Election coverage often refers to a “gender gap”, meaning different vote choices between women and men. But such references are in fact talking about differences by sex. But does how we measure gender influence what we can say about people’s political preferences? In new research, Amanda Bittner and Elizabeth Goodyear-Grant used surveys to capture people’s subjective gender identity, and then examined respondents’ attitudes based on these reported identities. They find that not all women are the same, and neither are men: people’s idea of their own gender does not always fit with their sex, and their political attitudes are also based on where they consider themselves to be on the gender scale.

Election coverage often refers to a “gender gap”, meaning different vote choices between women and men. But such references are in fact talking about differences by sex. But does how we measure gender influence what we can say about people’s political preferences? In new research, Amanda Bittner and Elizabeth Goodyear-Grant used surveys to capture people’s subjective gender identity, and then examined respondents’ attitudes based on these reported identities. They find that not all women are the same, and neither are men: people’s idea of their own gender does not always fit with their sex, and their political attitudes are also based on where they consider themselves to be on the gender scale.

We often hear about the “gender gap” in reports about election outcomes and public opinion. The New York Times’ coverage of the most recent American presidential election results, for example, highlights the differences in vote choice by gender, referring to a “pink and blue America”, while the Washington Post referred to the election as “ the widest gender gap in recorded history”. What these articles are talking about is the difference in vote choice between women and men (sex), although they use references to masculinity and femininity (for example, blue and pink) to unpack the results (gender). Two things are problematic about this trend: first, we’re calling sex and gender the same thing, and they’re not the same. Sex is biological (it’s about what you find underneath your diaper), and gender is socially constructed. Second, we’re talking about gender differences, but we’re measuring gender as if it’s sex. Is gender really just two categories (male/female)? Or is gender something more complex, more fluid? What happens to our findings about gender and political attitudes if we measure gender differently?

For years, survey research has measured gender as if it’s sex, with just two categories. For a long time, while telephone surveys were the norm, we didn’t even ask respondents to identify their sex/gender. Rather, interviewers determined the sex/gender of the respondent by deciding whether their voice “sounded” masculine or feminine, checking a box on behalf of the person on the other end of the phone. With the advent of web surveys, this has changed somewhat, and now respondents can check their own boxes, but this is only if we set the survey up to let them. And it still doesn’t address the issue of whether or not the boxes actually reflect “real” gender and whether sex is a good proxy for gender.

