In Black Skin, White Masks – first published in 1952 – Frantz Fanon offers a potent philosophical, clinical, literary and political analysis of the deep effects of racism and colonialism on the experiences, lives, minds and relationships of black people and people of colour. Leonardo Custódio reflects on the enduring relevance of Fanon’s classic work, here published in a new edition featuring an introduction by Paul Gilroy.

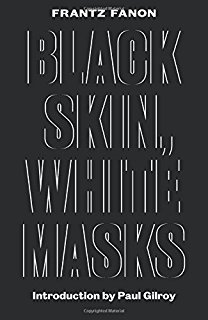

Black Skin, White Masks. Frantz Fanon. Pluto Press. 2017 [1952].

The Enduring Relevance of Black Skin, White Masks

Frantz Fanon’s classic Black Skin, White Masks is a book of enduring relevance. For that reason, this new edition from Pluto Press is definitely welcome. Fanon’s self-reflexive, philosophical, poetic, literary, arguably clinical and, above all, political analysis is still a powerhouse. It remains a fundamental part of the contemporary constellation of intellectual and activist struggles and discourses working to denounce and contest the effects of racism on the lives and minds of black people and people of colour.

My own ignorance – or ‘alienation’, in Fanon’s terms – fits as illustration of the continued resonance of Black Skin, White Masks. The first time I – a highly educated black man from a former colony living in predominantly white Finland – heard about Fanon’s work was in late 2016. At the time, I had written a response to black Brazilian feminist academics and activists who have extensively analysed the relationship between systemic racism and the solitude of black women in our country. In a blog post, I reflected about how I consciously and unconsciously reproduced racist patterns of behaviour as I grew into adulthood. In reaction to this, a Brazilian colleague asked me: ‘have you read Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks? You should.’

Her exigent tone made sense when I read one of the book’s previous editions. I was unaware that a book had theorised about the uncomfortable facts of racism I had experienced or reproduced as a privileged black individual in the deeply white-normative and racist Brazilian society. Despite being the largest African diaspora in the world, most things considered ‘normal’ and ‘positive’ in Brazil – including physical appearances, manners, music, religion, language, politics and other arenas of social relation and power – reflect the historical European colonialism and the contemporary hegemony of North American and Western European values attached to neoliberalism. In contexts like Brazil and other postcolonial societies, those who denounce racism tend to be seen as over-sensitive and radical. In many cases, people of colour learn from an early age that racism exists, but hard work, ‘proper’ education and ‘good’ behaviour are key to avoid suffering from it. Most importantly, people of colour also internalise and reproduce racist attitudes. In other words, the problems Fanon originally analysed in 1952 remain today, six decades later.

Image Credit: May Day 2015 (Nancy Sims CC BY 2.0)

Image Credit: May Day 2015 (Nancy Sims CC BY 2.0)

One of the highlights of the new edition of Black Skin, White Masks is Paul Gilroy’s introduction. Even though the experiences of people of colour in contexts of white predominance are still recognisable in the present moment, Fanon’s argumentation feels sometimes dense and difficult to navigate, particularly for those unfamiliar with scholarship in psychology, psychiatry and philosophy. In this sense, Gilroy’s introduction puts Fanon’s work in historical context and analyses how it resonates today. Gilroy also tackles some of the book’s argumentative, philosophical and even translation weaknesses to warn us about how ‘its rhetorical, poetic and surrealist elements should be read and interpreted with the greatest of care to retain the complexity and style of the original’ (x). Gilroy’s introduction, together with the previous forewords by Homi K. Bhabha (1986) and Ziauddin Sardar (2008) – also available in the new edition – help new general, academic and/or activist readers to Fanon’s first published book.

To reflect on the impacts of colonisation and whiteness on black people from the colonies (Fanon specifically focuses on the Antilles, where he is from), Black Skin, White Masks combines literary analysis, reflections on lived experiences and critical approaches to scholarly literature, especially from psychology and philosophy. In the first three chapters, Fanon examines how these impacts of colonisation can be observable in language and, controversially, in interracial relationships. I consider these chapters important because they problematise the internalisation and reproduction of whiteness among postcolonial black people. In Chapter Four, Fanon critically examines an essay by M. Mannoni to question the author’s idea that colonisation happened because of a sense of inferiority and even a pre-existing unconscious desire among black people to be colonised and dependent on white Europeans. In Chapter Five, Fanon shifts towards patterns of resistance to whiteness among black people who develop and embrace black consciousness. In Chapters Six and Seven, Fanon reflects on symbolic, material, interactional and sociopsychological factors to develop a ‘psychopathological and philosophical explanation of the state of being a Negro’ (6, emphasis in original). All in all, in addition to describing the book as a ‘quest for disalienation’ (192), Fanon concludes the book with a call for black and white people together to ‘turn their backs on the inhuman voices which were those of their respective ancestors in order that authentic communication is possible’ (199).

As a black man raised in a postcolonial society myself, reading Black Skin, White Masks has been an emotional and illuminating experience, especially because I realise how my own lifetime contradictions in a white world have for so long blinded me from even knowing about the book’s existence. For me, Fanon’s book remains a relevant companion to more recent work, such as those of black feminist writers like Angela Davis, bell hooks and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, to name but a few who write in English across a very diverse body of literature. In fact, it would be interesting to see how, if still alive, an older Fanon would react to those who identify sexism, especially towards black women (e.g. Bergner 1995), and homophobic tones (e.g. Moore-Gilbert 1996) in his first book. Impossible hypotheses aside, Fanon’s book has remained relevant because it provokes people of colour and white people to confront the powerful ways in which structural racism affects minds, relationships and everyday politics in a world that remains extremely unequal and violent in terms of racial relations.

- This review originally appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2GmF5EM

About the reviewer

Leonardo Custódio – University of Tampere, Finland

Leonardo Custódio is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Institute for Advanced Social Research (IASR) at the University of Tampere, Finland. He tweets @_LeoCustodio_ .

Find this book:

Find this book: