In the wake of the tragic shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida on February 14th, many of the school’s students have pushed hard for more stringent gun control legislation, only to be met with vitriolic attacks from the right, often accusing them of being ‘crisis actors’. Ben Margulies writes that the treatment of these students echoes the way whites treat non-white political opponents: often as ‘enemies’ or ‘aliens’ who are unworthy of civil discourse.

In the wake of the tragic shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida on February 14th, many of the school’s students have pushed hard for more stringent gun control legislation, only to be met with vitriolic attacks from the right, often accusing them of being ‘crisis actors’. Ben Margulies writes that the treatment of these students echoes the way whites treat non-white political opponents: often as ‘enemies’ or ‘aliens’ who are unworthy of civil discourse.

There is little new to say about the United States’ unique gun culture, or about the grievous impact that this culture has on public safety in the country. The February 14th attack at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida is, by one count, the eighth school shooting of 2018 (note that the list limits itself to shootings at schools). Seventeen died at Parkland, making the massacre only the third-deadliest school shooting in US history.

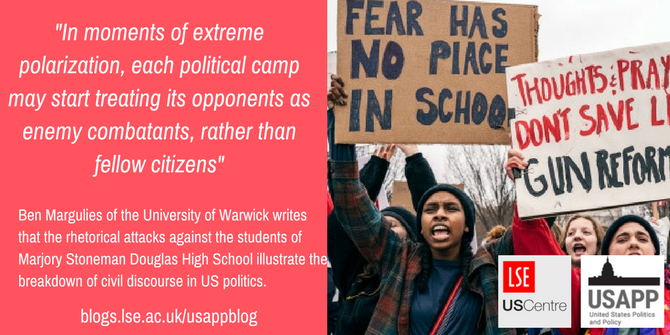

What is new – at least among white American students – is the wave of gun-control activism that has swept American schools, including Douglas itself. Students are demonstrating, striking and marching across the United States to demand new legislation restricting the sale of firearms, and the magazine capacities of those sold. Though the US has long had gun-control activists, this spontaneous expression of student activism is new to American gun politics.

What is sadly less unexpected is the disdain and hostility with which these students –often grieving students – have been met by some gun-rights supporters. Some conservative commentators have harshly denounced Douglas students’ lack of “civility” or due respect when they appeared at a public debate with one of Florida’s US senators, Marco Rubio. One Douglas student was accused of being a “plant” or of working for the (allegedly anti-Trump) FBI. Another Douglas student received death threats. Conspiracy theories circulate on the Internet, claiming that the students are in fact “crisis actors,” shuttled to massacre sites in order to attack the Second Amendment.

No one thinks paranoia or extremism are novel in American politics . However, it remains shocking to see such vitriol directed at teenagers, at those deemed to be, by the law and by social mores, as children. Even in a country as polarised as the United States, it is surprising to see adults attack children simply for taking the opposing side in a political dispute. What does it say about the current state of the American nation that we give children no quarter?

A survey of the prehistory of the “crisis actor” myth reveals one answer. The charge that activists pay for “victim” testimony or agitation has dogged civil-rights activists since the Reconstruction era – in short, it is a charge usually levelled at African-Americans and those who support their civil rights. American gun culture is intertwined with its racial politics. Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz argues that the right to bear arms is intimately connected to the seizure of Indian lands, while Stephanie McCurry notes in her Confederate Reckoning, the idea that white men have the right to determine when violence is appropriate was key to pre-Civil War Southern society. Michael Belleisles describes the post-Civil War South, where whites exercised private violence with impunity against African-Americans, and Republicans of both races; their immunity from prosecution was almost a mark of citizenship. The FBI long conducted illegal surveillance and infiltration operations within the Civil Rights Movement, and law enforcement services have been accused of using counter-terrorism assets to monitor Black Lives Matter. In this sense, African-Americans and American Indians were akin to colonized populations, and were not subject to normal laws.

“Thoughts and Prayers Don’t Save Lives, student lie-in at the White House to protest gun laws” by Lorie Shaull is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

The Douglas High activists are mainly white. However, race in the United States means more than just skin color. It is a marker of citizenship, of being a rights-bearing person, indeed a person in the fullest sense of the word. Being non-white has always been a marker of lesser personhood in American life. So to treat the Douglas High students with such venomous disregard, and view them through the same paranoid lens – to treat them almost as if they were not white – i.e., as many people of color have historically been treated in the US, suggests that, to some gun-rights activists, they too are not fully citizens somehow. They are enemies. Tellingly, some of the some conspiracy theories that entangle the new gun-control movement also smeared Black Lives Matter – both have been accused of receiving money from George Soros, for example.

In his Fire and Blood, Enzo Traverso, writing on Europe in the era of the World Wars, repeatedly returned to the theme of “civil war.” Specifically, he referred to the central quality of civil war that makes it so unusually violent and sanguinary. In a civil war, the two sides cease agreeing on a common code of rules, of conduct, of institutional functioning – “a breakdown in order within a state” where each group claims to have the monopoly on legitimate authority, and the other side are seditious (p.71). Rules cease to apply. Each side becomes either foreign, or traitorous – “the internal rebel of civil war, like the criminal or the indigenous rebel of colonial wars, is an outlaw with whom no compromise is possible”. Since civilians can commit treason at home (whereas they do not go to war against external foes), “the distinction between civilian and combatant becomes highly problematic.” Michael Ignatieff made the point more pithily: “An adversary is someone you want to defeat. An enemy is someone you have to destroy.”

The United States is by no means on the verge of (another) civil war. The battles fought across the American political landscape are rhetorical, not physical. Rather, Traverso’s writings, and the experience of American racial violence, serve more as an analogy for how polarization and breakdown can strip away the protections and respect we would normally accord to fellow citizens, especially those deemed worth of some special protection, like schoolchildren. To put it another way, in moments of extreme polarization, each political camp may start treating its opponents as enemy combatants, rather than fellow citizens, and in the United States, such treatment is likely to echo – however distantly – the way whites treat non-white political opponents.

The United States is an increasingly polarised country. A 2014 Pew Research report found a large minority of Democrats and Republicans considered the opposing party’s programmes “so misguided that they threaten the nation’s well-being.” The country has also experienced a growing disaccord about the proper functioning of its institutions. The Republican Party has increasingly adopted a majoritarian view of power that ill-suits the American constitutional model, producing gridlock. Republicans barely acknowledged the legitimacy of Barack Obama’s presidency. The judiciary is openly politicised, as is the process of legislative redistricting at federal and state levels. With the Trump administration, long-held conventions about presidential transparency have been abandoned.

Again, my point is not that the United States faces an imminent explosion of civil strife or violence, beyond that low-level violence being wreaked by its armed citizens. What it does face, however, is a growing tendency for groups on one side of the country’s cultural and social political divides to treat opponents as outside the normal bounds of the polity. They become aliens outside the protection of our social norms. The fact that this tendency now extends to teenagers, and that they have been stripped even of the protection normally afforded to the grieving, may not equate to civil war. But it is alarming – and very sad.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2H3vCPm

______________________

About the author

Ben Margulies – University of Warwick

Ben Margulies – University of Warwick

Ben Margulies is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Warwick.