By CCO Public Domain [CC BY-SA 4.0 ], via Wikimedia Commons

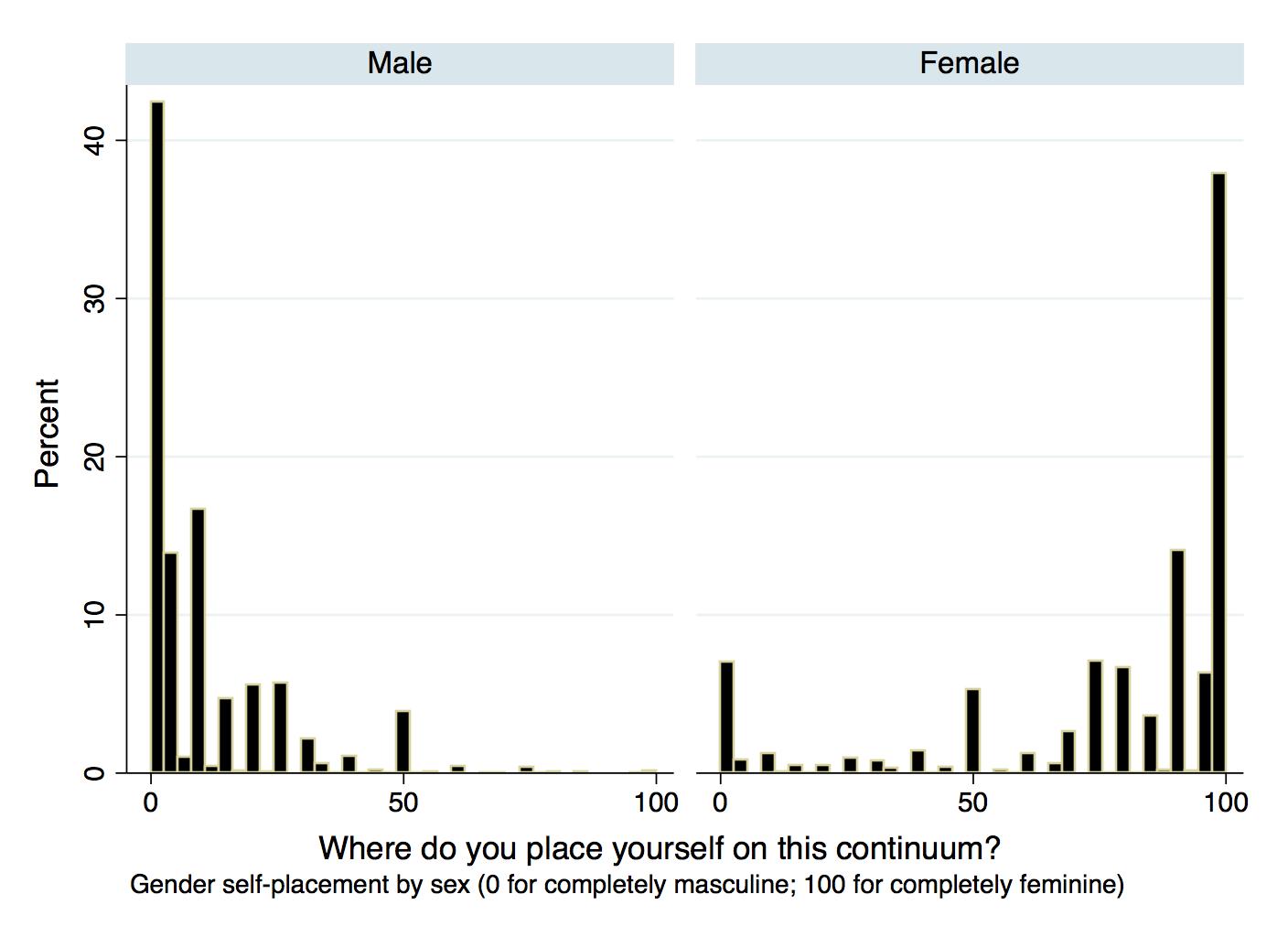

In a recent set of surveys, we gave respondents different options for the gender question. The “traditional” measure of sex was included (male/female), and in addition to that, we asked people to answer a non-traditional measure designed to capture subjective gender identity. We showed people a picture of a horizontal line with two end-points, and asked them to place themselves on a continuum of 100 percent masculine to 100 percent feminine, with the mid-point unlabelled. Not surprisingly, as Figure 1 shows, perceptions of masculinity and femininity mapped somewhat closely onto the traditional measure of sex (the two are closely tied, and our ideas about gender in society are based partly on our biology). However, about 30 percent of respondents did not place themselves close to the end-points. Furthermore, there were a number of people whose sex and gender did not “match” in the conventional sense. These were women who saw themselves on the masculine side of the continuum, and men who saw themselves on the feminine side of the continuum. In fact, fully 7 percent of the women we surveyed considered themselves 100 percent masculine, that is, they identified with gender normally associated with the opposite sex. These findings alone are enough to tell us that we need to rethink how we measure gender, since we’ve been consistently miscategorising a sizeable group of people.

Figure 1 – Gender self-placement, by sex

Relying on the two-category sex variable, traditional gender gaps research generally finds that women are more left-leaning than men. In practice, this means women are more liberal than men on state-funded social programs including education, healthcare, and welfare; on same-sex marriage, access to abortion, and other moral and lifestyle issues; and on women’s role in the workplace and politics.

What Happens when we Examine Attitudes by Gender instead of by Sex?

