restrictions.

Figure 1 – Total felon disenfranchisement rates, 2016

The district court’s ruling certainly signals new hope to Floridians seeking rights restoration after completion of their sentence. Florida is well known for its restrictive and slow rights restoration process. The state re-enfranchised 271,982 people between 1990 and 2015, but most occurred during Governor Charlie Crist’s administration (2007-2011), which took bold steps to streamline the process. Current Governor Rick Scott ended these reforms after taking office and fewer than 2,000 Floridians had their voting rights restored between 2010 and 2015.

In spite of this recent good news for many of Florida’s disenfranchised citizens, it’s important to note that it applies only to Florida’s method of re-enfranchisement; it does not impact the state’s disenfranchisement law itself, which has previously been deemed to be constitutional. The ruling also upholds as constitutional the state’s five or seven year waiting period (depending on the offense type) for applying to have rights restored after completion of sentence. The court did not specify a new method for re-enfranchising Floridians with felony convictions, but has set a deadline for the state and the plaintiffs to present solutions to the court. It’s not clear yet what the remedy will be.

But the court’s ruling isn’t the only sign that change is afoot for felony disenfranchisement in Florida. In November, Florida voters will consider a constitutional amendment called, “The Voting Rights Restoration for Felons Initiative” or Amendment Four. A recent poll conducted by the University of North Florida found that 71 percent of registered voters in Florida planned to vote “yes” in favor of restoration of voting rights at the completion of a felony sentence. Spearheaded by Floridians for a Fair Democracy, advocates gathered more than 700,000 petition signatures to include the amendment on November’s ballot. If the initiative passes, Floridians who complete their full sentences and were not convicted of select offenses (murder, felony sexual offense) will be eligible to vote.

“3812660365” by Neil Conway is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Successful passage of Amendment Four would bring Florida in line with 18 other states that disenfranchise people only for the duration of their sentence. It would also reflect the opinion of a significant majority of Americans who support restoring voting rights for people with past felony convictions. In fact, over 60 percent of Americans would go further and support re-enfranchisement of people who are currently on probation or parole. In much of the world, prisoners retain the franchise and debates in law and policy generally concern whether currently incarcerated citizens may vote. In contrast, 48 of the 50 US states do not allow prisoners to vote.

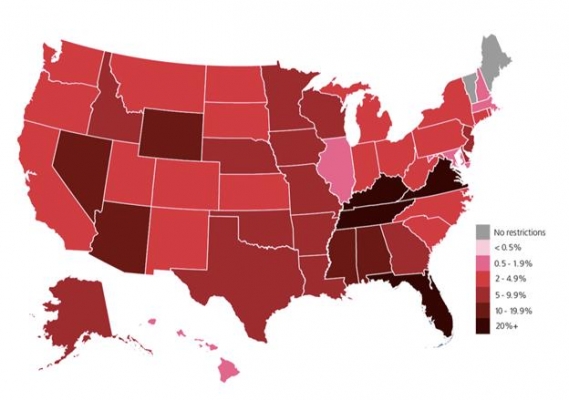

The benefits of restoring voting rights to citizens who have served their time could be far-reaching and include decreasing racial disparities, enhancing public safety, and extending democracy. The racial disparities in felon disenfranchisement are substantial nationwide (7.4 percent of voting-age African Americans vs. 1.8 percent of non-African Americans). Nearly 40 percent of the 1 million African Americans disenfranchised after the end of their sentence in the United States live in Florida (Figure 2). Research has established that felon disenfranchisement laws like that of Florida are rooted in the nation’s long history of racial animus. Extending the franchise to Floridians who have completed their sentences could go a long way toward lessening this historic burden on African American citizens and communities.

Figure 2 – African American felony disenfranchisement rates, 2016

What’s more, public safety could be enhanced, rather than undermined, by a swifter restoration of full citizenship to those who have served their time. Some research has indicated that voting promotes greater civic engagement and lower recidivism among people with former felony convictions. As we have shown, 77 percent of all those disfranchised in the United States are living, working, paying taxes, and otherwise getting by in their communities. Half of all those disenfranchised nationwide have completed their sentences, and half of this latter population lives in the state of Florida. Restoring the vote to these citizens would promote reintegration by offering people with felony convictions the chance to participate as full stakeholders in their communities.

To state it plainly, dismantling the arduous and arbitrary process for restoring voting rights in Florida – and beyond – is the right thing to do, as the US District Court of Florida’s Northern District has ruled. It is in line with good social science and will go a long way to empowering Florida’s citizens currently languishing on long waiting lists, eager to participate fully in their communities. Many Americans would support going further, restoring the franchise to those still serving their sentences in the community and even those in prisons. Florida, and other states, would do well to heed public opinion and end these discriminatory practices for the sake of democracy and public safety.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2ED5MAC

_________________________________

About the authors

Sarah Shannon – University of Georgia

Sarah Shannon – University of Georgia

Sarah Shannon is an Assistant Professor in Sociology at the University of Georgia. Her interdisciplinary research investigates how social institutions like the criminal justice and public welfare systems affect social inequality.

Christopher Uggen – University of Minnesota

Christopher Uggen – University of Minnesota

Christopher Uggen is Regents Professor and Martindale chair in Sociology, Law, and Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota. He studies crime, law, and social inequality, firm in the belief that good science can light the way to a more just and peaceful world.

If you aren’t willing to follow the law yourself, then you can’t demand a role in making the law for everyone else, which is what you do when you vote. The right to vote can be restored to felons, but it should be done carefully, on a case-by-case basis after a person has shown that he or she has really turned over a new leaf, not automatically on the day someone walks out of prison. After all, the unfortunate truth is that most people who walk out of prison will be walking back in. Read more about this issue here: http://www.heritage.org/crime-and-justice/report/felon-voting-and-unconstitutional-congressional-overreach