The rise of the Black Lives Matter movement following the 2014 shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, also focused attention on how police and city officials use fines taken from communities of color to fund city administration. In new research, which examined revenue data from more than 9,000 cities, Michael W. Sances and Hye Young You find that cities with a larger African American population collect a greater number of fines. They also find that the relationship between race and fines is much weaker in cities with Black representation on city councils.

The rise of the Black Lives Matter movement following the 2014 shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, also focused attention on how police and city officials use fines taken from communities of color to fund city administration. In new research, which examined revenue data from more than 9,000 cities, Michael W. Sances and Hye Young You find that cities with a larger African American population collect a greater number of fines. They also find that the relationship between race and fines is much weaker in cities with Black representation on city councils.

Do governments treat some citizens differently than others? Would achieving political representation benefit disadvantaged groups? These are classic questions of democratic representation, but they have a renewed urgency in the wake of recent accusations that local governments and local police, in particular, discriminate against their African American citizens.

These biases run much deeper than the violence of police shootings of civilians or racial discrimination by law enforcement agencies; indeed, those particular sensationalized episodes may reflect a general culture of unequal treatment at the local level. An important part of that culture is the reliance on criminal fines and fees as a source of revenue, which disproportionately affects minority residents.

Such was the conclusion of the Obama Administration’s Department of Justice (DOJ) investigation into the community of Ferguson, Missouri, in the wake of the Michael Brown shooting in 2014. This particular shooting, the DOJ concluded, was part of a broader pattern on the part of the majority-white city council and police, who openly targeted the majority-black population with fines to raise revenue to address a substantial sales tax shortfall. Fines are one of the few revenue sources over which local governments have considerable discretion. The DOJ report concluded that the reliance on using fines and fees to sustain the city’s budget deepened the mistrust toward law enforcement and municipal courts held by local residents in Ferguson.

While the Justice Department drew general conclusions from the case of Ferguson, and journalistic reports pointed to similar cases in other cities, we were curious as to how systematic the pattern of reliance on fines was. To explore this question, we examined revenue data from over 9,000 cities using the federal Census of Governments. In recent years, the Census of Governments has asked cities how much revenue they collect from “penalties imposed for violations of law; civil penalties (e.g., for violating court orders); [and] court fees.” We focused on these 9,000 cities as they had populations of at least 2,500 (the conventional definition of an urban area) and because they had a police force, a court system, or both.

“Ferguson Media Coverage-30” by Patrick Giblin is licensed under CC BY NC 2.0

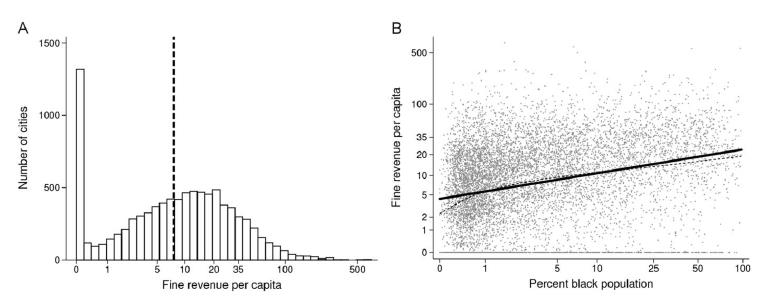

We first sought to answer two basic questions: How many cities rely on criminal fines for any revenue, and what do cities collect on average? We found that the use of fines is very common, with 86 percent collecting at least some revenue from fines. Of the cities that collect any fines for revenue, the average amount collected was $11 per city resident, but the range of fines across the cities we examined was anywhere from a few cents to a few hundred dollars per person.

Next, we investigated if cities collect more fines if the majority of a city’s residents are African American. To do so, we began by simply plotting the amount of fines revenue per capita against the percent of a city’s population that is black (both on a log scale). As shown in Figure 1 above, there is a strong positive relationship between the two. In cities with the smallest share of blacks, the amount of fines revenue per capita is less than five dollars; in cities with the most blacks, fines revenue is $24, on average. This relationship is robust to adjusting for local fiscal conditions, other demographics, and crime, leading us to conclude that the patterns of discrimination uncovered in Ferguson and other selected cities are indeed pervasive.

Figure 1- Fine revenue per capita and percent black population

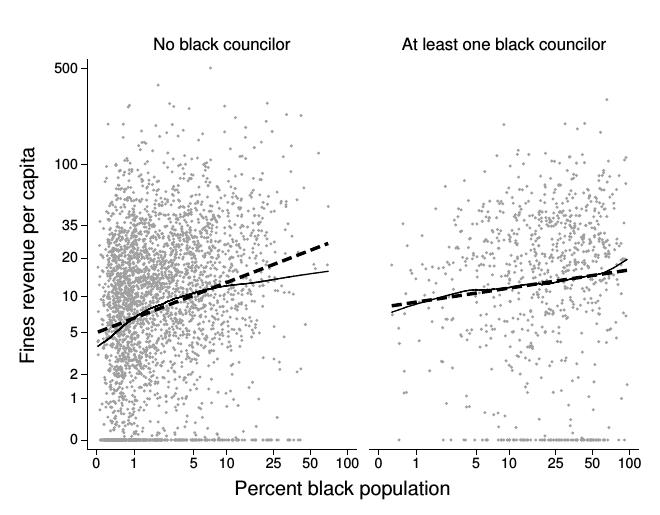

Finally, we wanted to know if achieving minority representation changed policy. To answer this question, we combined our fines data with information on black representation on city councils. We were able to obtain representation data for a little under 4,000 cities, and we use the presence of one or more black city councilors as our measure of descriptive representation. We then ask if the relationship between fines and the black population is diminished in cities with black representation.

As shown in Figure 2, the relationship between race and fines is much weaker in cities with at least one black councilor (right panel), and is stronger in cities with no black representative (left panel). The difference in these relationships is statistically significant, and the pattern is robust to adjusting for other variables and for measuring under-representation in alternative ways. Thus, it appears that the presence of a black councilor decreases the tendency of city officials to target black residents for fines.

Figure 2 – Relationship between racial representation on city councils and fine revenues

One implication of our finding is that the structure of local government institutions should matter in any discussions of police reform, discussions in which the actions of particular individuals and federal legislation have had much more prominence. Our research suggests that institutional reforms at the local government level may also be an important step for reforming criminal justice systems. In particular, the way cities fund themselves and who serves in local governments can have a profound impact on how citizens are treated at the local level. Further, our work raises additional questions that we are pursuing in more recent work: What are the policy consequences of these practices? Do voters who experience fines become politically disengaged? Are police departments distracted from the task of crime prevention by the need to collect revenue? Do police departments and city legislators coordinate revenue strategies? With social scientists taking a renewed interest in the politics and policies of local law enforcement, the answers to these questions hopefully will be found soon.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Who Pays for Government? Descriptive Representation and Exploitative Revenue Sources’ in The Journal of Politics.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2w5CTgW

About the authors

Michael W. Sances – University of Memphis

Michael W. Sances – University of Memphis

Michael W. Sances is assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Memphis. His research interests are democratic representation, accountability, and local government.

Hye Young You – New York University

Hye Young You – New York University

Hye Young You is assistant professor in the Wilf Family Department of Politics at New York University. Her research interests are political economy, special interest groups, lobbying and campaign contributions, and federalism & local government.