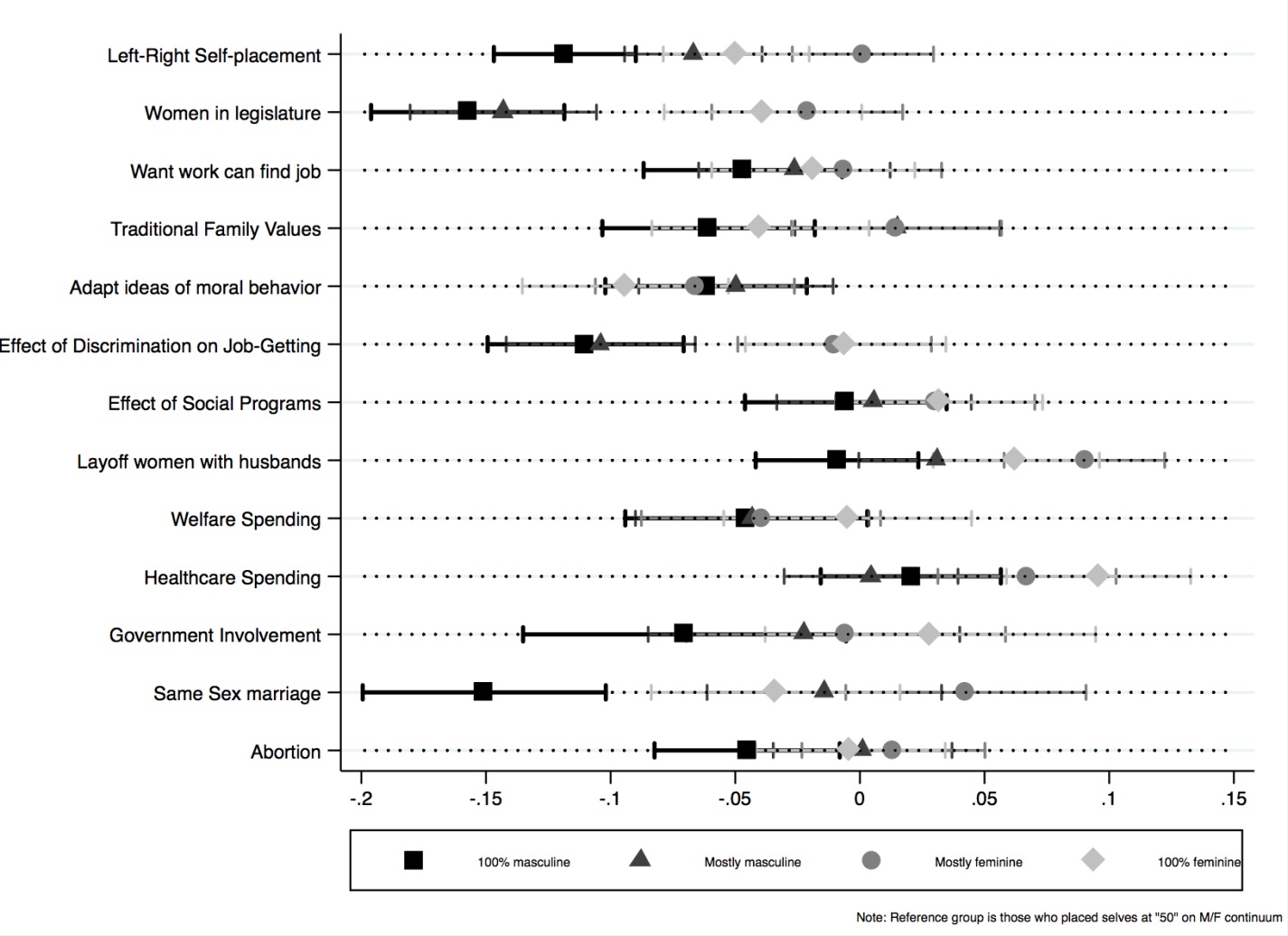

When we consider attitudes to these same issues through the lens of gender as we measured it, rather than comparing women to men, we get a more nuanced picture of the gender gap. We broke the 0-100 continuum down into five groups: those who considered themselves to be a) 100 percent masculine; b) those who placed themselves between 1 and 49 on the continuum (“mostly masculine”); c) those who placed themselves right in the middle (not labelled in the survey question); d) those who placed themselves on the feminine end but not at 100 percent feminine ( “mostly feminine”); and e) those who placed themselves at the end-point of femininity, at 100 percent feminine. We then compared attitudes across a bunch of questions where we know there are gaps across sexes – with women to the left of men. What we found was that there are substantial nuances in the gender gaps story.

Figure 2 – Effects of gender self-placement ‘‘categories’’ on issue attitudes and ideology

Figure 2 shows that those people who place themselves in the “mostly feminine” category are the most liberal on most issues. This group places itself furthest to the left when asked about its ideology, and is also most liberal on six of the other questions (and tied for most liberal on two additional questions). Those who think of themselves as 100 percent feminine are most liberal on only two issues – healthcare spending and the effects of government involvement in the state. This means that attitudes aren’t just based on whether or not you are a woman or a man. There are differences based on where you think of yourself in terms of gender.

On the masculine side of the scale, the “mostly masculine” are most left-leaning on one issue: they are more likely than other groups to believe we should adapt our ideas of moral behavior with the times. Those who think of themselves as 100 percent masculine are never the most left-leaning on any issue, but they are also not always the most conservative: those who see themselves as 100 percent feminine are least likely to support the idea that we ought to adapt our ideas of moral behavior with the times.

What does all of this mean?

We can draw a few conclusions from these results: first, gender and sex are not the same. Sure, they’re closely linked, but there is a non-trivial number of people who don’t fit the traditional boxes. Second, if we use a more nuanced measure of gender, we get a more nuanced picture of the impact of gender on attitudes. Not all women are the same, and neither are men. The traditional measure treats these groups as uniform, and as a result we are missing important information about the distribution of preferences in society. Finally, we aren’t sure our question is necessarily the right way to measure gender, ultimately. We’re in the midst of a larger project that analyzes how to measure gender in survey research, with the hope of finding the optimal measure for future use. In the meantime, though, these results are revealing, for they tell us that there is more to gender than sex, and if we want to understand political attitudes more fully, we should keep digging.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Sex isn’t Gender: Reforming Concepts and Measurements in the Study of Public Opinion’ in Political Behavior.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2oDKpJH

_________________________________

About the authors

Amanda Bittner – Memorial University

Amanda Bittner – Memorial University

Dr. Bittner is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science and the Director of the Gender and Politics Lab at Memorial University. Her research focuses on elections and voting in both Canadian and comparative contexts. In addition to her ongoing work on voters’ perceptions of party leaders, she has published research on parenthood and politics, voter turnout, as well as the impact of social cleavages and political sophistication on political attitudes.

Elizabeth Goodyear-Grant – Queen’s University

Elizabeth Goodyear-Grant – Queen’s University

Elizabeth Goodyear-Grant is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Studies at Queen’s University, and the Director of both the Queen’s Institute of Intergovernmental Relations (IIGR) as well as the Canadian Opinion Research Archive (CORA). Her research focuses on Canadian and comparative politics, with particular interests in electoral politics, voting behaviour, and public opinion; news media; and the political representation of women.